Bad Questions Lead to Bad Democracy

9 October 2017

In a previous post, I discussed the essential role that questions play in the political landscape of contemporary democracy. The ability to ask questions, and to ask good ones at that, facilitates participation in political discussion and debate, allows us to gather information that speaks to our concerns, and those of our communities, and enables informed decision-making, about, for example, which box to tick on one’s ballot paper. Here I want to make the case stronger by looking at some of the ways in which bad questioning disrupts democratic processes and corrupts the institutions that we look to and reply upon in order to uphold the principles underlying them. I’ll focus on three common and familiar ways in which bad questioning causes and contributes to unhealthy democracy. These bad questioning strategies can be seen to obstruct and subvert exactly those benefits that arise from good questioning.

Firstly, take aggressive questioning. Aggressive styles of discussion and debate are commonplace in contemporary politics, where politicians, journalists, and other public figures are regularly seen to ignore or dismiss one another, raise voices, jeer and ridicule each other, and adopt dominating and hostile body language. This aggressive style is also manifest in a variety of questioning strategies, employed in order to obstruct participation in political discussion and debate:

Corbyn: “Can I, can I finish a sent…”

Paxman: “No!”

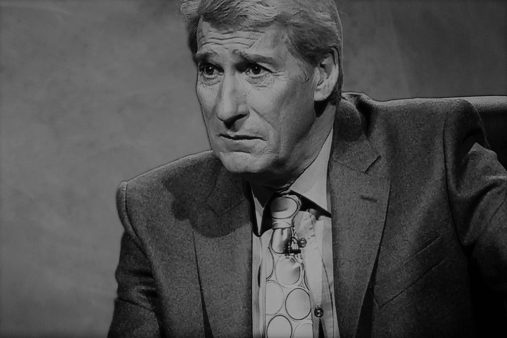

The quote above is taken from a televised interview with the leader of the Labour party, Jeremy Corbyn, prior to the UK’s national election in June 2017. A similar interview was conducted with the leader of the Conservative party, Theresa May. The interviews were hosted by Jeremy Paxman, a familiar face in British political journalism for over 30 years.

Paxman is well-known for his aggressive questioning style, which comes across clearly in the pre-election interviews where he employs several aggressive interview tactics, including many in the form of questions. This aggressive questioning is illustrated in the quotation. Paxman continually refuses to allow Corbyn and May to provide complete answers, or even finish a sentence. Instead, he repeats the same questions over and over again, without waiting for a response, and subsequently refuses to acknowledge any legitimacy in the half-responses that are given. By adopting this aggressive questioning style, Paxman prevents both of his interviewees from participating effectively in the discussion; an upshot that does not go unnoticed by the viewers. Comments posted on Twitter during the interviews reveal the frustration felt by those watching:

“Paxman seems to have forgotten that an interview is much better if you have the occasional answer. #BattleForNumber10” (Twitter user, David Schneider)

“I’m sorry Paxman but hectoring people rather than letting them answer the question isn’t skilful it’s really irritating #BattleForNumber10” (Twitter user, Kiri Tunks)

It is, indeed, hard to see any merit in Paxman’s aggressive questioning strategy, in this context. Insofar as democracy requires informed, open, and reflective debate among political leaders and a free press, preventing politicians from expressing their views on critical issues during a major televised interview, by interrupting their attempts to do so with repeated questioning, is obviously counterproductive. That is not to say that there is no place for aggressive, or at least forthright questioning, in political interviews, or political discourse more generally. As it plays out in these interviews, however, it appears inappropriate and obstructive. This aggressive questioning strategy is, of course, not confined to televised interviews with Jeremy Paxman, but rather found in political discussion and debate the world over.

Secondly, take closed questioning. Closed questions are questions that require an answer from one of only two options, typically yes or no. Again, Paxman provides a good example of this questioning strategy in the pre-election interviews where he asks persistently closed questions, requiring Corbyn and May to answer either yes or no. On the topic of nuclear disarmament, for example, he repeatedly asks Corbyn whether the renewal of the UK’s nuclear armament programme is morally right, accusing Corbyn of refusing to answer the question when he attempts to provide an answer beyond the basic yes or no. Likewise, on the topic of the UK’s recent referendum decision to leave the European Union, Paxman repeatedly asks May, if she has changed her position following the referendum result, insisting that she answer yes or no. In May’s attempt to respond, she makes a direct reference to the ‘tactic’ Paxman is employing, to which he retorts, “I’m just trying to get an answer, that’s all, you can say yes or no”.

By adopting this closed questioning style, Paxman simply fails to elicit any useful or relevant information on the topics discussed. Moreover, he prevents both Corbyn and May from giving due consideration to the questions asked, or framing a reflective and thoughtful response. Limiting the possible answers to questions on topics of such resounding significance and complexity, to a mere yes or no, radically diminishes the potential for informative discussion and debate concerning these issues. As a result, the viewer’s opportunity to gather information on these topics in order to make informed decisions on this basis is, likewise, radically diminished.

Again, it is hard to see any merit in Paxman’s closed questioning approach, in this context. Insofar as democracy depends upon an informed populace, with respect to issues such as nuclear armament and national identity in the run-up to a national election, limiting politicians to yes or no answers is inappropriate and obstructive. That is not to say that there is no place for closed questioning, in political interviews, or political discourse more generally. In the pre-election interviews, however, we see a clear instance of the disruptive deployment of this questioning strategy. It is bad questioning. This illustrates the significance of not merely asking the right questions, but asking them at the right time and place, and in the right manner. Again, the import of this is not limited to televised interviews with Jeremy Paxman but is likely to resonate with anyone who has witnessed or been at the receiving end of closed questions, be it in a court of law, or over a pint in the pub!

Thirdly, take loaded questions. Paxman’s repeated questioning of Corbyn over whether the renewal of the UK’s nuclear armament programme is ‘morally right’ offers one example of such questioning. Here Paxman builds into his question an assumption that the issue is a moral, rather than, for example, prudential one. Perhaps he is right to do so. Nonetheless, the question is loaded. A good example of the use of loaded questions in a quite different context can be found by looking at the original questions posed for both the Scottish independence referendum, in September 2014, and the UK’s referendum on EU membership, in June 2016. In the former case, the original question read: ‘Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?’ Commentators, however, argued that the question was loaded in the sense that it framed the issue of Scottish independence in a particularly positive light and would lead the answerer more naturally towards a simple yes, rather than reflective consideration of both yes and no. In this case, given the significance of the issue at stake, the question was ultimately changed to read: ‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’ Similarly, the original question for the EU referendum read: ‘Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union?’ Again, commentators argued that the question would lead the answerer more naturally to a simple yes. Consequently, the question was changed to ‘Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?’.

Despite these successful changes in the referendum contexts, loaded questions are often employed in more informal political settings in order to lead or even manipulate people into arriving at one answer rather than another. Loaded questions obscure the salience of one issue whilst emphasizing the significance of another. As such, they play a particular role in impeding informed decision-making. Insofar as democracy requires citizens to make informed decisions, in the politics of everyday life, and the politics of nation-states, loaded questions emerge as an especially pernicious form of bad questioning. That is not to say that there is no place for loaded questions, but their use, with respect to issues of heightened political significance, in particular, should be carefully considered. The example of the referendum questions illustrates just how significant the questions can be.

I have discussed just three ways in which bad questioning can and does undermine key democratic principles. The same can be said of many other types of bad questions and bad questioning strategies including misdirected questions, misinformed questions, and questions asked of the wrong people, at the wrong time, in the wrong way. There are, moreover, many subtle variations and nuances to these kinds of bad questioning practices, that I have not discussed. It should nonetheless be clear that, just as good questioning is vital to good democracy, so bad questioning, if left unchecked, may lead to its demise.

I will be discussing the bad questioning practices described here, in more detail, in an upcoming presentation for the Changing Attitudes in Public Discourse conference, at Cardiff University, and will subsequently be developing these ideas for publication. You can find drafts and final versions of all my papers at philosophyofquestions.com/publications.

Image: ‘The Paxman Stare’ by Dullhunk on Flickr

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017