Arrogant Pride and Alternative Facts

17 July 2017

Austen characterises it as “a feeling of self-complacency on the score of some quality or other, real or imaginary.” Those who are arrogantly proud, then, are full of themselves and possessed of a feeling of superiority. They dominate conversations, interrupt other people, and are dismissive of views opposed to their own. We are sadly confronted with these behaviours on a daily basis. We observe them among work colleagues; we see them exhibited by those who are meant to represent us in complex political negotiation. We exhibit them ourselves.

Arrogance is an obstacle to rational debate and is particularly pernicious when diplomacy, moderation, flexibility and the ability to compromise are required. There are two features of arrogance in debate that are particularly harmful. When we converse with we acquire obligations toward our interlocutors. For example, everything else being equal, we should avoid lying or misleading them; we owe them to be helpful when helpfulness is not costly to us. In addition, we should be careful with any statement we make. Speakers who make claims, rather than offer mere suggestions or put forward a conjecture, have obligations toward their audiences. They must make themselves answerable and accountable for their claims. They make themselves answerable by being prepared to justify their views in the face of legitimate challenges. They make themselves accountable by acknowledging that they are to blame if it turns out that their claims are mistaken.

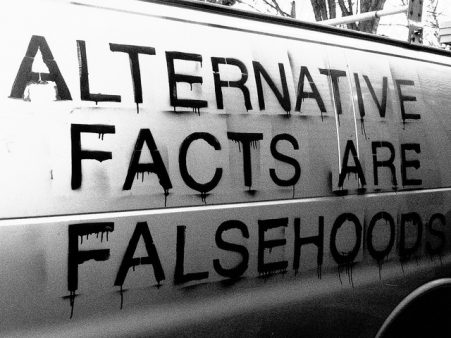

Arrogant individuals in their sense of superiority do not think of themselves as answerable; they respond to challenges with anger and dismissal. Some supremely arrogant people also take themselves to be unaccountable. They behave as if the world should reflect their opinions, rather attempting to adjust their views to reality. They imagine themselves the umpires of what is true, proudly declaring that things are as they call them (but forgetting that they should call them as they are). From here to ‘alternative facts’ the gap is small.

If you would like to read more about arrogance and assertion check out my paper ‘”Calm Down, Dear”: Intellectual Arrogance, Silencing and Ignorance’, Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume 90 (1), 2016, pp. 71-92. You can find a final draft on my website.

Image ‘“Alternate Facts” van‘ by Claire Uziel licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017