Mary Owen: Murderer, mistress, misunderstood?

29 April 2019Elizabeth Howard, School of History, Archaeology & Religion

@LizhiHoward

One of the great rewards of undertaking historical research is finding evidence that challenges previous assumptions. As a historian who works on gender, this is something I often encounter, both while researching and when teaching. My thesis is about women’s experience of crime in Wales c. 1542 to c. 1590 – a topic that is fascinating, if a little gory. One of my favourite cases that I have encountered in my research is the case of Mary Owen, accused of poisoning her husband in 1584. While Mary’s case first appears to fit within a time-worn narrative in which a woman trapped in an unhappy marriage escaped via an administration of poison, further examination reveals a far more complicated story.

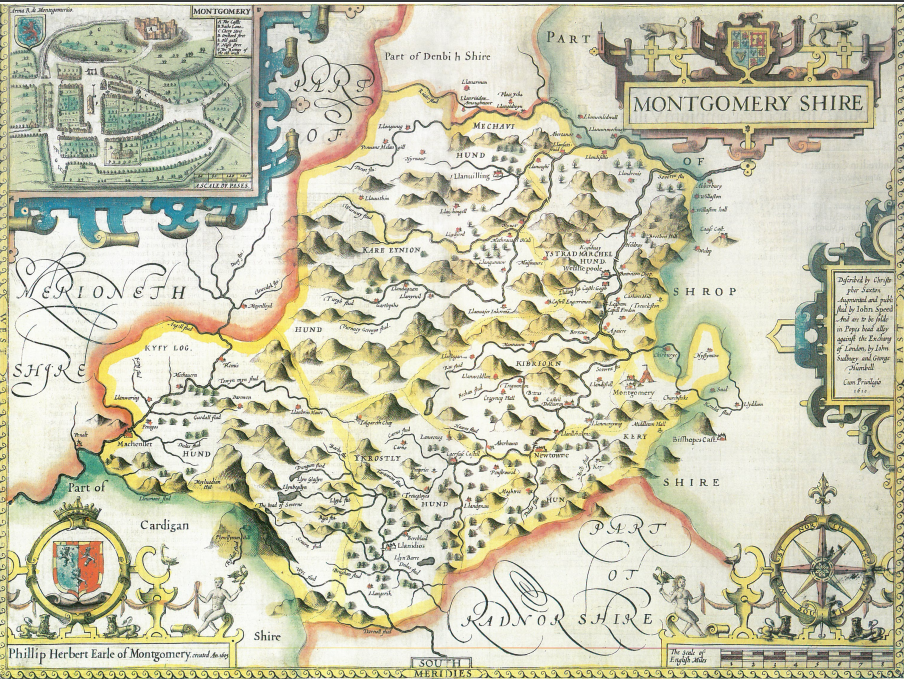

It was Mary’s husband, Owen Thomas ap Edward, who first made the accusation that she had poisoned him. At Machnylleth, Montgomeryshire, on 30 January 1584, Owen, feeling that the end was near, called Richard Morris, esquire and Hugh Pugh, mayor of the town to hear his statement about how he came to this fatal illness. He described how his wife had given him a drink one evening and on his second sip his mouth ‘burned and rose in blisters’. Feeling unwell, Owen went to bed. In the night he continued to suffer and ‘he did so swell that he almost smothered’ or choked.

Asked ‘whether he knew or took it upon his conscious that the drink his wife gave him caused him to languish so long in fear of death’ Owen responded that he did not ‘precisely’ know if it was the drink his wife gave him that caused his lingering death, but he did point out that he had not had his full health since taking the drink. He was also asked ‘what was the cause of his wife poisoning him considering that they had children together’. It is here that Owen made his most damning statement. He alleged that Mary had been having an affair with a man called Evan ap Lewis, the local shoemaker, and he thought that she might want to ‘dispatch’ him so that ‘she could have the said Evan to be her mate’.

Owen’s statement was very timely – the day after he gave it, he died. In a sense, this is a rare case where a victim was able to give a statement about their own murder. The inquest on Owen’s body records that he was indeed killed through poison, although there is no evidence about the condition of his body recorded. There is a deposition from a surgeon called Edward Jones, who said that Owen Thomas had been suffering from a ‘consumption’ caused by poison and that his body was ‘full of hard pimples and his skin in some places [was] hard and pulled and he was very hot and dry within his body.’

Owen and Mary’s servant, Jane ferch Morgan also gave a statement about what had occurred. She described how Mary had forbidden Jane or her son from drinking from the cup she had given her husband. Jane said that Owen had accused his wife of poisoning him as soon as he had become ill, and Mary had denied it. Mary, however, did not behave as an innocent person might – a day or two afterwards she left the house and never returned.

When examined, Mary was upfront about the fact that she did not live happily with her husband. She claimed that he ‘quarrelled’ with her and ‘found fault with every “happy drink” that she brought him’. Her lover, Evan, was also examined. He claimed that there was no plot to kill Mary’s husband; that he never threatened Owen, and never promised to marry Mary if Owen should die. Nevertheless, Mary was indicted twice for Owen’s murder. The second indictment shows the prosecutor as Sir John Thomas, cleric – Owen’s brother. Other witnesses recorded on both indictments include a gentleman and former mayor of the town, and an esquire. These, then, were men of power and social standing.

There were, however, two key pieces of evidence that counted in Mary’s favour. Owen was “poisoned” on 10 March 1582 and died on 31 January 1584 – one year, 10 months, 21 days later. The relationship between Owen falling ill and his death was thus unclear. Further, in the period between the alleged poisoning and Owen’s death, Owen had been well enough to travel to both Bath and Cardiff in order to find a surgeon who would confirm for him that he had been poisoned. These two elements make it appear incredibly unlikely that Mary was responsible for Owen’s death. This was acknowledged by the jury, and they acquitted her.

Interestingly, this evidence shows that a woman accused of poisoning her husband was not automatically assumed to be guilty. Indeed, in my research I have found that in early modern Wales a man who was accused of killing his wife was more likely to be found guilty than a wife of killing her husband. Furthermore, just because a prosecutor was of a higher social standing than the accused did not mean that there was an immediate legal disadvantage. However, we also know that a ‘not guilty’ verdict was not the end of the legal process, and that Mary and her new husband were still burdened by this case many years later – they were still required to appear at each Great Session (the courts in which felonies were prosecuted in Wales) and were threatened with fines if they failed to do so.

Mary does not appear to have been a ‘good woman’ and her case is not the narrative of an oppressed and godly person falsely accused. But it is evident that while we may assume that Mary was significantly disadvantaged, the jury considered the evidence against Mary and found it lacking. Mary was thus found innocent, married her lover, and as far as I can tell after 1589, was never accused of poisoning anyone ever again.

- February 2025

- September 2024

- June 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- Biosciences

- Careers

- Conferences

- Development

- Doctoral Academy Champions

- Doctoral Academy team

- Events

- Facilities

- Funding

- Humanities

- Internships

- Introduction

- Mental Health

- PGR Journeys

- Politics

- Public Engagement

- Research

- Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Staff

- STEM

- Success Stories

- Top tips

- Training

- Uncategorized

- Wellbeing

- Working from home