Dealing with controversial monuments in Estonia and beyond

23 July 2020Federico Bellentani (PhD 2018) is a digital research manager for a Google Cloud partner based in Italy. His PhD research into controversial monuments has become increasingly relevant due to international protests and calls to remove statues. He discusses his findings from Estonia and his thoughts on dealing with controversial monuments across the globe.

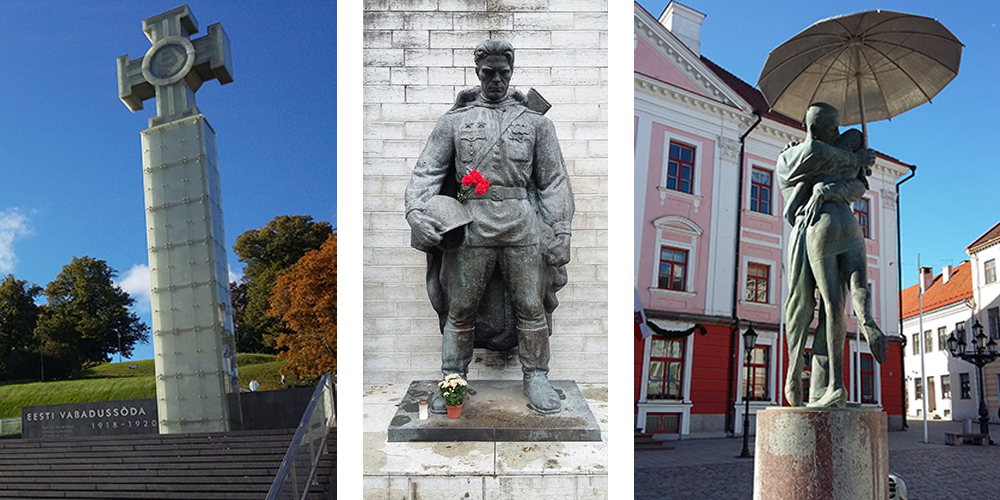

During Federico’s time as a PhD student at Cardiff University, he was looking at monuments and memorials as built forms which communicate certain values and ideas.

“Every day I passed Cardiff’s monuments and statues, especially going into the Glamorgan building with the surrounding war memorials. This environment helped me with my studies.

“Wales is similar to other transitioning countries. Its relationship within the UK has been difficult at times. My case study was Estonia but doing it in Cardiff was meaningful.”

Recently, Welsh councils have been turning their attention to local monuments and memorials and assessing whether to remove them. Federico emphasises the importance of the debate and the complexity of the issue.

His research demonstrates how post-soviet countries have tried different strategies to minimise the impact of monuments by removing, relocating or, in some cases, even hiding them within their surrounding environment.

“I want to be clear – every nation and every statue has its own context. To remove a Soviet monument in Estonia is not the same as removing a Confederate monument in the US. There are very different planning practices and very different ideas of design methodologies.”

Based on his findings, Federico has developed a set of strategies for dealing with monuments, from leaving it as it is and dealing with the material form, to destroying it completely.

“At the state level, I encourage participation with a mix of people – artists, architects, planners, philosophers and everyday citizens. It is important to assess this problem and it’s complex because emotion is very high.”

On the surface, removal of monuments appears to be straight-forward, but Federico explains that sometimes removal can cause unexpected reactions.

“In the Baltics, there have been issues with moving Soviet built forms which for years had been accepted. There’s no tourism around them and they were just functional pieces of the built environment. Still, they were removed by spending a huge amount of money. Often, they were put in a museum where people started to see them. It gave a new life to them.

“Moving them also caused tensions with a controversial neighbour (Putin’s Russia) who wondered why they were being moved. So, in some instances, you can create an intense problem that can lead to economic sanctions, removal of embassies and, at an extreme level, hybrid warfare.”

In this case, removal caused more problems. But, as Federico stresses, every monument or memorial is different.

“Estonia has developed some great ways to include people in the design of monuments. In 2018 they built a memorial to the victims of communism, which is intended to widen public participation through the use of digital tools. Nearby is another Soviet memorial which was not removed, so they live together and coexist.

“It does not erase the past or add tension. The government worked with planners, designers and people who could give a certain kind of solution, resulting in a homogeneous project which, generally, people like.”

Federico is currently working for a Google Cloud partner in Italy specialising in artificial intelligence and collaboration tools. Looking ahead, he is interested in merging his expertise and focusing on digital memorials.

“When you think about memorials, it’s something very material and something you can touch. The current pandemic has shown there can be a commemoration in absentia – when you cannot be physically present to commemorate your beloved. Imagine how many people from across the world in different communities could engage with a memorial if there wasn’t the need to go there physically?”

For more information about Federico’s research, you can read his published papers or his soon-to-be-published book.

- March 2026

- January 2026

- November 2025

- September 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- May 2014