Egotism in Higher Education

9 August 2021

By Tracy Llanera and Nicholas Smith

Crisis or no crisis, vice-chancellors in Australia remain exorbitantly well-paid. While most of them committed to pay cuts in 2020 in response to the pandemic, the Times Higher Education points out that many university leaders are back to their seven-figure earnings this coming academic year. This is difficult news to swallow for the 17, 000 people in the Australian university sector who lost their jobs last year. Alas, the guillotine remains in place for more faculty and administrative staff in 2021.

In this debacle, Australian National University’s vice-chancellor and Nobel laureate Brian Schmidt stands out for negotiating his salary down to $484, 000 (AUD). On the one hand, this gesture seems morally praiseworthy: finally, a head who’s humbling himself by receiving only half of the average annual salary for a chief executive at an Australian university. On the other, why should this move strike us as heroic? The remuneration level for university leaders in the Global North is so outrageously high that even after a 50% cut it still looks generous. It can still feed the families of ten adjunct lecturers, who are among the worst off in this entire crisis.

But the ‘look after number one’ attitude of universities isn’t only on display in the privileges they accord to their bosses. Egotism has become endemic in all aspects of university life, transforming our very understanding of the purpose of higher education. We take egotism to be the attitude or cultural trait that (1) exhibits knowingness and self-satisfaction with one’s knowledge, status, and achievements; (2) encourages people and groups to think and act narrowly; (3) kills off the capacity to imagine and to inspire new possibilities and forms of life.

Many universities today have been cultivating an egotist culture and it has taken a global pandemic to fully expose its costs. These costs are not confined to the morally decadent gulf that exists between those at the top and the bottom. More subtly, they include a betrayal of the promise of a higher education; a dulling of the romance, the joy, and delight in learning that enervates our capacity for self-growth.

World Class Egotism

One of the first things anyone who works in or attends a university learns is the importance of appearing ‘world-class’. Look at the self-description of any university entity and it will be gushing with superlatives. In the clamour to appear the best, new ways of appearing even better and bigger than others must be invented. Amidst the subsequent madness, ‘excellence’ has become bog-standard and anything less than ‘well-above world standard’ is frowned upon.

Shameless boasting no longer raises an eyebrow. When parading to prospective students, all sorts of outlandish promises are made. Some universities claim that their curricula will ‘future-proof’ their students; that by doing their courses, they will be ‘job-ready’ whatever it is they go on to do. But how do these experts in curriculum design know what the future holds? And in any case, as Hannah Arendt once pointed out, isn’t the future for the next generation to make? In the current climate, even to ask such questions is to risk accusations of betrayal, of putting some nebulous ideal of education before the ‘real needs’ of students.

The practice of instrumentalizing higher education, of justifying university study exclusively in terms of the advantages it brings to a consumer in the job market, comes as at a price: it narrows higher education as a training ground for economic prosperity, for getting ahead of others, killing off any love that might be attached to university life. Universities appeal to and encourage the egotism of students by offering them a product whose primary use is to help them climb the professional and social ladder. But if students can only relate to their university education this way, they will miss what is arguably the distinctive and most important thing about it.

Delighting in Growth

Universities, ideally speaking, can be places that cultivate the process of self-growth. As the pragmatist philosopher Richard Rorty has put it, studying in universities allows students to undergo ‘self-enlargement’. Self-enlargement is Rorty’s take on what his fellow pragmatist and educationalist John Dewey called ‘growth’. Growth as self-enlargement occurs in two main ways: through projects of self-creation and widening relations of solidarity. Self-creation involves the making of oneself anew and the adoption for oneself of a ‘final vocabulary’, or a language that expresses one’s commitments, self-projects, and understanding and relationship with others and the world. Widening solidarity involves expanding the group to which one feels some belonging. At the heart of both are encounters with real or imaginary people, and these encounters reveal the limits and narrowness of one’s previous sense of self. In taking knowingness and self-satisfaction as its enemies, a culture of self-enlargement is the opposite of a culture of egotism.

When serving the goal of self-enlargement, a university education will be one in which the love of learning—doing experiments, reading books, engaging in conversation, learning from the experiences of people unlike ourselves, discovering the life of other communities, and so on—finds full and inclusive expression. Going to university, understood as a place where projects of self-creation and unknown solidarities beckon, would be more like entering a romance that inspires and expands one’s experience of life, rather than steeling oneself for success in a particular occupation.

Education for Democracy

It is also by realizing the goal of self-enlargement – by facilitating projects of self-creation and widening solidarities – that a university education contributes fundamentally to democracy. For democracy, understood not so much as a technique of government but as a way of living together, is precisely the form of collective life bound together by this ideal. The citizens of a democracy, in this expansive sense, are patriotic about the form of life in which individuals can recreate themselves within an ever-widening sense of community. As understood by Dewey and Rorty, democracy is fundamentally a growth-bringing, self-enlarging experiment in living – an education writ large in which everyone participates.

If this is right, then the problem with cultures of egotism is not just their epistemic arrogance and skill for romance-stopping: they are also a threat to democracy in the expansive sense. Egotism in universities is incompatible with their educative function in a democracy. Much of the misery of the contemporary university, its ‘dark side’, can be understood as a consequence of this self-absorbed culture. We should stand up to egotism, wherever it exists.

Note: This essay is based on the chapter “A Culture of Egotism: Rorty and Higher Education”, The Promise of the University: Reclaiming Humanity, Humility, and Hope, ed. Áine Mahon, forthcoming with Springer.

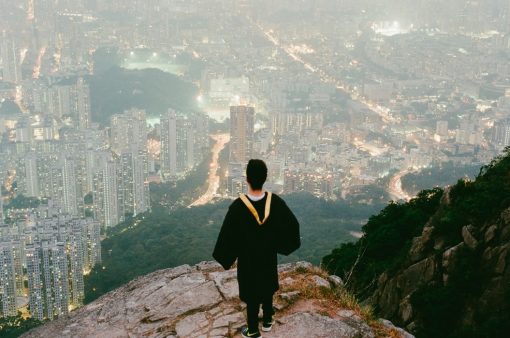

Stock Photo by Joseph Chan @yulokhan

https://unsplash.com/photos/YFhGIQhZsTU

Free to use under the Unsplash License

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017