How can we personalise treatments for patients with breast cancer?

23 October 2019October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Here, Zoe Hudson from School of Medicine shares her research into the personalisation of breast cancer treatments.

Cancer is not just one disease and nor is breast cancer. Different cells in the breast can divide in an uncontrolled way and the tumours those cells produce develop lots of different ways of achieving their main goal; to grow, to spread and to be immortal.

The more we know about the subtle differences between tumours the better we can target treatments for patients so that they receive the best treatment for their tumour; either stopping it coming back or helping people with breast cancer live longer and feel better if their cancer isn’t curable.

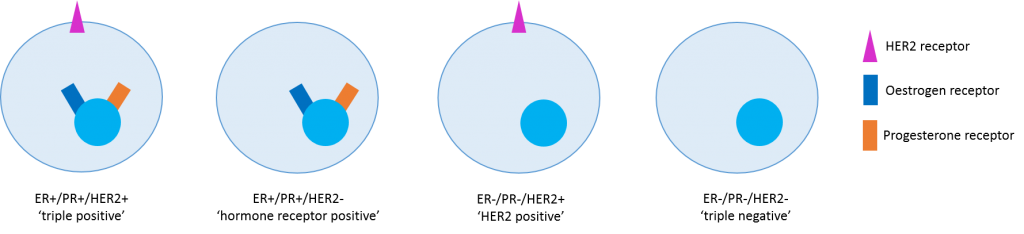

Doctors started personalising breast cancer treatment back in 1896 when Sir George Thomas Beatson published a report showing that removing the ovaries of people with metastatic breast cancer made their tumours shrink. What we now know is that many breast cancers have more hormone receptors (oestrogen and progesterone) than normal cells and this acts as an ‘on switch’ to encourage the cells to grow. We can now switch this off without surgery using drugs that stop hormone receptors working. Another growth receptor called HER2 can act in a similar way and we have good drugs that can switch this off too. We can test for all these proteins by staining tumour samples with special dyes. Tests for oestrogen receptor (ER), progresterone receptor (PR) and HER2 receptor (HER2) are routinely performed for all patients with breast cancer. If we imagine that breast cancers come in four different sub-types, then we can already begin to personalise therapy by targeting only the receptors that are present. However, what we are beginning to understand is that there are thousands of ways each subtype can differ.

My PhD focusses on the gene and protein variations that occur in one subtype – hormone receptor positive breast cancer. Over the last 10 years we have been able to read the genetic code of tissue and blood samples from people with many different types of breast cancer and this has taught us a lot about changes in genes which make the cancer more aggressive. Genes can be altered in lots of different ways but ultimately the changes lead to a protein that is unable to do the job it should.

Now that we know the sort of changes that are commonly found we can design better drugs to help patients. We are also able to find these genetic changes in blood samples from some people with breast cancer. This means they don’t need to have multiple biopsies. Changes in proteins such as PIK3CA and AKT1 can be targeted with drugs specifically designed to stop growth signals from these proteins going deeper into the cell.

A lot of breast cancers have genetic changes that mean that the normal safety checks which prevent damaged cells being able to reproduce don’t work properly. These changes are difficult to target with drugs because they are essential to all the cells in the body and blocking them would cause too many side effects. In these patients we might need new therapies, such as immunotherapy which uses the bodies own immune system to seek and destroy cancer cells.

My PhD has looked at a tiny bit of this big picture; using blood and tissue samples from patients to see if I can predict who will respond to a new treatment. The patients have all been part of a clinical trial which was designed and run by Velindre Cancer Centre and Cardiff University. The drug being studied puts a brake on a growth protein called RET which has been shown to be present in breast cancer cells where there are too many oestrogen receptors. The trial results should be available very soon and it will be exciting to see if we can find ways to predict who the treatment will help – another step towards truly personalised treatment for patients with breast cancer.

I am passionate about genomics and clinical trials. Now that we can read the genetic code of people with and without cancer so easily there are lots of ethical questions and things we need to think about as a society. My hope for the future of cancer treatments is that all patients will have the option of taking part in a clinical trial – this is the only way we will be able to make forward progress; answering for certain whether new drugs or treatments are better than what we are currently doing.

If you are interested in learning more about personalised medicine, genomics or clinical trials here are some highly recommended websites for further reading:

Get in touch with Zoe on Twitter @ZH_oncologist

- February 2025

- September 2024

- June 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- Biosciences

- Careers

- Conferences

- Development

- Doctoral Academy Champions

- Doctoral Academy team

- Events

- Facilities

- Funding

- Humanities

- Internships

- Introduction

- Mental Health

- PGR Journeys

- Politics

- Public Engagement

- Research

- Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Staff

- STEM

- Success Stories

- Top tips

- Training

- Uncategorized

- Wellbeing

- Working from home