Economies of Scale vs. Economies of Flow

24 October 2018Often when I’m teaching, I find myself skulking amongst the middle ground of contrasting ideas. Sometimes I’m even perilously perched atop of a massive fence dividing two opinions. Sometimes I’m in the middle ground of contrasting ideas, sat on the fence of indecision, whilst rocking back and forth muttering “it depends”.

I think that one of the strengths of a Business School such as ours is that within our teaching and research, we aren’t selling a solution, we present a range of different perspectives, from a position of impartiality, and, through critical evaluation, we enable our students and those we work with, to reach their own conclusions. Within my field of ‘Operations Management’ great spectrums of options exist and as leaders within complex organizational systems, I believe it is imperative to experiment to see which options are best employed when and where.

One of the most tense decisions as a leader, whether we recognize it or not, is deciding where our business needs to be on the spectrum between an ‘Economies of Scale’ or an ‘Economies of Flow’ approach.

Let me explain these two terms further. You are probably very aware of the term ‘Economies of Scale’. I think I even heard of it before I studied Economics A level. This term refers to the “Financial advantages that a company gains when it produces large quantities of products”. When you order in bulk, companies are more likely to offer discounts for example, offering a lower unit cost saving. When you are big enough, you can potentially buy a big machine to do the work for you, it’s probably a large initial outlay, but you are now making things in such quantity that the machine will ‘pay for itself’ soon enough, justifying its purchase. The machine can do the task faster and more often and when you do the math, you can now produce x many widgets at a fraction of the cost. Economies are achieved as you ‘scale up’ production. It could be said that Fordism was built upon this economic force. Workers were paid handsomely for their efforts, within a shorter working day, where they had to master a fraction of a complete task, which they repeated over and over again, generating huge economies of scale. Achieving the lowest unit cost of production is the primary goal. Within markets of huge demand, Economies of Scale are very powerful.

Economies of Flow aren’t nearly as concerned with money as their economies of scale opponent is. Speed is their primary goal. How responsive are we to the customer? How can we deliver something that the customer wants NOW? A helpful way to think about how Economies of Flow manifest themselves is by considering varying delivery charges. When companies are making regular deliveries to their stores, they’ll deliver your item to a store, for free, but you’ll have to go and pick it up. Not in a hurry and happy to wait 3-5 working days – 99p. Standard delivery £2.99, Priority service – one working day £6.99, Delivered within 4 hours by drone?! £45.99 (it will happen).

Pricing deliveries in this way is a mixture of attempting to change customer behaviour yes, but also as a consequence of the effort and actual cost spent in order to speed your delivery up above and beyond ‘usual channels’. Some of this is a fiction of course (second class mail often has to be deliberately delayed within the UK mail system for example), most of it is not. If we need more ‘little and often’ deliveries then we’ll need more people transporting things, which uses more fuel, which is more expensive – the customer needs to pay more if it wants this level of service.

Perhaps Economies of Scale are sounding more appealing at this point? Well again, I’d suggest caution here, particularly as within service organisations, we are often not making physical things, we are delivering ‘intangible’ solutions created through human relationships.

John Seddon talks much about service organisations’ “ability to ‘absorb’ customer demand” – by this he means empowered employees, who possess the autonomy required to respond to customers’ requests, as and when they happen. Teams are multi-skilled and, contrary to the Fordist model where a worker learns a fraction of a total task and repeats it over and over again, they can adapt to customer requirements, applying sense, reason and intellect to the task at hand. Listening, identifying, helping the customer in front of them.

What often happens within centralized services, which again, might be a very good thing (gosh the world looks great from this aerial fence view!) is that standards become King. Work is rejected if it does not fit the brief. Responses are standardized and the ability to flex is greatly reduced. The realities of such factories of work is, if they are insufficiently designed and resourced, queues start to form. What’s worse is that these queues of work develop lives of their own. Employees shift from actually doing the task to managing the backlog. The backlog grows and grows as those within the queue repeat their request, adding a new work task to the mountainous heap (failure demand).

Another problem with centralized systems is the time it takes for work to actually get there. This problem is lessened within paperless processes, but when there are multiple stages of task, involving many ‘handoffs’ and permissions, the end to end delivery time can actually get worse. When coupled with the “centre’s” potential misreading of the customer requirement once it reaches them (because of their remoteness and distance from the initial demand), we can see that centralized solutions are somewhat losing their appeal.

This is perhaps where Economies of Flow have the edge. In the year 2018, customers want their items/service/solutions NOW and they want them to be RIGHT – this paradigm is not going to go anywhere anytime soon. Speed is often THE competitive advantage. It is unlikely that customers will desire a slower response, except if there are significant price savings and advantages to be had.

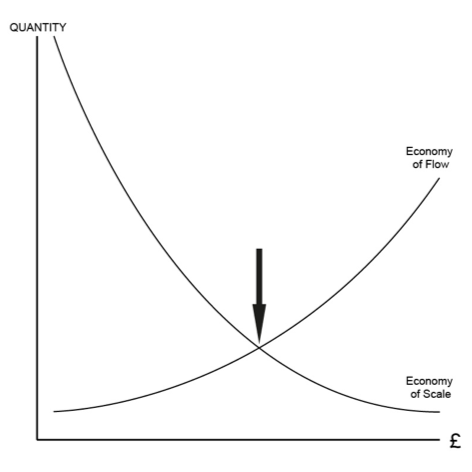

So what’s the answer? Well of course, it depends! Another colleague at Nestlé helped me think through this conundrum with the following graph (Edit update from a flashback: It was Mark Berdusco | LinkedIn again!) We can see here the financial unit cost advantages of an Economies of Scale approach, but also the increasing cost associated with a model focused on speed of delivery. Organisations should seek to find the ‘sweet spot’ of the lowest unit cost Economy of Scale approach and the fastest possible ‘Economy of Flow’ approach. The reality is that this ‘sweet spot’ is much harder to find than the intersection of two theoretical lines on a graph!

I suppose I am going to challenge my own impartiality here and posit that more organisations need to prioritise the Economies of Flow approach as a successful mechanism to 1) win more work 2) secure customer loyalty and 3) deliver fantastic service experience. Localised teams who are multi skilled and are able to flex to meet customer requirement, owning end to end tasks, are desired by customers, and are immensely powerful within service systems.

One final thought – perhaps the graph sweet spot can be achieved through centralized IT systems that work, delivered through localized teams that listen?

Comments

2 comments

Comments are closed.

- Working Smarter and Harder to Overcome Friction

- Mesmerising Mnemonics

- Recharging Batteries

- Marketing Magic

- What’s My Job Again?

- The Reports Have Gone to Her Head

- Cross Stitch Standards and Creativity

- Hefin David and the Aeroplane Arms

- Hankering for a Handbook

- Window of Light

- Defensive Organising

- McMullin’s Tandem of Co-Production

- The Joy of John Parry-Jones

- The Perils of Disappointment

- The Shield of Shame

- Customer Care and Organisation Innovation

- Hooray for Humanity!

- Angry Lemons

- Double Meanings

- Ticketing Masterplans

- When will it all end …

- Lifetime Loyalty and Taylor Swift

- Looking at Things Differently

- Networking Noodles

- Addicted to Truth

- Designs on Service Design

- The Multiple Joys of Universal Design

- Hungry Cultures

- Event Lean

- The Traffic Analogy

- Moving on Up

- Rosé Cava Revolution?

- Powerpoint Sneaky Lean

- Writing about Writing

- ChatGPT Response: Exploring the Art of Expression: Unveiling the Magic of Writing in the Style of Sarah Lethbridge

- Help to Grow Coldplay Style

- Caring IS Everything!

- Institutional Flapping

- “Just Do the Next Right Thing”

- Trust Thermoclines

- February 2026 (2)

- December 2025 (1)

- November 2025 (1)

- October 2025 (2)

- September 2025 (1)

- August 2025 (2)

- July 2025 (1)

- June 2025 (1)

- April 2025 (1)

- March 2025 (2)

- February 2025 (1)

- January 2025 (1)

- December 2024 (1)

- November 2024 (1)

- October 2024 (1)

- September 2024 (1)

- July 2024 (2)

- June 2024 (1)

- May 2024 (1)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (2)

- December 2023 (2)

- October 2023 (2)

- September 2023 (1)

- July 2023 (3)

- June 2023 (1)

- May 2023 (1)

- April 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (1)

- February 2023 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (2)

- August 2022 (2)

- July 2022 (1)

- May 2022 (2)

- April 2022 (1)

- February 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (2)

- November 2021 (1)

- October 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- July 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (2)

- April 2021 (1)

- March 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- October 2020 (3)

- August 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (2)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (2)

- October 2019 (1)

- September 2019 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- February 2019 (3)

- October 2018 (1)

- September 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (10)

- April 2016 (1)

- January 2015 (3)

- July 2014 (9)

- September 2013 (1)

Yes, it’s not as easy as the graph looks! I think it’s often assumed that similar queries or similar processes should be dealt with identically to gain these economies of scale but in fact, the customer needs something immediate and bespoke so would benefit more from economies of flow. There’s not enough Right to Left thinking because we don’t see it from the customer point of view. It is strange to me that 19th century manufacturing ideology still dominates when we think about work.