The Empathy Defense: Emmett Till, “Open Casket,” and ‘White Empathy’

19 November 2018

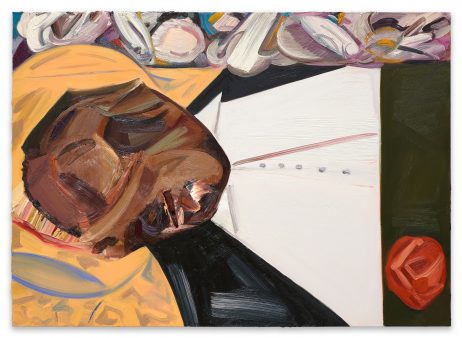

“A painting of a dead black boy by a white artist.” This is British artist Hannah Black‘s description of Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, a painting included in the 2017 Whitney Biennial and one that Black has urged be destroyed. The ‘dead black boy’ is Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955, and whose body, though brutalized and badly decomposed, was, at his mother’s request, laid in an open casket for the duration of a four-day public viewing. The description is a striking one. To some it will seem accusing and reductive, as though describing a painting with no artistic qualities, necessarily missing the point. To others, perhaps, it will seem frank and revealing, a description of a painting that reduces it to essentials, making the point.

In part, the issue turns on what Schutz’s relationship is to the gesture performed by Mamie Till Mobley, Emmett Till’s mother, and to the iconography associated with it, including the photographs of his body in casket that were published following his funeral and which played an important role in catalyzing the civil rights movement. Is Schutz, as some have claimed, attempting to reproduce Mobley’s gesture and, in that case, what would her failure to reproduce it mean? Would she, as implied by the protest staged before the painting, have made a spectacle of “black death,” an accusation deliberately resonant with associations to the tradition of lynching?

Schutz has said, in her defense, that her engagement with Till was “through empathy with his mother.” How, though, do we understand this defense in relation to the work? George Baker, an art historian, rejects the call for the painting’s destruction as authoritarian but, equally, rejects this defense, claiming that Open Casket reveals how naïve this conception of empathy must be: the work attempts, in particular, to collapse the distance between the artist’s “body” of work, abstract and suited to disfiguration, and Emmett Till’s own body, which was also rendered abstract through racial violence, also disfigured. The result, we are told, is an exercise in narcissism, bordering on the sinister.

This is, in my view, a profound misunderstanding of this defense and of the work. Schutz describes her empathy as being directed to Mobley, not Till, and she describes this connection as constituting a point of entry for the work, making it possible to engage Till, his death, its legacy, and its continuing relevance in a sustained and personal way. Regarding her connection to Mobley she says:

I don’t know what it is like to be black in America but I do know what it is like to be a mother. Emmett was Mamie Till’s only son. The thought of anything happening to your child is beyond comprehension. Their pain is your pain.

Schutz is not crediting herself in this passage (‘My being a mother gives me the right…’), but rather crediting Mobley; she is expressing her conviction, staked on her experience as a mother, that Mobley’s exhibition of the body of her son was performed as a mother, that his body, though brutalized, was also the loved body of her son. It affirms and expresses Schutz’s reliance on the possibility of looking at this body without seeing only the violence done to it. If violence is all that one sees, then perhaps there is only spectacle. Perhaps that would answer the question, “What does it mean to look without having to look away?”

There are, however, those who have wondered why, if Schutz empathizes with Mobley, she takes the body of Emmett Till as her (presumed) subject. This criticism presupposes too crude a conception of empathy and its role in the creative process unless it is seen, as I think it should be, against a deep suspicion of Schutz’s claim to empathy. “What is the interest in looking at this body?” it seems really to say. But this suspicion cannot run so deep without risking distorting the significance of Mobley’s act. Her motherhood was not disconnected from the presentation of the body or from the act of witnessing it. The suspicion directed toward Schutz cannot be so deep without being transferred to Till, as if his body is so ravaged by violence that it cannot hold meaning, as if it is not a mourned body but a motherless one.

We too often think of empathy as requiring us to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes and not often enough as requiring that we put ourselves in someone else’s hands. This can give the impression that empathy depends on the solitary exercise of imagination whereby we reproduce (or aim to) another’s understanding of things (it would be worth remembering here that ‘Put yourself in her shoes’ often has the force of a rebuke). This places emphasis on what this ‘power of imagination’ can accomplish, rather than on why empathy is needed. But empathy, where it holds out the hope of being transformative, is addressed to deep need; it takes place against the risk of isolation (where there is already distance). In some cases, the risk of isolation comes not from the fact that others do not understand one’s view of things, but from the fact that one needs others to support one’s coming to a view of things. That is, one can sometimes be lost even to oneself.

I propose that Schutz is not attempting to reproduce Mobley’s gesture, but attempting to respond to the call that is implicit in it. The attempt to respond to it is, precisely, aimed at addressing Mobley’s request that others (‘all of America’) see what she saw and, as she put it, that they tell what they had seen. As she recounts in Death of Innocence, she herself could describe what she had seen in forensic detail, part by part and inch by inch, but it was the impact of the body and its meaning that she couldn’t tell alone; others needed to be impacted too. Painting can facilitate bodily encounter. This is not to believe in the “magic power” of painting, as Baker says, ridiculing the claim that painting can facilitate empathy, but quite simply an aspect of the power of painting, both in its production and in our consumption of it. Schutz is, above all, I would suggest, a painter of the visceral body, of bodies under impossible demands, of bodies that are, therefore, not the bodies that we can or do see normally. This is the work of mourning in which Schutz is participating. And so, if we feel the urgency of locating Schutz’s position in relation to Mobley, we should begin with the possibility that Schutz joins her in the work of mourning and we should look to understand the painting in this light.

Empathy is a provocative defense, but Mobley’s action and call was also provocative. Those critics who have wished to understand or ‘place’ Schutz’s whiteness in connection with this work would do well to consider that Schutz’s reliance on Mobley is a form of mediation between herself and Till’s body and legacy (an indication that she does not and has reason not to simply trust her own looking). Still, there is, in this kind of empathy, an intimacy, a derangement of self and other. The mournful thought that Mobley experiences and that she invites others to as well also carries this risk; mournful thought can wander. It wandered, Mobley tells us, even in the courtroom in which Till’s murderers were being tried to their children who were playing on their father’s laps. It wandered from the thought of the grandchildren she would never have to the thought that she might be able to love those playing children (a thought that wakens her back to attention). Narcissism would be a failure of empathy, but not simply because it obscures the person with whom one empathizes. Its failure is also that it leaves one’s self in place, exactly where it was. Critics of the painting need to see it—though this may require hearing Mamie Till Mobley, perhaps for the first time.

Image: Dana Schutz, Open Casket, 2016, Oil on canvas, 38.5 x 53.25 inches. ©Dana Schutz. Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017