Services and Standards: Stand Off or Stand Up?

5 February 2019“To understand Toyota’s success, you have to unravel the paradox – you have to see that the rigid specification is the very thing that makes the flexibility and creativity possible”

Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System. Spear and Bowen, 1999.

“The specialisation and standardisation of work …. lead to more handovers, fragmentation of the work, duplication and rework that more than cancel out any gain”.

Lean is a Wicked Disease. How Service Organisations are Waking Up to the Problem. Seddon, 2010.

As a Lean Thinker the world can seem pretty confusing at times! It is our job to both study and learn from the past but also to challenge the now, so that we can improve tomorrow. The previous two quotes highlight the predicament that many of us face. I highly respect the work of Steven Spear, H. Kent Bowen and John Seddon, who have all greatly contributed to my understanding of what it means for an organisation to pursue perfection, but who is right? And why must there be a fight?!

When I work with organisations, I try to help them to make sense of what it means to embrace a continuous improvement approach. Together, through teaching, we discuss what we consider to be the key elements of a lean enterprise and then we try to understand how the different elements interact with each other and mesh together to form a completely new, impressive and dynamic ‘organisational compound’.

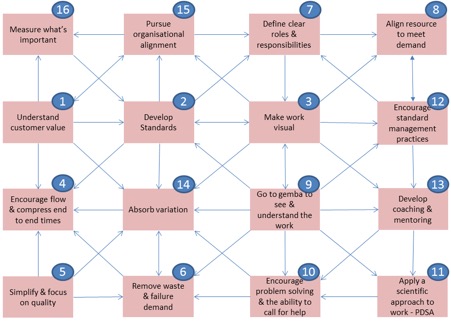

What inevitably happens as part of these discussions is the development of a spiderweb diagram. This map illustrates how all of the different elements feed each other, and evolve from each other and all coexist together. I consider the development of standards to be a critical ingredient within this web.

The diagram above is my attempt to ‘tidy up’ my thoughts in this area. It isn’t perfect, it doesn’t comprise of all of the necessary elements needed within a lean enterprise, but it does help teams to see how many of the key concepts knit together. Arrows indicate some kind of relationship between the different elements. The relationship indicated could suggest that one activity needs to happen before its related entity can exist, or that that element will contribute to the success of its related element. So let’s start to unravel the web, and to extract the role that standards play in the success of a continuous improvement approach.

Obviously, one of the most important focus points for lean is to understand customer value (1) and then to chase after this customer value. I have linked the customer value box directly to the development of standards (2). A standard to me is a kind of agreement between staff, the organisation and their customers about the quality of work that can be expected. Therefore, it makes sense that the standard should encapsulate what customers need, want and expect from the product or service.

But what should the standard look like? Well that’s why I’ve linked the standard box to the important principle of making work visual (3). The best standards are simple, clear and easy to understand (4). They shouldn’t be overly complicated or prevent workers from being able to think. Especially in service.

John Seddon is right to criticise the development of overly specified standards which attempt to turn workers into robots. We have all experienced the pain of being on the receiving end of a call centre script or the inflexibility of a customer service interaction where your reasonable request is quashed by the ‘it’s company policy’ line. What I think is key is to understand the ‘granularity’ of the standard that is required and that different situations will require a different degree of detail.

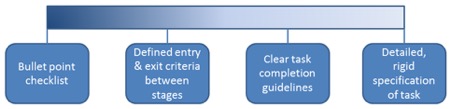

I see the granularity of standards as a kind of spectrum. Where one end of the spectrum is the rigid, detailed specification of miniscule tasks and the other end of the spectrum is just a kind of checklist, to ensure that some of the critical parts of a process have been achieved.

Standardisation Spectrum

So what lies between the two ends of the spectrum? Well, learning about Four Fields Mapping from Dimancescu has helped my understanding about how to flex standards to suit different situations. This project management technique involves agreeing ‘Entry and Exit Criteria’ at each phase of the work activity in question. Work must not move from phase 1 to phase 2 unless all of the exit criteria have been achieved. Phase 2 must not allow the work to ‘enter’ if it has not satisfied all of the essential requirements. These quality gates help to marshal the work safely through the process, in the shortest possible lead time (5).

I believe that using the idea of ‘entry and exit criteria’ as a type of standard can be hugely beneficial when helping to improve processes, particularly in services. Spear and Bowen taught us about how important clear and concise, unambiguous communication is between different sections of an organisation within their 4 Rules of the Toyota Production System and by collectively agreeing what work needs to look like as it moves from different departments, many errors and rework can be averted (6). I think that by developing a collective understanding of what is required by different teams, when it is wanted, helps to define clear roles and responsibilities (7) and can help to better align resource to meet changing demand profiles (8).

Of course, the development of standards goes wrong, regardless of the degree of granularity of standard that is pursued, when they are not truly developed by the people for the people. Standards must be developed where the work happens, at the gemba (9), in order to be relevant and useful. Therefore, it is also these people who will be able to decide the level of detail that is required within the standard (i.e. where the standard needs to fall on the standardisation spectrum). If the standards are developed for the people, by the people, they will also be much more likely to use the standard as a basis for improvement, searching for new ways of working, thanks to the visibility and clarity that a well developed standard can provide.

The fact that standards provide the basis for problem solving (10) and provide organisations with the opportunity to apply a scientific approach to the world of work (11) is very well documented and discussed. When coupled with the guaranteed reflective time and space that standard management practices (12) provide, standards provide leaders with a fantastic opportunity to coach and mentor (13) their staff to reflect on their working practices with a view to improve them.

So if the standards that are developed are simple, active and helpful, they should be able to give employees the clarity and confidence to be able to do as Seddon discusses, to absorb variation (14). The best way to absorb this variation, I think, is to be sympathetic to the plight of the customer who has requested a service from you, or as Seddon advocates, to understand the purpose of why you are there! It is therefore critical for the organisation to be aligned to this understanding (15) and for the standards that are developed to be aligned to this mission.

A standard also provides a great opportunity for an organisation to be able to collect data about how the process is performing as it provides a kind of yardstick to measure against (16). For example, if we aim to deliver a response to a customer request within 24 hours, we can design key quality entry and exit criteria as a type of standard for the process, and then monitor our effectiveness at being able to deliver to this standard. Note, this is not to advocate the use of targets, which we know can cause all sorts of perverse organisational behaviour, but to merely encourage the pursuit of perfection through an increased awareness of how the work is done.

All of these wonderful things can be achieved, as long as you don’t take the concept of developing standards to the nth degree if it’s not necessary, and that’s why understanding where the approach needs to sit on the standardisation spectrum is so important. So I believe that both Seddon and Spear and Bowen are correct to some extent, but that what is required, as ever, is a very sensitive approach to the application of continuous improvement concepts in different environments, particularly within the world of service.

I believe that by better understanding how the different constituent elements of a lean enterprise knit together, change agents can better work with teams to flex the improvement approach needed in order to make a difference. Standards in service must be respected as one of the lean enterprise’s critical keystones however. It’s just essential to be able to adapt the granularity of that standard and to appreciate that a 5 point checklist, if that’s all that’s required in order to increase quality, increase process visibility and therefore customer confidence, is an excellent contribution in terms of helping to achieve improvement.

Sarah Lethbridge, 2012

Lean Management Journal, 1 June 2012 Issue Number: 5

- Lifetime Loyalty and Taylor Swift

- Looking at Things Differently

- Networking Noodles

- Addicted to Truth

- Designs on Service Design

- The Multiple Joys of Universal Design

- Hungry Cultures

- Event Lean

- The Traffic Analogy

- Moving on Up

- Rosé Cava Revolution?

- Powerpoint Sneaky Lean

- Writing about Writing

- ChatGPT Response: Exploring the Art of Expression: Unveiling the Magic of Writing in the Style of Sarah Lethbridge

- Help to Grow Coldplay Style

- Caring IS Everything!

- Institutional Flapping

- “Just Do the Next Right Thing”

- Trust Thermoclines

- Organisational Tempo

- The Inaugural Lethbridge Customer Service Awards

- Vaccine Lean – The Dawn of the Water Spider

- The Queen and Lean

- Decisions, Decisions, Decisions

- Peaceful Protest

- Tesla Tales

- Back to Reality!

- Carrots, Sticks and Buckets of Time Tricks

- The Great Pandemic Pause

- Organisational Therapy

- Late Night Wordleing

- Vaccine Lean

- Chief Letters of Complaint Officer

- AMBAZING Accreditation!

- My Big Lean Head

- [Let us] Help [you] to Grow: Management

- The Love Island Blog

- More Haste, Less Speed

- The Power of Persistence

- Brain Training

- July 2024 (1)

- June 2024 (1)

- May 2024 (1)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (2)

- December 2023 (2)

- October 2023 (2)

- September 2023 (1)

- July 2023 (3)

- June 2023 (1)

- May 2023 (1)

- April 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (1)

- February 2023 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (2)

- August 2022 (2)

- July 2022 (1)

- May 2022 (2)

- April 2022 (1)

- February 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (2)

- November 2021 (1)

- October 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- July 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (2)

- April 2021 (1)

- March 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- October 2020 (3)

- August 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (2)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (2)

- October 2019 (1)

- September 2019 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- February 2019 (3)

- October 2018 (1)

- September 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (10)

- April 2016 (1)

- January 2015 (3)

- July 2014 (9)

- September 2013 (1)