Hubris as Prime Ministerial Vice

31 July 2017

When Theresa May’s snap election backfired decimating her majority, many commentators were quick to use a language of vices to describe her errors. ‘May’s astounding arrogance has now paved the way for another General Election’, complained the Independent, echoing attacks by the Guardian and Mirror of the various forms of arrogance in the Prime Minister’s conduct. Other vices were invoked, too. ‘An epic tale of hubris’, declared the New Statesman, echoing the Financial Times’ declaration that ‘May’s hubris robs Britain of stability’.

An appeal to vices – negative character traits – was just one dimension of the critical debate concerning May’s conduct and its outcome. But the practice of criticizing an individual or group by charging them with vices is a very common feature of our social and public discourse. It’s a practice that I’ve elsewhere called ‘vice-charging’, and it’s important to understand what is going on when we talk about greedy bankers, dogmatic politicians, and closed-minded pundits. Is talk of May’s arrogance, dogmatism, and hubris just rhetoric – a way of venting frustration or letting off steam – or is it doing genuine critical work?

A robust vice-charge has to have several features, without which it risks being mere rhetoric. For a start, the vice or vices in question have to be defined. It’s not good enough to throw around terms like ‘arrogant’, since it’s not always clear what that is – what, for instance, is the difference between confidence and arrogance? A robust vice charge describes the vice’s components and structure. Next, the critic must provide evidence that the target – the putatively vicious person – actually has that vice. These two points pull together: if I have a robust account of a certain vice, then I can determine whether a person evinces the sorts of attitudes and behaviors characteristic of that vice. A further requirement is that a vice charge must be sensitive to the conditions under which the vicious agent is acting. Is a person’s arrogance in this case due to their character alone, or is it being shaped by the conditions they’re working in? This latter point matters, since so much of our social and epistemic behavior is shaped by contextual factors – like power relations, pressures, structural considerations, and so on.

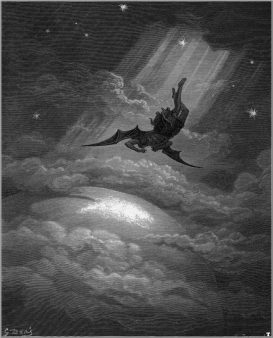

With these points in mind, consider just one of the vices imputed to May – hubris. It’s not a vice that usually springs to mind in the way that ‘arrogance’ does, and is less familiar for that reason. Very roughly, a person is guilty of hubris if they assume or assert their possession of exaggerated abilities or powers – ones that no-one could possess. It’s a sort of advanced arrogance, and leads a person to act in ways that could only be sensible if they did possess such magisterial powers. A famous classical example of hubris is Icarus. Granting to himself the power of flight, he soared higher into the sky, against his father’s advice, acting as if that power was natural – one he could exercise with impunity, despite its dangers, and the result was, of course, his tragic fall to his death. Hubris ends in tragedy. The myth illustrates the dangers of hubris: if a person acts in ways that could only be sensible and legitimate if they possessed rights or powers they lack, then, sooner or later, their hubris will be exposed to their terrible loss.

With this sketch of hubris in mind, are commentators right to charge May with hubris? Giving a comprehensive answer to that question is more than I can do here, so let’s consider just one dimension of hubris – a tendency to act in ways that betray an unwarranted confidence in one’s prospects for success, of the sort we saw in Icarus. Political commentators offer many examples of such hubristic over-confidence on May’s part during the election campaign. The Conservative Party manifesto was derided, by George Osbourne, as the “worst in history”, appallingly heavy on rhetoric and light on detail. The much-derided mantra – ‘strong and stable’ – was undermined by her many U-turns and the conspicuous reliance on highly stage-managed appearances before audiences of Tory loyalists. The introduction of the ‘dementia tax’ social care policy without doing the careful work to prepare the ground through focus groups and internal party committees.

All of this and more was chewed over by commentators, especially the Tories both angry and alarmed at the eradication of their comfortable majority. But all of these behaviors are consistent with hubris. Supreme self-confidence can show itself in a failure to do the work to secure one’s position and power (like campaigning on the back of a strong manifesto or canvassing and engaging with critics as well as cheering supporters). Hubris also manifests as a failure to engage with other people – colleagues, critics, voters – on the assumption that one’s own decisions are steadfast and secure. In May’s case, there is also tragedy, in the loss of her majority and the damage to her personal authority and the surge in support for the Labour Party. All of this is consistent with hubristic character.

The prominence of a language of hubris in the commentaries on May’s conduct surely reflects a sense that there is a such a vice and it manifests in the sorts of behavior she showed during the campaign. But it is one thing to employ a language of hubris – quite another to work this up into what I called a robust vice-charge. A critic who wants to robustly charge May with hubris will need to give a fuller definition of that vice’s psychology and behaviors, and then show she is systematically guilty of them.

Furthermore, the critic will also then have to determine to what extent her hubris is a feature of her character (a vice in the familiar sense) or a feature exacerbated or encouraged by contextual factors. A sense of hubristic overconfidence may be a general feature of a person’s character, but it can be encouraged by contextual factors (like a strong majority in parliament or a history of electoral success or a lack of critical voices urging caution). A really interesting question would then be: to what extent is May’s hubris an artifact of her context – of the advisors she appointments, the internal party culture she has created, and so on. A person can be naturally hubristic, for sure, but they can also be made more hubristic by the conditions they live and work and think in.

Thinking about vicious agents therefore requires us to think carefully about corrupting conditions. Given the familiar criticisms of British political culture – aggressive, brawling, adversarial – reflection on corrupting conditions that encourage vices like hubris in politicians would be very welcome.

To find out more see Ian James Kidd, ‘Charging Others with Epistemic Vice’, The Monist, 2016, 99 (2), pp. 181-97

Image is an illustration of Milton’s Paradise Lost by Gustave Doré which is a public domain work of art

Comments

1 comment

Comments are closed.

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

Hmm it looks like your website ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll

just sum it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog.

I too am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to everything.

Do you have any points for first-time blog writers?

I’d genuinely appreciate it.