Speak Up!: Inquiry and Expressing Disagreement

16 July 2018

In 1994, Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray published The Bell Curve. In it, the authors notoriously argued that the difference in performance on IQ tests between members of different races is due to genetics rather than socialization. They argued that the difference between African American average IQ scores and white American scores is caused, at least in part, by genetic differences. They further argued that this difference in genetics also explains differences in income, job success, and criminality, among other things. These claims, according to Herrnstein and Murray, were the results of years of work in behavioral genetics.

The Bell Curve was met with wide public protest. There were sit-ins, and calls for Murray to resign his various academic posts (Herrnstein died soon after publication). Some behavioral geneticists, particularly those interested in animal behavioral genetics, dismissed the work as well.

However, the academic reaction was not entirely negative. In the 1995 keynote address to the Behavioral Genetics Association, Glayde Whitney, professor of behavioral genetics, suggested that Murray and Herrnstein’s work be pursued – that The Bell Curve opened many lines of important research. Then, an editorial in The Wall Street Journal, signed by fifty-two geneticists defended Herrnstein and Murray against accusations that their data and analysis were problematic.

Despite signing this editorial, many of these same geneticists thought that the science of the book was deeply flawed. Subsequent interviews with signatories to that editorial revealed that they never thought that the relationship between genetic correlates for intelligence and race were informative or even possibly informative. These scientists disagreed with the findings of The Bell Curve. They just didn’t say so (Panofsky, 2014).

It seems to me that these disagreeing scientists failed to behave properly on two counts. First, these scientists participated in the publication of an editorial that said, or perhaps implied, something they did not believe. They lied or misled the readers of that editorial and lying is often considered to be a moral failure. Second, these scientists ought to have said what they in fact believed. Intuitively, these scientists should have publicly expressed that they disagreed with the findings in The Bell Curve. And while both kinds of failures are interesting, it is this latter failing that interests me here.

This second failure – the failure of the scientists to say, publicly, that they disagreed with The Bell Curve might be a moral or practical failing – perhaps some moral harm was caused when people believed that these scientists endorsed The Bell Curve or the scientists had some practical duty to try to correct public opinion. However, this does not seem to fully capture the case. Even if nothing moral or practical were at stake, we’d think that the scientists should have said what they thought about the research. They should have done so because they were engaged in inquiry.

Inquiry involves using evidence and reason to make progress on some question or questions. It can be something as deep and important as the physical nature of the universe, or it can be something as ephemeral as where to go to dinner. And inquiry is what philosophers call an epistemic activity.

I want to suggest that, together with their moral and practical reasons to say that they disagreed, the scientists also had epistemic reasons to voice their disagreement with The Bell Curve. And if this is right, then when we’re in situations relevantly similar to that of the scientists, we have also have epistemic reasons to voice our disagreements.

Now, this does not mean that we have good reason to go around voicing all of our disagreements with every disagreeable statement we hear. I don’t (typically) have to tell a stranger I disagree with something she’s said. If, for example, I’m riding the bus and I hear someone claim that the fifth season of The Wire is the very best, I don’t have to chime in to disagree. Voicing all our disagreements would be rude, and exhausting, and it’s not clear how doing so would contribute to inquiry. Instead, we should voice our disagreements when doing so has the potential to improve or contribute to some inquiry we’re engaged in.

It also doesn’t mean that we should voice our disagreements to just anyone. Even if I’m engaged in inquiry about what to watch tonight, I don’t have a good reason to tell my fellow bus-rider I disagree with her television assessment. I have an epistemic reason to tell you about my disagreement insofar as I’m engaged in inquiry with you. So, if you and I are trying to decide what to watch tonight, I plausibly have an epistemic reason to tell you my views on The Wire – you and I are trying to investigate a question for which this disagreement is relevant and so I have epistemic reasons to express my disagreement to you.

Finally, it doesn’t mean that I have a reason to voice my disagreement in whatever way I please. If the scientists voiced their disagreements in cruel or excessively esoteric ways, their expressions would be unlikely to contribute to the inquiry they’re pursuing. Epistemic reasons are only one kind – I’ll also have moral reasons to be kind, practical reasons to be efficacious, etc. and meeting these requirements can help me in my pursuit of inquiry. One of our challenges, as inquirers, is to balance these (sometimes competing) reasons.

If I’m right then you ought, at least sometimes, to be telling people when you disagree. When you’re engaged in inquiry, when you won’t badly hurt someone’s feelings, when you can do so in a way that will help you pursue the question at hand, you ought to express your disagreements. Failing to do so is a kind of epistemic failing.

Panofsky, A. (2014). Misbehaving science: Controversy and the development of behavior genetics. University of Chicago Press.

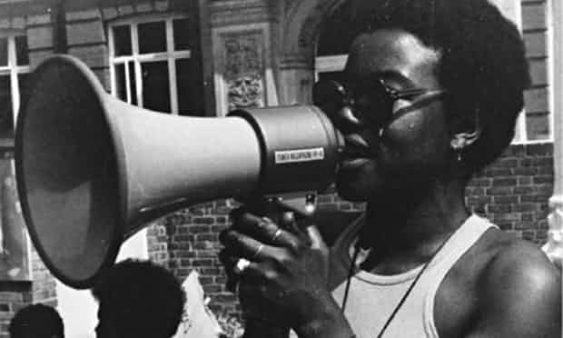

Photograph Olive Morris, Community Activist Photo: Lambeth Archives

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017