AI voices should sound weird

19 August 2024

There has been a lot of discussion recently – both among academics and in the popular press – about what kinds of limits should be placed on content generated by AI. Although questions about how to implement them may be technically, legally, or politically tricky, there are very clear reasons for thinking some such limits are warranted. No one sensible wants to see more racist tirades like the one Microsoft’s chatbot Tay went on within hours of its introduction, and we will all be worse off if bad actors can rely on AI to learn how to do things like manufacture drugs or explosives.

My goal here will be to argue that in addition to limits on content, we should place restrictions on the forms that speech generated by AI can take. I will focus on the way such speech sounds – literally, what the voices it produces sound like – but similar considerations apply to signed and written language, too.

Some of the terrain here is very straightforward. Consider a recent case that attracted international media attention. The actor Scarlett Johansson claims that despite her refusing them permission twice, OpenAI used her voice to implement their ChatGPT virtual assistant. The company deny the allegation, although on the day the assistant was released, OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman tweeted the word “her”, which many observers have interpreted as a not-very -subtle reference to the 2013 film Her, starring Scarlett Johansson and telling the story of a man who falls in love with an AI whose most embodied feature is a bright and cheerful voice.

To use a person’s voice in this way, not only without their permission but indeed against their expressed wishes, is obviously unacceptable. But we might wonder – would things have been different if the actor had given her consent? What if the resemblance really had been a coincidence?

I think the answer to these questions is `no’. I don’t think AI voices should sound like any human voice, much less like that of a particular individual. At least until philosophers, linguists, and psychologists have had a chance to properly work through the sorts of issues I’ll discuss here, AI voices ought to remain stuck in the ‘uncanny valley’ – close enough to human to make their speech intelligible, but far enough that they produce feelings of alienness in listeners instead of empathy.

What might a voice from the uncanny valley sound like? The CUNY philosopher Daniel Harris recently pointed me towards the illustrative example of the character Data from the television show Star Trek: The Next Generation. Although the example isn’t perfect, the show’s writers have taken several steps to make the fact that Data is an android immediately audible. For one thing, except for the occasional slip from the human actor, Data avoids contractions. Instead of “I don’t” he says “I do not”, and instead of “goin’” he says “going”. For another – again, to the extent possible for an actor – Data’s speech lacks many of the subtle sonic cues that mark human speakers’ emotional inflections. To appreciate some of these, think of the way you might produce the greeting “How are you?” in a way that would convey warmth, excitement, or frustration.

The simplest reason to hobble AI voices with regard to their naturalness is that it would make the fact that they are AI voices readily apparent to human listeners. Transparency in this sense would serve several purposes. First, along the same lines as the warning labels that many have suggested should accompany images and content produced by AI, it would put people in a position from which they could make properly informed judgments about how much stock to put in what they hear. More like a watermark layered over an image than like a warning label or badge in the corner, the markers of artificiality would be present throughout an AI system’s speech, which might increase their efficacy. Second, this kind of consistent audible signal would address a worry about the role AI voices might otherwise play in undermining epistemic networks. If I don’t know which voices are human and which AI, and I don’t trust AI, I might respond by systematically lowering my trust in whatever I hear. Recent work on fragmentation and polarization suggests that this would be a bad outcome.

There’s a second reason for restricting AI voices to an unnatural range that is related to but distinct from the first. By making AI voices flat affect and clearly robotic, we might be able to reduce the risk of a powerful set of psychological and emotional tools being used to sidestep people’s rational engagement with the messages AI speech presents.

Many years’ worth of research in linguistics and in psychology has demonstrated that our impressions about the credibility of the people we talk to and the things they say, as well as our emotional responses to them, depend a lot on the way they sound. For example, people who speak with certain accents are judged to be more reliable sources of information than others, and there are patterns of pronunciation that systematically produce the impression that a speaker is friendly, the kind of person who has your best interests at heart.

It’s a totally normal feature of human life that we use these facts to navigate the social world. In a job interview, I might speak one way in order to create a certain impression, and at a party with dear friends, another. When I’m angry I sound one way, and when I’m asking for a favor, another still. Allowing artificial systems to reproduce the full range of human variation in these dimensions, however, may cause more harm than good. While there are clear reasons to do what we can to make a pilot more likely to listen when the computer says `collision warning!’, a world in which advertisers can speak to you in precisely the way their data suggests will be more likely to get you to make decisions that go against your interests seems like a bad one. So much the worse if the same goes for political messaging or legal advice.

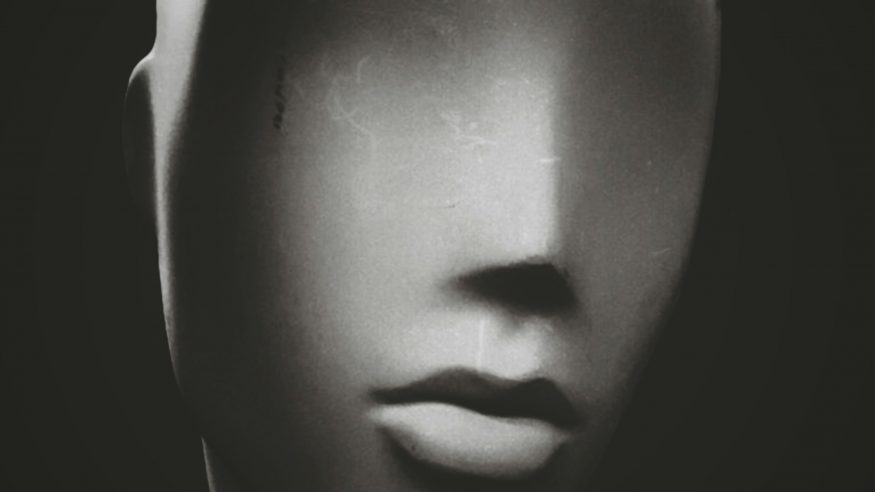

Photo: David Underland on Unsplash

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017