It’s English Language Day, but where exactly did the English language come from?

23 April 2020

By Ellen Bristow, School of English, Communication and Philosophy

Find Ellen on Twitter @E_Bristow1

Language, viewed from any perspective, is the human ‘miracle tool’. It liberated us from our earliest ape ancestors, gave rise to our history, and enables us to learn, innovate, develop and interpret the world we see around us. In particular, the English language is a major language of our globalised world. It is thought that approximately 379 million people speak English as their native language. Add to that the approximately 753 million who speak English as a second or additional language, and it’s easy to see the communicative significance of the English language in our world today. However, we rarely stop to think about where the modern English language we use everyday comes from. For example, if you were to ask your friend, ‘did you notice that surveillance photographer standing by that bungalow we walked past on our way back from Biology class?’, how many languages do you think you are speaking?

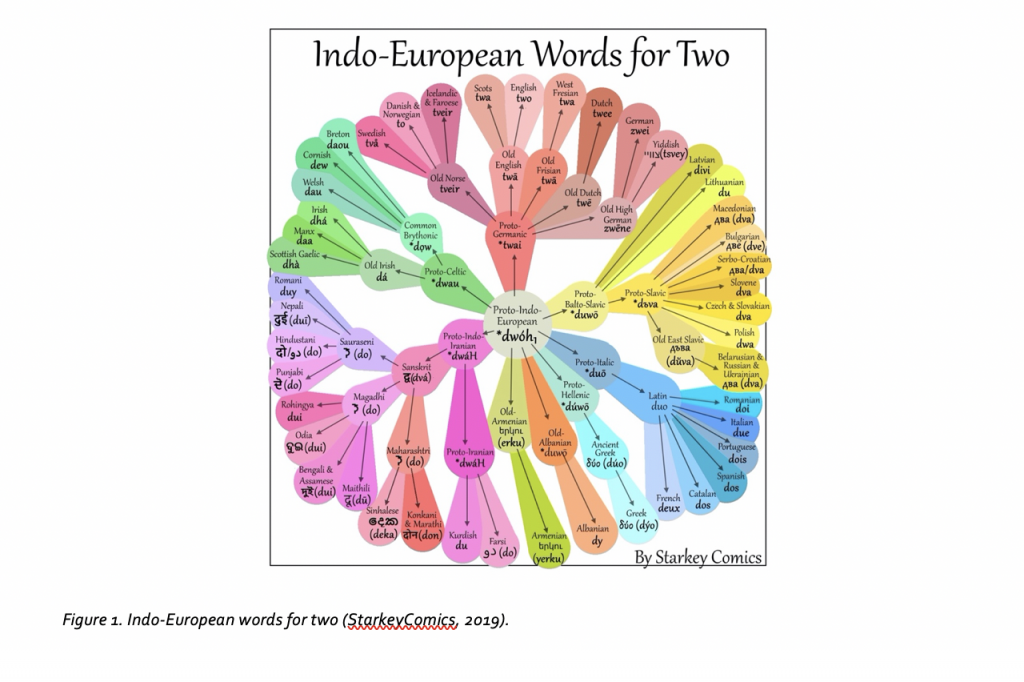

The obvious answer is, of course, one – English. However in this sentence alone, you would actually be speaking elements of nine different languages! The English language is, in fact, not really just ‘English’ at all, but an historic ‘mish- mash’ of numerous Indo-European and British colonial languages. Old English, Old Norse, Old Saxon, Old Frisian, Old French, Latin, Greek, French and Indian are those that influence the sentence above, but there are many more languages we have borrowed from, developed and adapted (see Figure 1). So, ‘why is this important?’, you may ask. Well, as a Linguist and English language educator, I argue that by understanding the history and composition of the English language, we are more able to understand, break down and interpret the complexities of our modern day vocabulary.

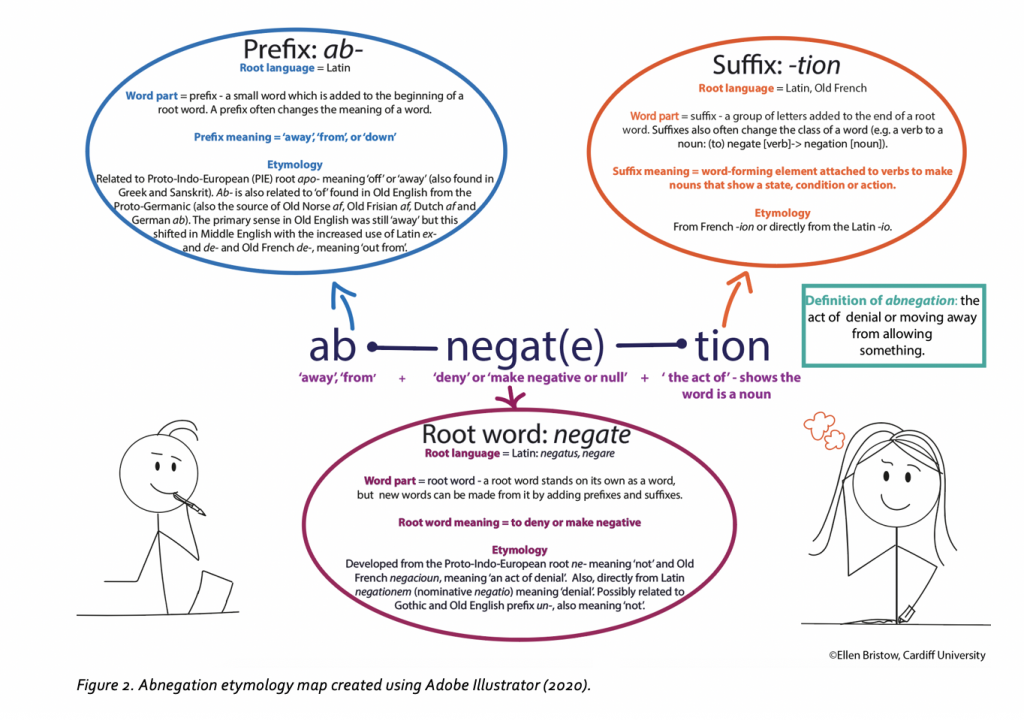

For example, consider the complex, multimorphemic (multiple part) word, abnegation, which appears on multiple lists as a ‘suggested you should know’ word for GCSE English language. Do you think knowing how to break abnegation down into its relevant word-parts (morphemes) and apply knowledge of the history (etymology) of the word, would help ours and school exam-sitters’ ability to understand the meaning of the overall word more easily?

I hypothesise yes; possessing these vocabulary deconstruction and decoding skills would help us to decipher the meaning of complex and unfamiliar vocabulary (see Figure 2). However, we still do not really teach English in this way in our schools. Occasionally, a ‘word-tree’ with roots and branches will be made or the meaning of a prefix or suffix explained but, currently, equipping children with the skills to deconstruct, decode and analyse the language used both in everyday life and in the academic school setting does not form part of the National Curriculum. It is important to question, therefore, whether it is a lack of these vocabulary decoding skills which further contributes to the ‘school vocabulary gap’. In this instance, the ‘vocabulary gap’ is a knowledge-difference between what the government and examiners expect children to know and understand compared to what GCSE pass-rate results suggest they actually know and understand. Moreover, evidence suggests this ‘vocabulary gap’ appears to be continually growing.

It is this concept that forms the primary objective of my PhD research and my overarching research question. My research asks: How does integrating word etymology and morphology into English Language teaching impact children’s academic vocabulary development? Working with numerous schools across Wales, I will test and trial different creative teaching strategies, such as ‘word-detective’ code cracking games, to explore whether explicitly learning these skills at a young age aids children’s vocabulary development. My hope is to understand which teaching methods will support child vocabulary development, so that by the time students sit that elusive English language GCSE exam, they have the strategies, tools and knowledge required to understand whatever vocabulary is thrown their way.

So, on English Language Day, I encourage you to think about what the term ‘English language’ really means. Use the fabulous Etymonline website to understand where just one word you’ve used today comes from. You’ll soon discover that whilst we think of English as just one language, it is a language comprising thousands of years of history and tens, if not hundreds, of international languages. Although we may all sound different when we speak, language connects us even more than we may think.

- February 2025

- September 2024

- June 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- Biosciences

- Careers

- Conferences

- Development

- Doctoral Academy Champions

- Doctoral Academy team

- Events

- Facilities

- Funding

- Humanities

- Internships

- Introduction

- Mental Health

- PGR Journeys

- Politics

- Public Engagement

- Research

- Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Staff

- STEM

- Success Stories

- Top tips

- Training

- Uncategorized

- Wellbeing

- Working from home