We Should Complain

11 December 2023

I write about complaint to reduce its stigma. I teach classic philosophical texts that argue against it, so I realize the stigma is longstanding. Complaining is soft, Aristotle says. It’s undignified, Immanuel Kant adds. It should never be enjoyed, they both say. I aim to counter that.

I noticed this pattern in the classics while adjusting to moving from the Washington, DC, area to a small city in Ontario. I liked my new home and its good people, but the culture was not quite the same in one way: The negative icebreaker that was a habit on the east coast (“were you delayed by that horrible traffic too?”) was now likely to get the response, “Well, you can’t complain!” And they meant it.

I was probably complaining more than I think.

Most people who hear that I write about complaining immediately tell me of someone they know who complains too much. It’s never themselves, and that might be because it is harder to notice our own excesses. We notice our costs, and complainers cost us. Chronic complaint can result in “mood contagion” for listeners, according to psychologist Robin Kowalski, and that mood contagion can lead to resentment and conflict.

No wonder complaining is assumed to be bad, especially when it seems indulgent, especially when we’re not the ones in pain. Philosophers tend not to identify with those in pain. (As Mariana Alessandri says in Night Vision, “complaining about pain is risky.”)

Protest is different. Scholars are quick to identify with dignified people, and protest asserts dignity, self-respect, respect for others. Protest is productive of change or at least aspires to better worlds. Philosopher Julian Baggini praises protest as one form of “constructive complaining,” and says expressions that fall short of contributing to a better world are “futile,” because “there is no point in protesting that things are not as they ought to be if they can’t be any different.”

His view is like that of many Stoics who encourage focus on what we can control. Whining about what’s not up to us won’t solve anything. I complain about the weather. I have no aspirations to change it. I just want someone to agree that winter in Ontario is too long! Stoics are right. That complaint isn’t productive.

But there is more to life than productivity. Believing that complaint must be either a protest (and therefore good) or it’s pointless (bad) misses out on complaining’s other functions. A complaint can also be a criticism, a greeting, an accusation of blame, an excuse, a release of pent-up feeling, an invitation to another to share in kind, or a plea for sympathy. Sometimes it really is just a report. “Patient complains of …” “I got coffee on my shirt.” We also want to articulate experiences, put words to feelings, sort something out. These are not all equally bad things.

To reduce the stigma of complaint, I encourage identifying with complainers instead of with productivity machines. We are vulnerable to pain and attuned to social situations. At times, we may even owe it to ourselves to complain so that we’re not neglecting our need for help. We need help when we feel terribly isolated. During the pandemic, that isolation was widely experienced. People also reported feeling burned out, especially in care-providing jobs. Burnout is not always responsive to troubleshooting solutions or trying to be more productive. Sometimes complaining is the only thing left to do. Without some affirmation, we can be awfully lost, and at such times it is important to learn that we are not alone.

We can also complain to avoid lying to ourselves or others. To know ourselves, and to be able to tell a coherent narrative about who we are, we have to be honest about our pains. Letting people know that we are not perfect, that we suffer from troubles that others may be suffering from as well, can indicate a healthy self-awareness and demonstrate humility and truth in self-representation. It may take personal courage to admit that we are in pain or vulnerable, but it is important to our own well-being.

Complaining can be done for the sake of others, too. Offering a complaint to another is like opening a door, inviting someone to enter this safe space of disclosure. Complaint seeks acknowledgement (“Surely I am not alone?”) and acknowledges others (“You are not alone”). Even minor complaints can affirm the perceptions of others.

And it’s not always minor. Complaining can be the respite of those with great pain, burdensome secrets, and few avenues for companionable support. In very bad times when it seems like all hope is lost—and it really might be lost, I’m no optimist—then complaining may even be the alternative to despair, or rather, an activity that relieves its weight because the despair is shared. When we want to complain that the unfixable world is hard to bear, making the world better is not the aim.

Of course, complaining might result in personal or social change. Finding that others share or appreciate the seriousness of one’s complaints, even about hopeless situations, can create forms of solidarity that lead to what philosopher Katie Stockdale calls collective hope. Knowing that others see how irreversibly bad some situations are can repair our attitudes toward each other even if it cannot repair the world. And sometimes, happily, we turn out to be wrong. Pointless complaining can lead to unexpected realizations of solutions or strategies for coping that we did not anticipate when we turned to our supporters. That we can be wrong about what’s hopeless should be a compelling reason to waste some time.

I mentioned philosophers who shake their heads at those who enjoy complaining, but complaint is a thoroughly human pleasure that I think my favorite philosopher might have appreciated. John Stuart Mill wrote that we are capable of higher and lower pleasures, and he didn’t just mean mental versus physical. Lower pleasures are simple, direct, unmediated. A lower pleasure can be a grain of sugar on the tongue or a laugh at a joke, an uninterrupted response to perception. A higher pleasure is indirect. Climbing a mountain or reading a mystery is a higher pleasure, painful or confusing in the short term but gratifying over time when we enjoy its complex achievement.

Mill’s point about higher pleasures is that people seek them out. Most of us are complicated beings who don’t merely want grains of sugar on our tongues (although I want those too). It is a common human experience that we cannot help but pursue complex as well as simple pleasures, higher and lower pleasures, and are happiest with a variety of them over time.

Complaining engages our robust capacities for pleasure. We are capable of complex and high-minded pleasures like protest or constructive complaint. But we’re also great at lower and higher pleasures including laughter, mourning, bonding, fighting, trashing, gossiping, and deploring, sometimes all at once. Some complaints are simple yelps of pain. Others are complex forms of social bonding, they pay out over time, and they feel good when done well. I suggest that we should do all of that, together, more often than never.

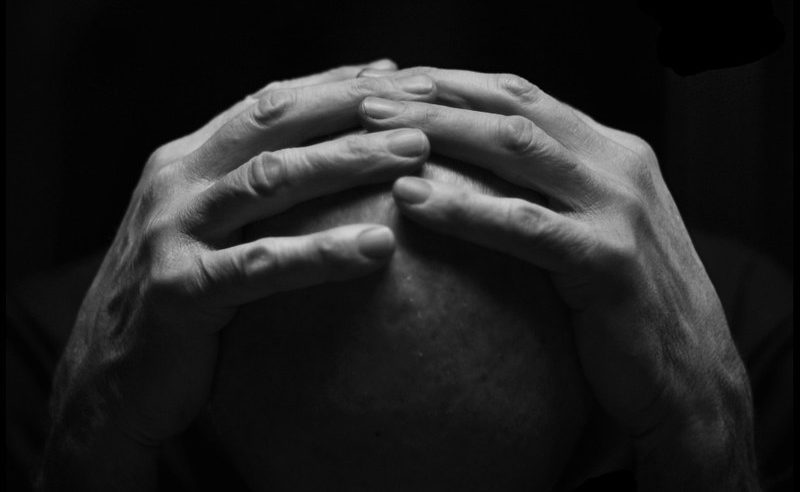

Picture: Hands and Head by Timothy Actwell on Flickr

Comments

1 comment

Comments are closed.

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

I LOVE this. It is so beautifully written. Thank you!!