If Innovation is the ‘Next Big Thing’, where does that leave Lean?

5 February 2019

Sarah Lethbridge and Maneesh Kumar

As a lean devotee, it is very easy for me to answer the question “How lean can we go” with “all the way …. naturally!” But as true lean thinkers, it is right that we should constantly review the relevance of lean and try to better understand how the methodology is evolving, recognizing that, in the same way as lean has absorbed elements of other improvement methodologies, lean too will be superseded by a new operations management paradigm.

It appears that innovation, whilst far from a new concept, is now the hotly sought after ‘ingredient’ that organisations are desperate to harness, adopt, nurture and grow. Yet many of us are all aware of the tension that lean can experience with innovation.

Lean vs. Innovation – The Argument ‘Against’

In a previous article for the LMJ in 2012, Services and Standards: Stand Off or Stand Up? I discussed John Seddon’s severe criticism of that cornerstone of lean, standard work – how lean’s obsession with standardization ‘locked in’ processes that didn’t work and that attempts at improvement within these standardized processes merely did the “wrong thing righter”. The article then reminded us that the point of developing a standard was to develop the ‘one best way that we know now’ as a base, and then to use this base as a platform upon which to examine how to incrementally improve. That’s all very well in theory, but practical experience tells us that developing standard work is hard, and once achieved, the tendency to stick to that standard for too long, shying away from any kind of process improvement, can be too great. When coupled with the construction of an IT architecture around the process, change can be very difficult indeed.

There have also been numerous articles such how the introduction of more rigid methodologies such as Lean Six Sigma, suppresses innovation, even at companies that are known for their innovative culture. GE in particular, has been the subject of many reports that suggest that their devotion to the improvement methodology has limited their creativity. When GE’s James McNerney left to join 3M bringing the improvement methodology with him, discussion then turned to the company’s (who, lest we never forget, invented the post-it note) struggle between efficiency and innovative creativity. In a 2007 Bloomberg article of the same name, the author, Brian Hindo discusses how innovation projects “took a back seat” once the methodology was introduced, that 5S “stifles creativity” and “The more you hardwire a company on total quality management, [the more] it is going to hurt breakthrough innovation,” a quote from Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business, Professor Vijay Govindarajan.

There is not doubt about it, practicing lean requires a ‘hardwired’ disciplined approach and whilst innovation requires determination, it is fair to say that to achieve radical innovation a certain amount of freedom is required. In Darius Mehri’s 2006 article “The Darker Side of Lean: An Insider’s Perspective on the Realities of the Toyota Production System” Mehri is very critical of affect that the discipline Toyota Way has on innovation claiming that in fact all of Toyota’s innovation is ‘outsourced’. So, if the freedom to think crazy, ‘out of the box’ ideas, to develop a spirit of experimentation and a desire to learn is necessary to foster innovation, where does that leave Lean?

Lean vs. Innovation – The Argument ‘For’

There are many elements of lean thinking that actually are in keeping with an innovation approach, the most compelling being the inherent scientific nature of lean enquiry. Plan, Do, Check, Act is in itself, a constant pursuit of change and improvement. Lean organisations should assign time and space for employees to stop and reflect on their current work practices and then change them for the better.

Another positive ‘innovative’ element of a lean organization is the desire to work cross-functionally. Dr Joe O’ Mahoney at the Cardiff Business School discusses the need to enable ‘liminal’ or ‘inbetween’ spaces across organizational, departmental, functional or cultural boundaries in order to harness an innovation culture. Enabling these spaces involves not only encouraging key individuals to span company boundaries by also collaborating with customers. Again, close working relationships with customers, a classic lean approach, should trigger innovation as together they solve problems and meet emerging demands

So Who Wins?

As ever, the answer is not as straightforward as lean vs. innovation, we HAVE to consider firstly the different types of innovation and appreciate different gradients of innovation activity.

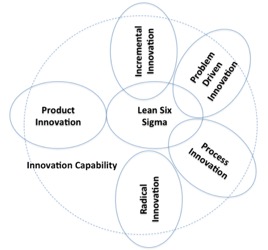

Antony, Setijono and Kumar, in their paper “Lean Six Sigma – Exploratory Research in UK Organisations” discuss 6 different, fairly self explanatory types: Process Innovation, Product Innovation, Incremental Innovation, Innovation Capability, Radical Innovation and Problem Driven Innovation.

They conducted research within 10 companies in order to investigate the impact of Lean Six Sigma on Product or Service Innovation. The majority of respondents stated that Lean Six Sigma fosters innovation, but that it mainly does so in an incremental way. They comment that the methodology “facilitates” innovation through the encouragement of problem solving but that it is not actively involved within the development of new products, or within radical innovation leaps. Indeed, In the 2010 article “Lean Six Sigma, Creativity and Innovation” written by Hoerl and Gardner, both from GE Global research, New York, they agree that Lean Six Sigma is not a path to large scale ‘disruptive’ innovation but that continuous improvement within processes is essential in order to be successful.

Following their research, Antony, Setijono and Kumar have visually expressed how Lean Six Sigma impacts the different types of innovation within the following diagram. Here Lean Six Sigma does not directly influence product innovation or radical innovation, but does directly contribute to incremental, process and process driven innovation. The team also recognize that although it does not directly affect product or radical innovation, these sit within an organisation’s innovation capability and so both do have a role to play in terms of supporting an innovation culture.

Lean Six Sigma and its influence on various types of innovation

Adapted from Antony, Setijono and Kumar

So if lean thinking does not directly encourage large scale innovation now, will it ‘improve’ to better incorporate our understanding of innovation practices in the future? Will a new paradigm of operations management be mainly focused on innovation and merely accommodate some principles of lean? At the Lean Enterprise Research Centre, our approach has always been to challenge the fixation with one particular methodology, and encourage an appreciation of a range of methodologies.

Within the MSC Lean Operations, John Bicheno was always looking at new ideas which could enhance our knowledge of ‘what is lean’. For example, teaching students the basics of the Russian innovation methodology TRIZ, which outlines many different innovation ‘formulae’, or paths, which companies can use to ‘predict’ the next step change in innovation. The knowledge of TRIZ innovation paths can be used to imagine a better, more ‘ideal’ future state.

Future States and Seven Wastes

Whilst a focus on the classic seven wastes has, for a long time now, been criticized within the lean community as ‘too simplistic’ a view of lean, but perhaps, like TRIZ, the wastes themselves can be seen as a pathway to innovation or predictors of innovation if you will.

Consider UK vehicle licensing for example. In 1999, tax discs were issued only in Post Offices and local DVLA offices. In order to process all of the tax discs necessary in the month of August, huge queues would form as car dealers waited in DVLA offices processing the surge of new cars bought to take advantage of September’s new registration plate. The wastes here are: inventory – all of the forms needing to be processed; transportation – car dealers travelling to DVLA offices, motion – dealing with the forms within the office, waiting – in the offices, over-processing – multiple entry in forms and computers and as always, a whole lot of defects when dealing with a lengthy process. Skip forward a few years, and large dealers themselves were allowed to issue tax discs, another new registration month was introduced, reducing inventory and reducing transportation. Another few years pass and individuals could order their tax discs online, skip forward to 2014 and the physical tax disc itself has become redundant, the ‘value’ for the Government lying in the computer database that recognizes the license registration as being taxed or untaxed.

Elimination of wastes towards a more ideal ‘perfect solution’ predicts an innovation pathway, what is perhaps more difficult, is actually creatingthe innovation to enable the leaps and that’s something that organisations can struggle with.

Coping with the Struggle

Dr Joe O’Mahoney from Cardiff Business School states “Most organisations are schizophrenic when it comes to innovation, they love the success of innovation … but on the other hand, they hate the risk, the unpredictable, intangible and ultimately uncontrollable nature of the creative process”. When organisations achieve the balance and become ‘ambidextrous’ – step change, radical innovation, coupled with effective, stable, standardized operations which incrementally improve, their success will know no bounds.

Charles O’Reilly III (Stanford University) and Michael Tushman (Harvard University) in their 2004 Harvard Business Review article, “The Ambidextrous Organization”, acknowledge the “paradox of exploitive vs. explorative efforts” i.e. the dilemma of seeking efficiency and effectiveness within process whilst allowing freedom and creativity to explore new ideas. They suggest that clever companies separate disruptive innovation efforts from continuous improvement, enabling distinct processes, structures, and cultures to exist within the one organisation.

However, it could be said that lean developments such as Eric Ries “Lean Startup” movement are successfully combining both the desire for ‘lean’ and ‘innovation’ within the one methodology. What’s certain is that if we really want to go as far as we can with lean, the need for innovation must be fully respected, supported and incorporated within our understanding of lean and within an organisation’s strategy.

- Lifetime Loyalty and Taylor Swift

- Looking at Things Differently

- Networking Noodles

- Addicted to Truth

- Designs on Service Design

- The Multiple Joys of Universal Design

- Hungry Cultures

- Event Lean

- The Traffic Analogy

- Moving on Up

- Rosé Cava Revolution?

- Powerpoint Sneaky Lean

- Writing about Writing

- ChatGPT Response: Exploring the Art of Expression: Unveiling the Magic of Writing in the Style of Sarah Lethbridge

- Help to Grow Coldplay Style

- Caring IS Everything!

- Institutional Flapping

- “Just Do the Next Right Thing”

- Trust Thermoclines

- Organisational Tempo

- The Inaugural Lethbridge Customer Service Awards

- Vaccine Lean – The Dawn of the Water Spider

- The Queen and Lean

- Decisions, Decisions, Decisions

- Peaceful Protest

- Tesla Tales

- Back to Reality!

- Carrots, Sticks and Buckets of Time Tricks

- The Great Pandemic Pause

- Organisational Therapy

- Late Night Wordleing

- Vaccine Lean

- Chief Letters of Complaint Officer

- AMBAZING Accreditation!

- My Big Lean Head

- [Let us] Help [you] to Grow: Management

- The Love Island Blog

- More Haste, Less Speed

- The Power of Persistence

- Brain Training

- July 2024 (1)

- June 2024 (1)

- May 2024 (1)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (2)

- December 2023 (2)

- October 2023 (2)

- September 2023 (1)

- July 2023 (3)

- June 2023 (1)

- May 2023 (1)

- April 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (1)

- February 2023 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (2)

- August 2022 (2)

- July 2022 (1)

- May 2022 (2)

- April 2022 (1)

- February 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (2)

- November 2021 (1)

- October 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- July 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (2)

- April 2021 (1)

- March 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- October 2020 (3)

- August 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (2)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (2)

- October 2019 (1)

- September 2019 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- February 2019 (3)

- October 2018 (1)

- September 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (10)

- April 2016 (1)

- January 2015 (3)

- July 2014 (9)

- September 2013 (1)