Feedback of/for/as learning: Creating a common way of thinking and talking about feedback

23 August 2023

By Natalie Forde-Leaves, Dr Michael Willett and Andy Lloyd from the Learning and Teaching Academy.

This blog shares highlights from a paper we presented at the International Assessment in Higher Education Conference 2023. The paper focused on the (growing) body of literature, models and paradigms relating to feedback, and proposed a practical approach that both educators and students could use. Our aim of the research was to create and subsequently use and share through our own educational practices, a common vocabulary in assessment and feedback practice. In doing this we adopted some existing classifications applied in the assessment field – these being:

- assessment ‘of’ learning

- assessment ‘for’ learning

- assessment ‘as’ learning

We proposed, and will continue to drive forward, a model of conceptualising feedback that differentiates between ‘feedback of learning, feedback for learning and feedback as learning.

We started our presentation by conceptualising context: as readers may appreciate Cardiff University has a diverse academic landscape with a wealth of research, disciplinary and pedagogic practice expertise, and a growing base of academics undertaking teaching-related professional development activity in the form of the Advance-HE accredited Fellowships Programmes.

However, despite the many pockets of good practice across the institution, Cardiff University has historically adopted a largely ‘traditional’ approach to assessment, similar to many other Russell Group institutions, with an emphasis on ‘assessment of learning’ and many disciplines being “exam-heavy”.

For many years, the NSS results for assessment and feedback have also been well below the mean satisfaction values of all other dimensions.

As a group of senior academic developers with first-hand experience of academic roles, we were mindful of the significant pressures on academic time, particularly the time invested in ‘providing’ feedback, and we sought to understand:

- students’ current perceptions of feedback

- the kind of feedback students desire and expect

- how staff can more effectively communicate feedback expectations and develop students’ feedback literacy.

Winstone et al (2022) address the issue of ‘understanding the term feedback’ in their review of the literature, acknowledging that:

“Feedback is a term used so frequently that it is commonly taken that there is a shared view about what it means. However, in recent years, the notion of feedback as simply the provision of information to students about their work has been substantially challenged and learning-centred views have been articulated.”

Our concerns rest with a ‘shift’ of feedback paradigms, as discussed in the literature from ‘product’ to ‘process’, and whether both staff and students are on the same page in their understanding.

In an extensive review of scholarly discourse we found a multitude of ‘purposes of feedback’, depicted below:

In addition, there are a host of models which, as Lipnevich and Panadero (2021) suggest:

“are proliferating and the field is missing clarity on what feedback models are available and how can they be used for the development of instructional activities, assessments, and interventions”.

This need for clarity is the point of departure for this blog; not only in the feedback literature but also in terms of feedback practice.

In the presentation we agreed with the need to disentangle assessment and feedback (Winstone & Boud, 2022), and argued that ‘feedback’ should be addressed with equal emphasis and parity with assessment and not as an afterthought. As a means of gaining this equity, we proposed conceptualising feedback in the same ways as used for assessment in the literature.

We constructed our common vocabulary, using the notions ‘of’, ‘for’ and ‘as’ (Earl, 2013). This approach is relatively embedded in both assessment literature (see, for example, Chong, 2018) and in practice, see below picture commonly used in our LT Academy workshops:

However, there is little to no use of these terms in the literature in relation to feedback, beyond a single undergraduate thesis (Maldonado and Gafaro, 2014). We therefore propose the following tripartite model as a means of creating a simple, usable, ‘common vocabulary’ for feedback:

Our interpretations:

- FoL: Feedback with the purpose of evaluating student achievement, justifying grades and positioning in relation pre-existing assessment criteria. This feedback is often ‘produced’ by the educator and ‘provided’ to the student in a one-way exchange, characterised by provision of information in relation to an immediate task.

- FfL: Feedback with the purpose of modifying learning and guiding the student as to where they may be able to improve. This feedback is often ‘produced’ by the educator and ‘provided’ to the student in a one-way exchange, but characterised by provision of information and explanations for understanding and improvement in relation to both an immediate task and with applicability to future assessment tasks within the HEI.

- FaL: Feedback with the ultimate purpose of building evaluative judgement, self regulation, metacognition and reflection skills. This feedback is often internal to the student but can also be ‘dialogic’, engaging educators, the student, peers, personal tutors etc in a multi-directional exchange, characterised by new information from alternative perspectives in relation to tasks both within and beyond the reach of higher education

We do not see these three domains as mutually exclusive, but rather as conceptualising the multiple roles and duties that feedback fulfils in various contexts.

We applied our model to an empirical data set with the following Research Questions:

- Can we better understand students’ perceptions of feedback using such a model?

- Using this approach, have student perceptions of feedback changed over time?

The data set comprised secondary qualitative data from a longitudinal mixed-methods study. We analysed student qualitive responses from focus groups held with undergraduate students across a range of disciplines both pre and post covid (2019: n= 5 focus groups (10 participants) and 2022: n= 6 focus groups (46 participants). We also analysed qualitive free text responses from a pre-covid TESTA (‘Transforming the experience of students in assessment survey (n=200)

Informed by our literature review we developed the following coding mechanism to determine whether each data extract showed a perception of feedback as ‘of’, ‘for’, or ‘as’ learning:

| Feedback OF

learning (FoL) to ASSURE: |

Feedback FOR

learning (FfL) to ENABLE: |

Feedback AS

learning (FaL) to BUILD: |

| Correction Confirmation Rating/Scoring Appraisal Information Errors Effort Telling Treatment Costly commodity Command Information Prescription Consumer good |

Diagnosis Raising Achievement Accelerating Achievement Debugging Close the gap Teacher utility Learning Guiding Developing understanding Learner tool Teaching tool |

Motivation & Interest Dialogue & Interaction Connoisseurship Goal orientated Self assessment Dialogue Motivation Ideas Opening up a different perspective Coaching Dialogue Scaffolding Dialogue |

Examples of data coding are shown below. Carl and Dana (all names are anonymised) both provided pre-Covid perspectives of feedback as limited comments on submitted work that did not engage in any dialogic meaningful partnership:

- Carl: “Each paragraph as good. Good, good, good. That’s all the feedback I got was just good. There was no structural feedback, no big comment at the end saying ah you did this well, you could improve by doing this, this is where you went slightly wrong. There was no guidance at all. The feedback was completely useless.” (FoL)

- Dana: The feedback that we get I think is quite, very like ‘you’ and ‘us’ that kind of thing (FoL)

In moving towards feedback of a more formative nature, Amy explained how FfL was provided on a relatively inconsistent basis through the submission of draft work, whereas Dana expressed a desire for more external sources of feedback, and opportunities for students to internalise standards, self-assess and self-regulate their learning:

- Amy: I’ve given one of my lectures a draft before and they read it and gave me comments, which was very valuable, (FfL) but obviously if they’ve got 150 students, they can’t do that.

- it would be good to see other people’s work and maybe how they done something, maybe you could learn from them Maybe if they’re doing slightly better than you, maybe you say, ‘oh wow that’s good’ or like knowing where they are (FaL)

For the post-Covid focus groups we saw focus group comments shifting from perceptions of feedback as ‘Telling to expand but no explanation as to how or giving examples’ (FoL) to ‘What was done well – but what can be done better‘ (FfL) and more idealistically from a dialogic perspective as ‘two way traffic – students and staff talking to each other‘ (FaL).

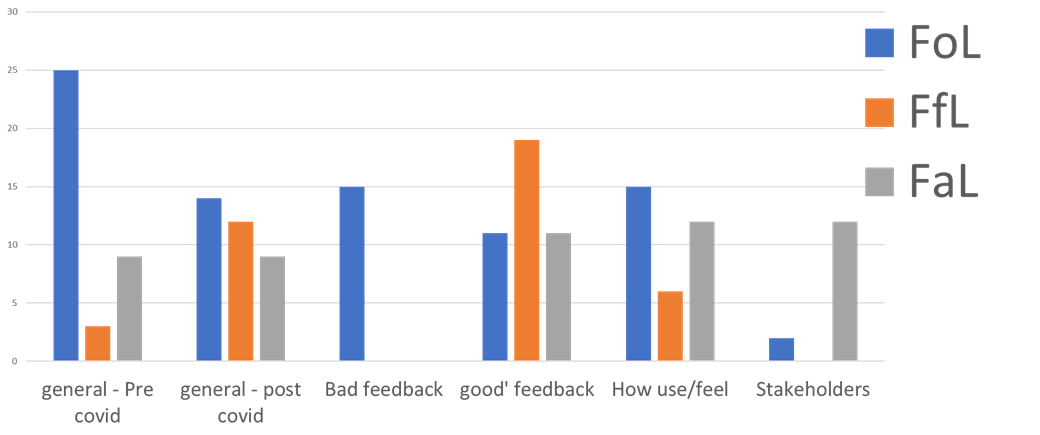

The results are summarised the two charts below. Chart 1 shows how the more negative perceptions of feedback were largely oriented to FoL, whilst more positive perceptions of feedback were in the FfL and FaL domains. Interestingly, the data also shows differences between the pre-Covid and post-Covid groups, shown in Chart 2, with post-Covid perceptions being more orientated to a desire for more FfL and FaL:

This data suggests there will be an enduring problem of ‘talking at cross purposes’ if educators fail to understand which domains of feedback students are expecting and anticipating at various points in their student journey. We suggest feedback literacy can be enhanced if both educators and students acknowledge the three domains of feedback and use these as a way of thinking about and speaking about feedback in educational exchanges.

On reflection and having had some valuable feedback at the International Assessment conference we do acknowledge the limitations of this tripartite model as being relatively simplistic, with room for more detailed conceptualisations of the three terms. At the conference we also discussed the limitations of secondary data with inconsistencies in the number of students and disciplines sampled. To this end, we suggest a more sophisticated longitudinal study utilizing focus groups and questionnaires and a larger sample size.

But overall it was a fantastic experience presenting our work and we are hopefully submitting a paper in October to a journal! If you are interested in using this model with your students or collaborating on this study, please do get in touch!

To cite this blog please use the reference below:

Forde-Leaves, N., Willett, M., Lloyd, A. (2023) Feedback OF/FOR/AS learning: Creating a common way of thinking and talking about feedback? Cardiff University Blog. Available at: https://blogs.cardiff.ac.uk/LTAcademy/2023/08/23/feedback-of-for-as-learning-creating-a-common-way-of-thinking-and-talking-about-feedback/

References:

- BARRAGÁN MALDONADO, C. D. & CONDE GÁFARO, B. L. 2014. First steps towards change an approach to English assessment purposes, types of assessment and washback in the Bachelor of Arts in Modern Languages at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

- CHONG, S. W. 2018. Three paradigms of classroom assessment: Implications for written feedback research. Language Assessment Quarterly, 15, 330-347.

- HOUNSELL, D. 2007. Towards more sustainable feedback to students. Rethinking assessment in higher education. Routledge.

- JENSEN, L. X., BEARMAN, M. & BOUD, D. 2021. Understanding feedback in online learning–A critical review and metaphor analysis. Computers & Education, 173, 104271.

- Lipnevich, A. A. and E. Panadero (2021). “A review of feedback models and theories: Descriptions, definitions, and conclusions.” Frontiers in Education: 481.

- National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. (2017, March 30). Expanding our Understanding of Assessment and Feedback in Irish Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/publication/expanding-our-understanding-of-assessment-and-feedback-in-irish-higher-education/.

- ORRELL, J. 2006. Feedback on learning achievement: rhetoric and reality. Teaching in higher education, 11, 441-456.

- Winstone, N.E. and Boud, D., 2022. The need to disentangle assessment and feedback in higher education. Studies in higher education, 47(3), pp.656-667.

- YU, S., YUAN, K. & WU, P. 2023. Revisiting the conceptualizations of feedback in second language writing: a metaphor analysis approach. Journal of Second Language Writing, 59, 100961.