Mill and Ideal Theory

4 October 2021

John thinks that facemasks, social distancing and other public health measures are necessary to deal with the Covid 19 pandemic. He is aware that some disagree with him about this. But he hasn’t spent any time looking at their reasons for disagreeing. Should he spend time engaging with them and their arguments? Or should he just ignore them? More generally, should we engage with those who hold opinions that differ from our own?

Mill on Free Speech

One popular argument that we should engage with opposing viewpoints comes from John Stuart Mill. Famously, Mill thought that—with very few exceptions—you should be free to speak your mind, no matter what you want to say. But Mill didn’t just think that you should be free to say what you want. He also thought that others should engage with what you say. As he put it:

Truth has no chance but in proportion as every side of it, every opinion which embodies even a fraction of the truth, not only finds advocates, but is so advocated as to be listened to (On Liberty p. 49).

Mill reasoned as follows. Imagine someone wants to say something. If what they have to say is true, then obviously we should listen to them. But even if what they have to say is false, we still have a lot to gain from listening. There might be a grain of truth to what they have to say. Moreover, it is important to figure out why they are wrong. Engaging with opposing viewpoints ensures that we avoid dogmatism, keep an open mind, and stay intellectually curious.

Some think that Mill was wrong about this. While we sometimes gain a lot from engaging with opposing viewpoints, whether they are true or false, it is hard to see what recommends a general policy of doing so. Mill might have been right to worry that, if we don’t consider any challenges to our views, they will become “dead dogmas”—things we take to be true without knowing why. But why would we need to engage with anti-vaxxers to stop our view that vaccines are safe and effective becoming a dead dogma? More generally, what do we gain from engaging with people who seem to have no interest in reaching consensus, and often seem to view heated public debates as a way of pushing their political agenda?

Ideal Theory

If Mill was wrong, what could explain the evident appeal of his argument? We can explain its appeal as well as its limitations if we view Mill as engaging in what is called “ideal theory” in political philosophy.

Political philosophers are centrally concerned with justice. One way of understanding ideal theory is as a way of approaching the theory of justice. On the ideal theory approach, we ask what principles would govern a just society without worrying about whether people will comply with these principles, or about what justice demands of us in situations where they don’t comply. The result is a theory of what justice demands of us in ideal situations.

For its critics, the problem with ideal theory is that it is of no use in navigating actual, non-ideal situations. These critics hold that what justice demands of you in a non-ideal situation may differ from what it demands of you in an ideal situation. Take, for example, a pressing political question, like what we should do about the legacy of centuries of racial oppression. To answer this question, you can’t ignore the fact that the principles of justice are, and always have been, routinely flouted. In an ideal situation there would be no need to pay reparations because there would be no wrong to rectify. But in our actual, non-ideal, situation there is a wrong to rectify, and the question is what we should do about it.

Mill and Ideal Theory

Mill wasn’t offering a theory of justice, but he was interested in how we should interact with others. When we find out that someone has a different view to us, what should we do? Should we ignore them? Or should we engage? His answers to these questions make sense if we view him as doing ideal theory. If we assume that people generally comply with the principles governing social interactions (engage in good faith, back up your claims with evidence, be open minded) it is plausible that engaging with opposing viewpoints will have the benefits highlighted by Mill. If, on the other hand, we don’t assume this, it is far less clear that engaging with opposing viewpoints will have these benefits. Why would engaging with someone who engages in bad faith, doesn’t back up their claims with evidence, or is dogmatic, produce any tangible benefits?

Ultimately, whether you agree with Mill might depend on whether you think these assumptions are true or not. If you think that, on the whole, people engage in good faith, back up their claims with evidence, and so on, then you will likely think that, on the whole, engaging with opposing viewpoints brings tangible benefits. If on the other hand you think that, at least when it comes to certain issues, people often do not engage in good faith, then you will be skeptical. This explains the appeal of Mill’s argument, at least to those who think these assumptions are generally true. But it also explains the limitations. Those who think these assumptions are often false will reject it. Those who are unsure whether they are true or not will not be happy with an argument, like Mill’s, that just assumes they are.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Oliver Traldi for comments on an earlier version of this piece.

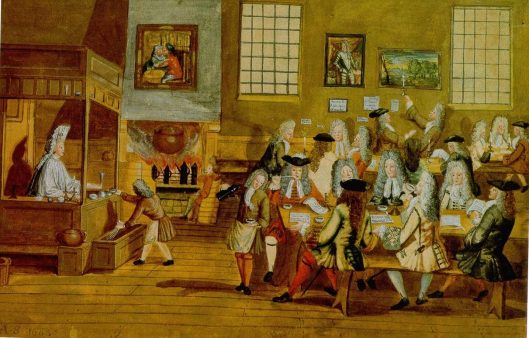

Picture from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c9/Interior_of_a_London_Coffee-house%2C_17th_century.JPG

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017