‘Implicit Bias’ in public discourse

7 May 2018

The news has been awash with discussion of implicit bias, and the role it seems to have played in the discriminatory treatment of two black men in a Philadelphia branch of Starbucks in the US. Donte Robinson and Rashon Nelson were waiting to meet a friend when they were asked to leave; when they declined to do so, the manager called the police. The incident is one of a pattern whereby black people are denied the right to enjoy spaces the way white people are, namely, safely and without harassment or undue suspicion or threat of (potentially grave) violence (another recent incident that received less coverage than the Starbucks case is the police violence against Chikesia Clemons).

Whilst the case has generated much discussion about implicit racial bias – not least because of the Starbucks CEO’s hasty announcement that all of its employees would undergo bias training in an attempt to mitigate the risks of such wrongs being perpetrated in future – various questions have also been raised.

Was this really a case of implicit bias, rather than explicit prejudice? Doesn’t calling it implicit bias let those involved (the manager, the police) off the hook? And isn’t the move to engage in bias training just a PR move to repair Starbucks’ public image, rather than to seriously address racial bias and prejudice?

There is something to be said regarding each of these concerns. First, why think this was a case of implicit bias, rather than explicit anti-black prejudice? In my view, we don’t have to choose – it can be both. I’ve argued [here (with Dr Joseph Sweetman), here,and here] that implicit biases include a jumble of cognitive processes, characterised by their automatic and fast operation which makes them difficult (but not impossible!) to control or detect. These automatic processes can be present in many of our actions. For example, that the manager undertook a deliberate act (e.g. calling the police) doesn’t mean that implicit bias wasn’t involved – automatic stereotypes could have been active upstream, informing the misperception of the men as suspicious or threatening or unruly. Moreover, even if explicitly prejudicial beliefs were held by the manager – suppose that she explicitly endorsed racist beliefs such as that those men were more likely to be troublemakers due to their race – implicit biases may still have had a role alongside explicit prejudice. For example, automatic fear responses triggered by racist beliefs may have caused her to act rashly, rather than engage in calm conversation with the two customers of her establishment. So in short, we don’t have to choose whether to explain the action in terms of implicit or explicit biases – sometimes (often?) both will be at work.

But doesn’t giving implicit bias a role in explaining discriminatory action have problematic consequences in letting people off the hook? If implicit bias is at work, do we have to say the manager isn’t responsible? In my view, this is also a mistaken inference. People may tend to think that if biases are implicit, or unconscious, then we cannot be held responsible for them. I’ve argued that this is wrong. We can be held responsible for actions based on mental states that we are unaware of. To use a flippant but familiar example – when I forget a dear friend’s birthday, I am unaware of certain beliefs (about it being their birthday) – but this lack of awareness doesn’t make me less blameworthy for forgetting, unless there are mitigating circumstances (extreme stress, distraction by a serious and unexpected event). Mere lack of awareness does not excuse.

But moreover, not being aware of mental states that may lead us to act in discriminatory ways doesn’t mean we’re not responsible. If we should be aware of this possibility, then lacking awareness of it itself can be blameworthy as well.

Why think that we should be aware of such biases and the attendant possibility of being implicated in discrimination? Whilst the notion of implicit bias is gaining traction, not least due its presence in media discussions of such cases, the terminology emerged from the field of empirical psychology, and perhaps many people can’t be expected to be aware of this field of research?

This may be a legitimate concern if the empirical research were the only source of evidence we may have regarding the likelihood of forming discriminatory perceptions and beliefs, or perpetrating discriminatory actions unintentionally or without realising it. But it isn’t the only source of evidence we have. The idea that people can be racist unintentionally, or without realising it is nothing new, and has been pointed out by many writers and scholars – James Baldwin, Gloria Yamato, Patricia Hill Collins, Charles Mills, Claudia Rankine, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, to name just a few. Whilst the findings from empirical psychology provide us with a useful notion to coin the mechanisms that might be at work here – implicit biases – such evidence from empirical psychology isn’t needed to make the inference that people can be perpetrators of discrimination, unintentionally and without realising it. (How we might integrate these different sources of evidence is something that I’m currently thinking about with Kathy Puddifoot)

Finally, what about the move, on the part of the Starbucks CEO to introduce a day of bias training for all employees? Recently, this intention has been revised to include a more long-term series of training. That revision is salutary – the worry that one-off bias training is a ‘tick box’ exercise is a legitimate one. Recent studies about the effects of such bias training in the UK show that such sessions have almost no impact on stereotypes or prejudices that participants may hold – and this is not surprising, since no research shows that merely learning about bias for an hour or even a day suffices to reduce or eliminate biases. Moreover, a recent meta-analysis of attempts to change biases and behaviour suggested that changing biases doesn’t correlate with changing behaviour. This casts doubt on whether bias reduction is where the primary focus should be. Rather, more imaginative changes to institutional practice, and policy, and social context look like better bets for moving towards goals of inclusion and equality than simply focusing on bias reduction. For example, ‘Nelson and Robinson said they’re looking for more lasting results and are in mediation proceedings with Starbucks to implement changes, including the posting in stores of a customer bill of rights; the adoption of new policies regarding customer ejections, racial profiling and racial discrimination; and independent investigations of complaints of profiling or discrimination from customers and employees.’

If bias training is to be effective, a focus on motivating institutional changes, such as those described above, rather than mere bias reduction, should be the focus.

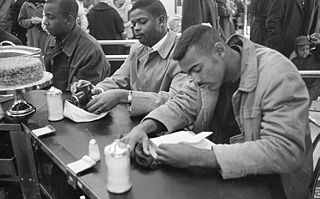

Featured Image: Civil Rights protesters and Woolworth’s Sit-In, Durham, NC, 10 February 1960. From the N&O Negative Collection, State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh, NC. License Confirmed using Flickr API. https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/24495308926/

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017