Addicted to Truth

27 March 2024

I’ve been fortunate to be part of a really interesting Senior Leadership course in Cardiff University that involved completing a behavioural profiling tool to help me ‘map my brain’. I love doing these sorts of things but I know that they can divide opinion. I find them really useful ways to help you think deeply about yourself – what makes you tick and what drives you up the wall. The results might confirm what you suspect, might uncover new things that you hadn’t considered but can see as possibilities, alongside those surprising ‘uncovered’ things which you don’t really recognise in yourself at all. The process of thinking deeply about the extent to which you do, or do not, agree with what is presented before you is always worthwhile, I think.

So I’ve been doing a lot of reflecting on what matters to me, thanks to such tools and some Executive coaching that I’ve been lucky to have, and its very hard for me to reach any other conclusion other than that I have a desperate, insatiable need for THE TRUTH.

As I wrote that, Jack Nicholson popped into my head, suited in full marine smarts, shouting “YOU CAN’T HANDLE THE TRUTH!” which is probably fair on some level, but as I get older, whether I can personally take it or not, I find myself desperately craving it – hunting it down, provoking it and basking in its glory when it engulfs me.

There are a variety of reasons why I might feel this desperate need, many personal, and my Executive Coach is helping me to see how my life experiences have a lot of influence in how my working relationships play out. But, regardless of where this need has originated from, the truth is that my truth dependency is there, resolutely, and it both fuels me and frustrates me in equal measure.

In the last session we had on our leadership programme, the course leader Mark Crabtree shared that the ‘mea culpa’ approach was a powerful way to create cultures of truth, build trust and rapport with teams that are suspicious of you personally, to help you to achieve the change that you are seeking to make.

Mea culpa, which means “through my fault” in Latin, comes from a prayer of confession in the Catholic Church. Said by itself, it’s an exclamation of apology or remorse that is used to mean “It was my fault” or “I apologize.”

I first heard this term from my Dad, who, in the great spirit of ‘men only say sorry under extreme duress’ used to say it when something had gone wrong whilst he was at the helm. Why, a cheeky ‘mea culpa’ with added grin, drawing directly from school boy latin lessons, would cunningly admit responsibility at the same time as providing enough of a separative veil to not have to accept full accountability in the medium of English.

If it’s in latin, its more exotic and not real life.

It was enough though because the crucial element is there – acceptance. Acceptance that things aren’t perfect, that the protagonist knows this, and that they were involved in that imperfection. There’s also an assumed admission that acceptance will in some way, start to pave the way to correction somehow.

Leaders who aren’t afraid to go full mea culpa are such a great way to help to build a foundation of ‘psychological safety’ in organisations. Genuine contrition and ownership of wrong doing is a hugely powerful thing. I try to think whether I am willing to share my faults, frailties and failings with people – I really think I do, because I have this insatiable need for honesty, but I’d be lying if I said I was open about absolutely everything. Does that make me a fraud?

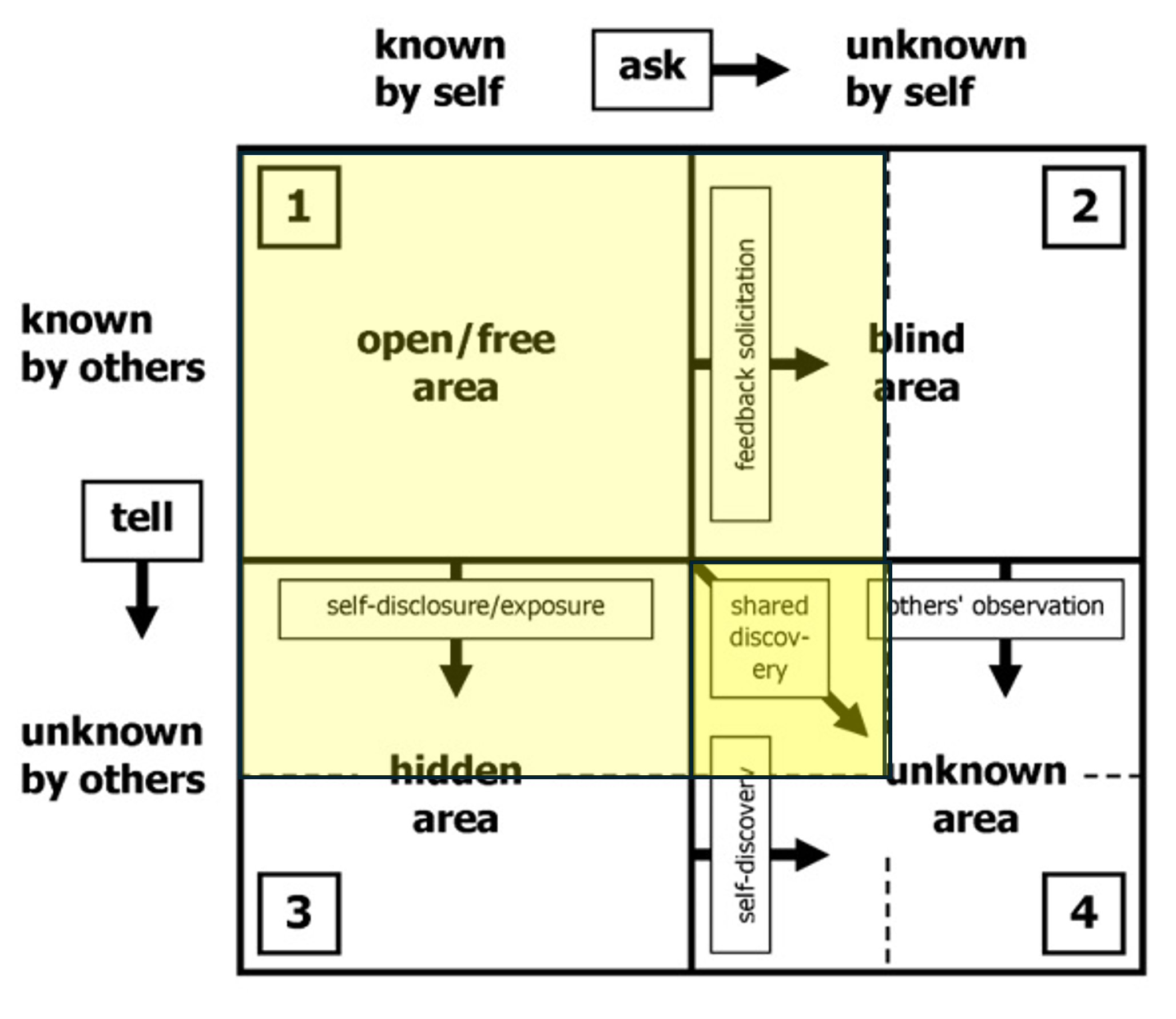

We had another session today with Mark where he reminded us of the Johari window, created in 1955 by psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham. It’s a classic “2 x 2” model, again a useful tool within which you can compare elements of your psyche to try to better understand the way you interact with others, where the top left represents the part of yourself which you know, and others know. The bottom left represents the part that you know, but that others don’t, so there’s an element of hiding aspects of yourself here. The top right is the part of you that others can see, quite clearly, but that you can’t see yourself, and the bottom right of the quadrant is that most elusive of areas – the unencountered part of yourself that you don’t know and that no one else recognizes either.

‘Leave well alone’ you might think, but the point is that not exploring this aspect of yourself means that you are sub-optimally experiencing the world as you won’t have a full grasp of how you move through it.

So I like to think that the size of my Johari arena (shown in yellow) is quite sizeable (arf) because I do ‘self-disclose’, hold my hands up when I have made a mistake, and I do ask people what they think about me, even if I’m not sure I like the results. The slightly darker yellow represents the area of shared discovery as you work together with your teams to unlock new elements about how you tick. But there are things that I have to yet discover and things that others have yet to discover about me and that’s normal and good I think. No-one wants a completely yellow Johari window surely? Urgh how tedious!

As ever, the important thing is not to assume that you have everything sorted, you have to keep reflecting, you have to keep thinking, you have to keep learning and trying to be better.

- Working Smarter and Harder to Overcome Friction

- Mesmerising Mnemonics

- Recharging Batteries

- Marketing Magic

- What’s My Job Again?

- The Reports Have Gone to Her Head

- Cross Stitch Standards and Creativity

- Hefin David and the Aeroplane Arms

- Hankering for a Handbook

- Window of Light

- Defensive Organising

- McMullin’s Tandem of Co-Production

- The Joy of John Parry-Jones

- The Perils of Disappointment

- The Shield of Shame

- Customer Care and Organisation Innovation

- Hooray for Humanity!

- Angry Lemons

- Double Meanings

- Ticketing Masterplans

- When will it all end …

- Lifetime Loyalty and Taylor Swift

- Looking at Things Differently

- Networking Noodles

- Addicted to Truth

- Designs on Service Design

- The Multiple Joys of Universal Design

- Hungry Cultures

- Event Lean

- The Traffic Analogy

- Moving on Up

- Rosé Cava Revolution?

- Powerpoint Sneaky Lean

- Writing about Writing

- ChatGPT Response: Exploring the Art of Expression: Unveiling the Magic of Writing in the Style of Sarah Lethbridge

- Help to Grow Coldplay Style

- Caring IS Everything!

- Institutional Flapping

- “Just Do the Next Right Thing”

- Trust Thermoclines

- February 2026 (2)

- December 2025 (1)

- November 2025 (1)

- October 2025 (2)

- September 2025 (1)

- August 2025 (2)

- July 2025 (1)

- June 2025 (1)

- April 2025 (1)

- March 2025 (2)

- February 2025 (1)

- January 2025 (1)

- December 2024 (1)

- November 2024 (1)

- October 2024 (1)

- September 2024 (1)

- July 2024 (2)

- June 2024 (1)

- May 2024 (1)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (2)

- December 2023 (2)

- October 2023 (2)

- September 2023 (1)

- July 2023 (3)

- June 2023 (1)

- May 2023 (1)

- April 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (1)

- February 2023 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (2)

- August 2022 (2)

- July 2022 (1)

- May 2022 (2)

- April 2022 (1)

- February 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (2)

- November 2021 (1)

- October 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- July 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (2)

- April 2021 (1)

- March 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- October 2020 (3)

- August 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (2)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (2)

- October 2019 (1)

- September 2019 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- February 2019 (3)

- October 2018 (1)

- September 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (10)

- April 2016 (1)

- January 2015 (3)

- July 2014 (9)

- September 2013 (1)