What does equity look like when we take a broader perspective of Open Science?

4 August 2025

Figure 1 – A summary of the overall pillars of the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science.

In 2021, the 193 member states signed the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science. In this text Open Science was defined as “a set of principles and practices that aim to make scientific research from all fields accessible to everyone for the benefits of scientists and society as a whole”. The UNESCO Recommendation is the latest step in the expansion of the Open Science movement, and significantly outlines a global agenda for opening up knowledge creation through open research practices and infrastructures as well as engagement with civil societies and other knowledge systems (figure 1).

The UNESCO framing of Open Science places equity, inclusion and diversity firmly at the center of the global knowledge agenda. This reflects broader discussions around the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), data sovereignty, epistemic justice and decolonisation. Open Science thus becomes more than a movement to improve the transparency and reproducibility of research, but a way of creating inclusive dialogue and meaning sharing towards the SDGs.

The shift in thinking towards equitable Open Science has been reflected by a growing investment in building open research practices, including funding for training and support, societal engagement and infrastructures. This makes for exciting times, as the ecosystem rapidly transforms how, who and why research is conducted. Nevertheless, it is important not to get swept away by enthusiasm, and to keep a critical eye on how this ecosystem unfolds. In particular, it is important to ask on what infrastructures does this new vision of Open Science rely.

Problems of the “digital divide”

The “digital divide” is a term commonly used to describe the gap between those who have access to and can effectively use information and communication technologies (ICTs), particularly the internet, and those who do not. The term has played a significant role within Open Science discussions, and is used to highlight individuals who are not able to access digital resources online. Using this binary “online/offline” distinction, however, is problematic as it suggests that once individuals are online they are able to meaningfully make use of any open digital resource.

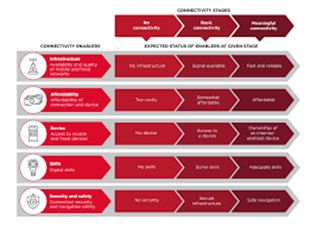

In contrast, however, a growing body of evidence is challenging this assumption. These studies draw attention to the mismatch between the decisions made by infrastructure and tool designers and end users around the world. These include functionality at low bandwidth, type of ICT used to access the site, data burden and many other issues. Instead of thinking about connectivity in terms of online/offline, these studies draw attention to the need to think about meaningful connectivity (figure 2) as key to the success of Open Science. If infrastructures are not designed to accommodate a continuum of connectivity, we will continue to perpetuate global and social marginalisations of knowledge access.

Figure 2. UN framework for meaningful connectivity

Infrastructures have politics

To date, infrastructures supporting the Open Science movement have had highly heterogeneous origins. Some are private companies, some funded by grants, some managed by universities or philanthropic organisations. Furthermore, some are funded by taxpayers, some staffed entirely by volunteers, some operating as commercial companies. This heterogeneity within the Open Science ecosystem is recognised to be challenging in terms of coordination, interoperability and sustainability.

Notwithstanding the heterogeneity in funding, organisation type and governance, one thing that many Open Science infrastructures have in common is their physical location. Indeed, the majority of Open Science infrastructures are registered in a small number of high-income countries – particularly the USA. While it is tempting to think of Open Science infrastructures as digital, and thus “placeless” and “politic-less” recent events in the USA have illustrated, open infrastructures and the data and services they host are far from safe from geopolitical pressures. Indeed, nationally managed infrastructures place Open Science at risk, highlighting the “need to work with community-driven services and university libraries to create new multi-country organizations that are resilient to political interference”.

Hidden costs are hidden barriers

Opening up the products of research – data, papers, software, hardware and educational resources – is key to addressing issues of equity and inclusion. Within academic publishing, for example, the shift from closed to Open Access publishing has removed paywalls blocking reader engagement with academic publications. This transition, while impactful for readers, has a number of recognised challenges. The dominance of gold Open Access models amongst academic journals has meant that “researchers in rich countries now have the privilege to be relatively more visible than colleagues in poor-resource contexts because their institutions can pay expensive fees to publish in Open Access”.

Similarly, the reliance of digital object identifiers (DOIs) as a means of organising digital objects within large databases has led to further complications. Many areas around the world have journals that do not use DOIs, such as Latin America or parts of Asia due to the high costs of DOIs in relation to journal resources. In short, the adoption of some standards which are believed to be universal by the average Western expert is, in practice, very difficult in the contexts of many countries. Recognising that a system or preference that works for one region of the world may not work – in the same way, or at all – for others must challenge uncritical acceptance of infrastructures into the Open Science ecosystem.

Equality of access depends on equity of design

There is a need to transition existing Open Science services and infrastructures to support equity in more meaningful ways. The question then is what are the necessary steps to make that happen? In the first instance there is a need to understand the weaknesses of the present situation and what is inhibiting change. There is also a need to develop a framework to determine how equity, diversity and inclusiveness is implemented from the perspective of Open Science. On the basis of that, outlines for systems that respect that framework can be developed. This will also enable not only thoughtful investments, but also thorough sustainability planning for future infrastructure evolutions.

The UNESCO vision for Open Science is exciting, and sets out an ambitious pathway for the future of global knowledge creation. Nonetheless, the enthusiasm it engenders must also be tempered by caution, as the research structures currently underpinning research are often ill-suited to supporting this new vision. This raises the concern that attempting to graft new approaches to Open Science to old systems may perpetuate marginalisations and undermine the commitments to equity, diversity and inclusiveness unless we learn to prioritise them.

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017