What one Georgian family can teach us about writing letters in the age of Zoom

13 July 2021Rachel Smith, School of English, Communication and Philosophy

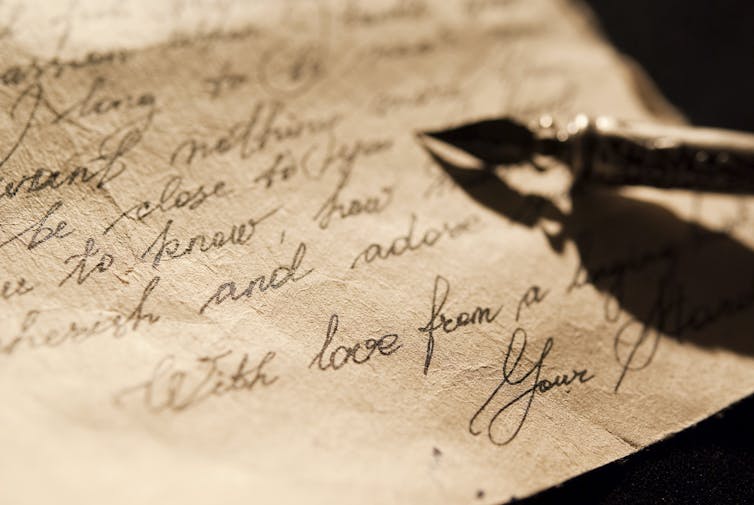

The pandemic has led to a huge increase in how often we use video calls (especially Zoom) to contact family, friends and loved ones across households. However, separation from loved ones is not new. From at least the 18th century, people have been communicating at a distance to maintain relationships. In an age before video calls, texts and social media, showing someone outside your household that you cared meant writing them a letter.

While many have charted the rise of new communications technologies and the decline of letter writing in recent years, my ongoing research examines how people in the 18th and 19th centuries connected. With a focus on one Anglo-Irish family, the Cannings, I’ve considered how people used letters to maintain their emotional relationships at a distance.

The Canning family letters

The Canning archives contain over 1,500 letters from 12 family members from 1760-1830. The most famous member of the family was George Canning, prominent politician and UK prime minister in 1827. The letters evidence the relationships between him and his close family. The volume of correspondence between relatives shows how a network of letter writers communicated and maintained family ties despite being apart.

Hitty Canning, George’s aunt, is one of the main letter writers in the family. An Anglo-Irish widow with five children, she wrote to her teenage daughter Bess whenever she was away from home, often every two days. Full of phrases like “a thousand kisses”, regular updates and affectionate monikers like “my little chick”, the pair’s 1789 letters reveal a number of special moments between them. From jokes written in French (to keep the other readers of these letters in the dark) to advice on behaviour, etiquette and social skills, Hitty and Bess’s correspondence shows that they care about maintaining their intimacy through shared memories and secrets.

However, it was less the contents of these letters but the fact that they were sent regularly that truly maintained relationships. On one occasion in 1789, Hitty even wrote a letter to Bess that started with the fact that she had no news or anything to write about, and yet still filled four sides. Taking the time to write a letter was a sign of affection and commitment to a relationship, an association that has endured, especially with love letters.

Today when someone writes a letter, its rarity makes it an exciting, precious object, a sign of someone’s time and care in composing and posting it rather than simply sending a text. It’s also a lasting reminder, as an object imbibed with emotions, of the relationship that created it. This was the same for familial letters in the 18th century, notwithstanding that they were far more common.

Video calls versus letters

There are actually many similarities between Zoom and letters. Today we complain of “Zoom fatigue”, but letter fatigue was also a concept in the 18th century.

Anyone who has written a letter will know how taxing it can be. Many 18th-century letter writers complained about how many letters they had to write and also how difficult it was to compose a letter within the accepted form and emotional restraints, to ensure proper communication with their recipient.

The Cannings all expressed how tiring letter writing was. Hitty, for example, wrote to her daughter Bess in 1789 saying that she had to “have a holiday” from her pen as she had written so many letters, including one to America. George Canning Sr, George Canning’s father, wrote of his “trial” of writing about his feelings for his paramour Mary Ann Costello in 1767, as he had to write without artifice and flattery but still address the usual conventions of declaring the strength of his feelings and persuading Mary Ann that he was the man for her.

But that’s perhaps why the letter became a symbol of affection, commitment and love. Writing about how hard and time consuming it was to write a letter showed that you cared about your loved ones. George Canning Sr wrote about the difficulties he had in communicating his “love” for Mary Ann in a letter saying: “I have taken up the pen, though much at a loss how to employ it”, and future Prime Minister George Canning wrote with “fear and trembling” as he tried to snatch time to reply to his cousin, Bess, before being interrupted by his morning visitors. All emphasised that they wrote letters for the sake of their loved ones.

Like today’s internet connection issues, technological issues also hampered 18th-century letter writers. Many contain frustrations with pens (quills) and the difficulties in sharpening them for writing. There were also issues with sending letters, which could take anywhere from a day across London to several months for those overseas. Thus, patience was an important virtue and made the resultant letter an even more precious commodity.

While letters aren’t as practical for today’s fast-paced society, they remain a wonderful, nostalgic communication method, full of emotional meaning. If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that every now and then it’s good to slow down and connect with those closest to us. So, consider sending a loved one a handwritten letter to show them that you care. It may just make their day.

- Find out more about Rachel’s work on her research website.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- June 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- Biosciences

- Careers

- Conferences

- Development

- Doctoral Academy Champions

- Doctoral Academy team

- Events

- Facilities

- Funding

- Humanities

- Internships

- Introduction

- Mental Health

- PGR Journeys

- Politics

- Public Engagement

- Research

- Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Staff

- STEM

- Success Stories

- Top tips

- Training

- Uncategorized

- Wellbeing

- Working from home