Being pluralistic about philosophical pessimism (Part 2)

31 March 2025

In part one, I argued that the conceptual core of pessimism is the twin judgments that the human condition is very bad and likely to remain so. However, this does not deliver a full philosophical doctrine of pessimism.

Content and context.

A philosophical pessimist takes these judgements and tries to support them with arguments and rich detail. It’s easy to announce – as people do on Reddit – ‘existence sucks’ and ‘life is a broken product’. It is harder to explain such claims and make them philosophically compelling. Pessimists can therefore become philosophical and in the process develop doctrines of pessimism. Famous ones include the Buddha’s and Schopenhauer’s or the anti-natalist ones defended by contemporary pessimists such as David Benatar. I think the best doctrines of pessimism need to do three things.

The first is to provide content for the pessimistic claims. What are these bad-making features of human life? In what sense are they entrenched? How are they ‘destructive of, or antagonistic to’ deep human goods – and what are those goods? Looking across different pessimisms, the content is diverse and includes the following four:

- Mortality and the inseparability from human life of illness, aging, death and dying and the grief, sadness and fragility that goes with them. These inscribe into human life contingency, painful vulnerability, and a fragility whose existential impact is pithily captured in the title of one moving philosophical reflection on mortality – ‘life is hard’. Recall the Buddha’s ‘origin story’ and his encounters with the three ‘divine messengers’ – an aged man, a sick man, and a corpse.

- Meaninglessness of human life: the alleged lack of purpose or meaning of human endeavours, if appraised sub specie aeternitatis or when seriously scrutinised for their grounds. Think of Camus’s insistence on the ‘absurdity’ of our striving so earnestly to achieve goals which (he says) lack objective foundation.

- Miseries, the panoply of anxieties, disappointments, frustrations, failed projects, unrequited loves, regrets, guilt, and other bad-making phenomena that make us, in Benatar’s term, infortunati. Physical, psychological, interpersonal, and existential distress are the lot of humans. While the exact distribution and intensity of miseries vary, often unjustly, no one could seriously aspire to live a life unblemished by them.

- Misanthropy as acute condemnation of the collective moral condition and performance of humankind. A misanthrope sees human life as infested with entrenched moral vices and failings. Arrogance, cruelty, exploitativeness, greed, hatred, indifference to suffering, hubris and other failings are inseparable from human life as it has come to be.

These four Ms – mortality, meaninglessness, miseries, and misanthropy – are not exhaustive. Others could be added. Perhaps one thinks human beings are deformed or twisted, as Christian doctrines of original sin insist. Perhaps reality itself is in some deep sense hostile to human flourishing.

What matters for our purposes is the diversity of content of pessimistic doctrines. Preferences vary historically and culturally. As several excellent books have shown, recent European pessimists focus on the meaning of life in a ‘disenchanted’ world after the ‘death of God’. But these are specific to recent European cultures. Other pessimists – from the Buddha to Leopardi to Cioran – focus on life’s deep miseries, reporting no theological and teleological anxieties. Many pessimists are misanthropes and relate the badness of our condition to the power and persistence of our moral failings. Yet others – like Benatar – invoke all four Ms.

A second thing supplied by a doctrine of pessimism will be a contextualisation of their content. What narrative does the pessimist offer for thinking about the badness of human life? Some are particularists who describe the bad-making features of life in terms of features particular to their own culture. European pessimists appeal to the ‘death of God’, collapse of Christendom, or the emergence of oppressive technological modernity. Such particularist narratives have their uses and their grandeurs seems to animate people. But grand historical narratives often buy their drama at the cost of their detail. More problematically, they don’t provide us with characterisations of human life—only of particular forms of human life. To counteract that worry, the pessimist could also be a perennialist – explaining the badness of our condition in terms of permanent features of human life, not ones particular to certain cultural histories. Metaphysically complex stories are popular – Schopenhauer’s doctrine of the ‘cosmic will’, for instance. Others tell anthropological stories about the structural imperfections of human nature, or offer existential analyses of Dasein, the ‘mode of being’ of creatures, like us, disposed to ‘inauthenticity’ and kinds of inveterate existential anxiety.

In practice most philosophical pessimists combine both particularism and perennialism. Some succeed in developing doctrines describing perennial aspects of human life as experienced, as one commentator helpfully puts it, within ‘historically specific configurations of human life’. Mortality, for instance, is a universal feature of human life: we are ‘creatures of a day’ destined to decay and die. But the badness of mortality will depend on, among other things, the extent to which one’s culture is ageist, pathophobic, and unempathetic.

Good doctrines of pessimism have content and context and offer argumentation and evidence, and sometimes also include metaphysical, cultural, and historical material, too. Such content only describes the human condition, though. The last desideratum for a good doctrine is guidance.

The conduct of life.

Philosophical pessimism is an existential doctrine. It has real implications for the moral and existential conduct of life. If pessimistic convictions are ‘deeply cultivated’, as Buddhists say, they transform how we see and understand life. Worries about the disturbing nature of pessimism refer to this existential dimension. Taken seriously, life does not go on as before. Good doctrines of pessimism should guide the nascent pessimist in the conduct of their life. Processes of conversion to a pessimistic perspective can be steady or rapid, involving patterns of resistance and acquiescence. It often involves experiences of moral distress, even trauma. Becoming genuinely pessimistic can be transformative, in the sense made famous by L.A. Paul. If a doctrine involves transformation, trauma, and disruption, then its architects should build in guidance.

Pessimistic doctrines vary in their implications for how we should conduct our life. In his recent book defending pessimism, David E. Cooper distinguishes two broad kinds – nihilism and quietism (while rejecting activism and what he calls amnesia). The nihilistic options are the anti-natalist injunctions to voluntarily cease procreation to bring the human population down to zero and, related, the forms of ‘extinctionism’ that endorse human extinction as an aim or ideal. Nihilistic policies, being dramatic and extreme, unfortunately tend to dominate discussions of pessimism (Eduard von Hartmann’s call for the ‘universal suicide’ of humankind’ is alarming). ‘Anthropocene antihumanism’ is the name given to the idea that ‘a world without us’ would be better for the non-human animals and the natural world. Cooper rejects nihilism – these policies often involve very violent disruptive methods, sometimes fuelled by hate and other moral vices. It is also difficult to recruit people to these causes. Many are guilty of fantasy or pretence. Few of us have the power, social or technological, to actually help realise these scenarios.

Quietism refers to a gentler set of ways of trying to ‘live out’ an internalised pessimistic vision. Asceticism, retreats into ‘wholesome’ spiritual communities, the relief afforded by occasional ‘absorption’ in aesthetic experiences and the art of accommodating to the negative realities of life are all examples of quietist forms of life. Quietists are not passive in the sense of giving up on moral action—they do the little good they can without indulging delusions of amelioration on a grand scale. A sense of human limitedness can sustain a commitment to various virtues, as Cooper documents.

Pessimistic quietism is modelled by many people: ancients like the Buddha, Epicurus, and Zhuangzi, ‘recovering environmentalists’, like Paul Kingsnorth, and those countless and nameless people celebrated by George Eliot whose by their modest works add flecks of goodness to the world and now ‘rest in unvisited tombs’. Pessimists who recognise the deep badness of the human condition are not doomed to nihilism and despair. Other options – if modest and small-scale – are available.

Expanding our sense of the possibilities of philosophical pluralism is a crucial task in a world that seems determined to motivate pessimism.

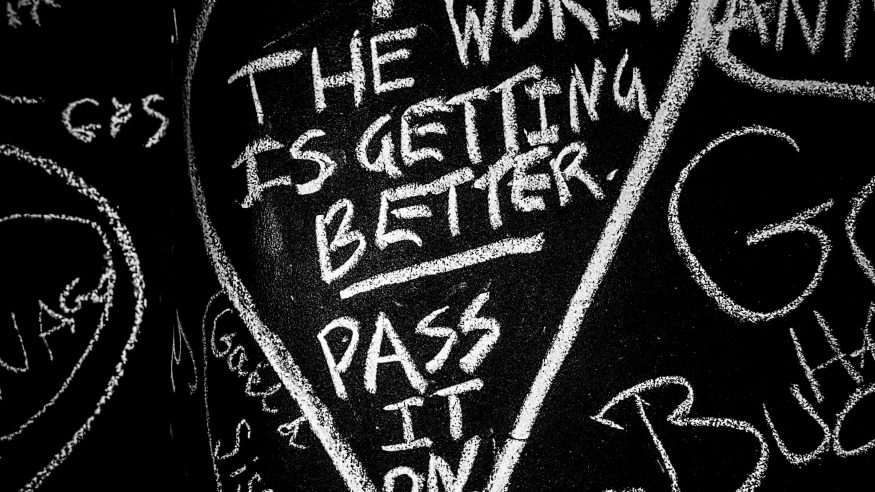

Photo by Mark de Jong on Unsplash

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017