Sharing bullshit on social media

2 May 2022

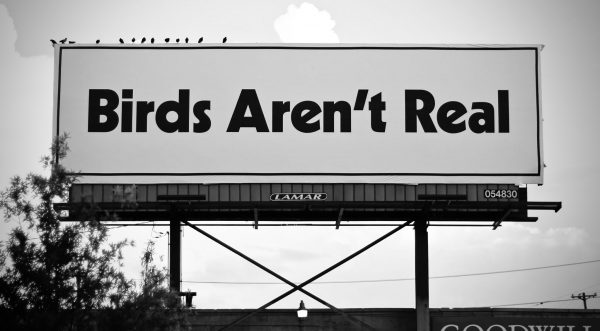

It’s another dull day of commuting to work, and you are waiting for the bus. Bored, you open your phone and start scrolling the all-too-familiar, endless cascade of mildly uninteresting content posted by your friends on social media. And there it is, next to pictures of happy babies and pixelated dogs. A tik-tok video revealing that the Roman Empire never existed. Montagnier’s latest anti-vax rants. Proof that eating pollen is the ultimate anti-aging cure and that birds aren’t real. Loads of bullshit.

Why are social media so ripe with misinformation? Researchers have identified a number of potential culprits. Some point their finger to echo-chambers. Others, to badly-designed algorithms that feed us inflammatory content, rather than filtering it out. The truth is, the causes are numerous and complex. But between the many factors that play a role in this misinformation epidemic, there is one that has not received much press, despite the clear role it plays in the disinformation epidemic: the very existence of a ‘repost’ function on most social media platforms.

The role that reposting plays in spreading misinformation may seem obvious. Reposts are the fuel without which content cannot go viral. In itself, some internet dude’s rant about the latest conspiracy theory can only reach a limited audience– as such, it’s relatively inert and harmless. Not so much when other users start propagating it by reposting it. Reposts increase visibility, calling for other potential reposts, in ‘cascades’ that can reach millions of users.

“Reposting cascades” surely play a key role in the spread of misinformation online, but this mechanism alone cannot explain why false rumours thrive on social media. Reposts can help any content reach wider audience. They can magnify someone’s voice, but they do it regardless of whether they are telling the truth or spreading lies. If we want to explain why more false content is accessible on social media (and not simply why more content is available) we are still missing a piece of the puzzle. The answer resides in how reposts reshape the repertoire of communicative acts that we perform, altering the landscape in which online communication happens.

Rumours and reposts

Reposting is different from most other forms of communication. To understand what makes it particularly apt to spread misinformation, it can be useful to compare it to rumour-mongering. Both are by definition ‘second-hand’ reports. If you insincerely tell me that Lucy from accounting is dating Lucas, the hot guy from sales, you are simply lying. But if you tell me that you’ve heard that Lucy is dating Lucas, you are starting a rumour. A rumour, like a repost, involves communicating that someone else has (supposedly) said something.

When you are caught lying, you pay a toll: your reputation is stained, your credibility is damaged, and your friendship with the dupe might be in trouble. Rumour-mongering avoids (or at least reduces) some of these costs. If you are caught red-handed (Lucy is not dating anyone at the moment), you can always point out that you are not the one who claimed that Lucy is dating Lucas. All you said, after all, is that you have heard that Lucy was dating Lucas – it’s not your fault (you may argue, maliciously) if you got things wrong.

Spreading gossip via rumours is advantageous precisely because you remain able to deflect accusations in this way, avoiding (or at least containing) the costs associated with spreading falsehoods and unverified claims. Donald Trump is a known abuser of this sneaky method: expressions like “a lot of people are saying” or “some people think” were ever-present in his political speeches. They were obvious smokescreens, from behind which the former president would spout his favourite conspiracy theories and lies, while refusing to own to their authorship.

The problem about reposting

The problem with reposting is that it also comes with limited accountability. When you repost someone else’s content, you don’t really vouch for it yourself, taking responsibility for its truth. As the popular disclaimer has established ad nauseam, a retweet is not an ‘endorsement’. Like a rumour, it is a sort of second-hand report. It directs attention towards content that someone else has posted (and taken responsibility for). Linguists and philosophers have likened it to the act of pointing towards something, or quoting what someone has said. It is the social media equivalent to indicating in some direction and saying “hey, check this out!”.

Like a rumour, a repost can help spread misinformation, while avoiding the cost traditionally associated with spreading falsehoods. If you are caught reposting fake news, it’s not as bad as being caught lying. You can always make a case that all you did was sharing the article (“don’t shoot the messenger, right?”), but you did not mean to vouch for its truth.

Trump, once again, illustrates this pattern egregiously. He has frequently retweeted conspiracy theories, fake news and blatantly false claims. Confronted publicly about his retweets, he’s always brushed off the accusations with confidence. For instance, questioned about a retweet alleging that Marco Rubio was not eligible to run for president, he blurted: “Honestly, I’ve never looked at it. Somebody said he’s not. And I retweeted it. I have 14 million people between Twitter and Facebook and Instagram, and I retweet things and we start dialogue and it’s very interesting.”. Similarly, challenged to explain why he retweeted a message from a neo-Nazi account (containing made-up crime statistics regarding white people murdered by Afro-Americans): “Bill, am I gonna check every statistic? All it was is a retweet. It wasn’t from me.”

Retweeting allows us to send messages while distancing ourselves from the content we convey. Of course, the veil between us and the message may be thin. It is fairly obvious that Trump meant to present those retweets as conveying reliable information. Still, had he made those false statements himself (instead of retweeting them), he couldn’t have brushed off criticisms so easily. Like the rumour-mongerer, the retweeter who shares false information still faces a loss in credibility, but this loss is cushioned by a convenient layer of plausible deniability. This limited accountability (and not merely its capacity to make content go viral) is what makes reposting an ideal conduit for misinformation.

Lies travel faster than truth

Here’s another concerning difference between rumours and reposts. In real-life conversations, spreading a rumour requires cognitive and material efforts. Explaining to your colleagues how a group of Satanistic, cannibalistic pedophiles controls the world is a complex task, and requires quite a lot of time – it’s an effort for both the speaker and the listener. These efforts are often enough of a deterrent to stop our conspiratorial friends from sharing their stories in public – before their second pint, at least. Since humans have limited cognitive abilities and limited time, rumours can only travel so far and so quickly.

On social media, these limits were removed the day the repost button was introduced. The navigated liar can now shoot for the stars. Social media platforms are designed in a way that makes reposting ridiculously fast and efficient. Reposting a Qanon conspiracy theory or sharing a link to OpenVAERS takes a single click; it’s instantaneous. Unlike retelling the story yourself, it requires no cognitive or material effort. Because they are so cheap to produce, reposts can create cascades that can reach millions of people in few minutes. Reposts are rumours on steroids.

Crucially, the ease with which reposting can be done (and the limited accountability associated with it) also affects the choices that people make when they communicate online. Why go through the trouble of carefully redacting your own post, risking the disappointment of not reaping any likes, when you can simply click on what someone else has said? Social media create an environment in which reposting is a more alluring option than saying something yourself. According to a study, retweets accounted for over 25% of the material posted on Twitter in 2014, and the number had been steadily growing since 2009, when native retweets where introduced.

In real-life conversations, most of what is communicated is conceived, stated and ‘owned’ by the speaker. On social media, a substantial portion of what is communicated is a second-hand report instead, for which the speaker is only partially accountable. The prevalence of reported speech creates an environment where the disincentives for sharing falsehoods are dramatically reduced. Malevolent communicators can take advantage of this. And clumsy communicators (those who are likely to accidentally communicate falsehoods) are not kept in check by the usual disincentives. The result is sadly known: misinformation reigns.

What can we do to fix social media? Sadly, there is no easy recipe for success. Each social media platform is different, and many complex factors have to be taken into account to design efficient countermeasures. Still, if a simple moral can be drawn here, it’s that we stand to gain from policies that increase the costs associated with reposting. We need disincentives: measures that dissuade users from reposting quickly, light-heartedly, and without facing consequences.

Can this happen? Some software engineers at Twitter have recently moved in this direction. They made quote-tweets the default option for retweeting, increasing the costs of producing simple retweets. They introduced a “pop-up window of shame”, prompting users to read the news they tried to retweet (if they haven’t done it), dissuading them from reposting light-heartedly, and actively prompting them to verify the reliability of what they repost. Of course, these solutions can only lead so far. But small, incremental changes can be a first step towards addressing the misinformation epidemic. Social media aren’t simply going away; but if we play our card just right, maybe there will be less bullshit on our phone, the next time we check it.

Picture: “Birds aren’t real” billboard in Memphis (with real birds); source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%22Birds_Aren%27t_Real%22_billboard_in_Memphis.jpg

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017