Can UK fossil fuel companies now be held accountable for contributing to climate change overseas?

2 July 2020

Sam Varvastian, School of Law and Politics

A ruling by the UK Supreme Court could have huge implications for British companies accused of environmental damage overseas. The April 2019 decision, in a case brought by a group of Zambian farmers against a London-based mining firm, establishes that UK parent companies can be held liable under UK law for the actions of their foreign subsidiaries. I analysed the implications of this case together with my colleague Felicity Kalunga, a PhD researcher at Cardiff University and a legal practitioner in Zambia, and our findings have just been published in Transnational Environmental Law.

The idea of corporate accountability for climate change is not new. More than a decade ago, a group of US citizens whose property was destroyed during Hurricane Katrina sued some of the world’s largest fossil fuel companies, including ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP and others, claiming that the greenhouse gases emitted by these companies contributed to climate change, which added to the ferocity of the hurricane, thus causing greater harm. Around the same time, an Alaskan village sued the very same companies, seeking compensation for its forced relocation resulting from melting sea ice.

Both cases were dismissed, and the courts did not even address the question of whether companies can be held accountable for climate change. But similar actions have since emerged around the world, with the US being a hotspot for such lawsuits.

For their part, the UK courts have not yet addressed the issue of corporate accountability for climate change – perhaps surprising, since some British companies, most notably BP, are among the largest corporate contributors to global greenhouse gases. This, however, may change soon, and it may not be just UK claimants suing UK companies, but also foreign claimants, pursuing litigation against these companies for their foreign subsidiaries’ contribution to climate change.

Zambian farmers go to court, in the UK

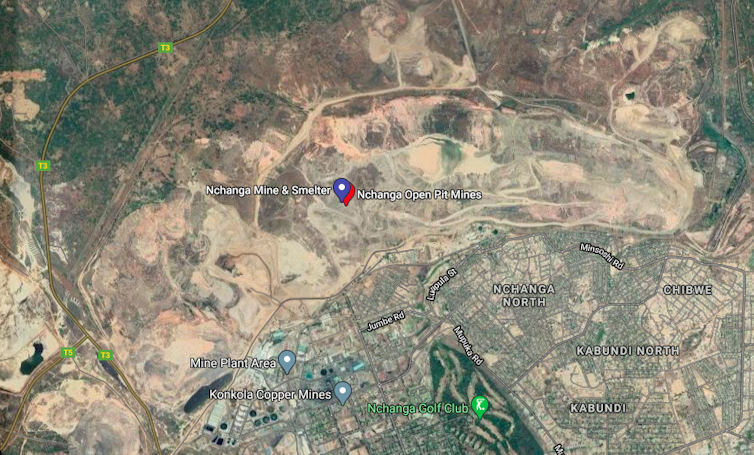

A catalyst for this could be the decision of the UK Supreme Court in the case mentioned above: Vedanta v. Lungowe. At first glance, the case has nothing to do with fossil fuels or climate change. The case was brought by a group of 1,826 Zambian farmers, including one Mr Lungowe, who claimed that a copper mine had been discharging toxic emissions into the local watercourses used for drinking and irrigation.

The mine was operated by a local subsidiary of Vedanta, a huge global mining company headquartered in the UK. And it was the parent company that the claimants sued, and the jurisdiction of the UK courts that they sought. The farmers were represented by a London law firm Leigh Day on a “no win, no fee” basis.

The claimants’ theory was that the UK company had control over the operations of its Zambian subsidiary, as proven by the materials published by the company itself. Pursuing litigation against the subsidiary in Zambia would be ineffective for various reasons, including the subsidiary’s uncertain financial position and the lack of lawyers there experienced in dealing with such a case.

After nearly four years of litigation, the UK Supreme Court confirmed: UK parent companies can be held liable in such cases and UK courts have jurisdiction to hear such claims. This allowed the farmers to proceed with their substantive claims heard in the UK.

Parent companies are being held accountable

The decision is consistent with a growing trend of holding parent companies accountable for environmental and other harms caused by their foreign subsidiaries. France is one of the most notable examples. The country recently adopted a special law requiring large French companies to “establish and implement an effective vigilance plan” so as to prevent environmental damage caused by their and their subsidiaries activities, both in France and abroad.

The principle behind the UK decision may allow courts to consider cumulative greenhouse gas emissions from both a parent company and its subsidiaries. Taken separately, emissions from a single subsidiary may easily be considered too insignificant to make any meaningful contribution to climate change and any resulting harms. Yet, suing these subsidiaries alongside their parent companies (especially such fossil fuel giants as BP, whose emissions are considerable on a global scale) could be a more viable option for foreign claimants.

A co-benefit of this is that by demonstrating the presence of UK parent companies abroad through their subsidiaries, foreign claimants may have better chances of persuading UK courts to hear such claims instead of dismissing them for the lack of jurisdiction. This in turn could lead to more effective enforcement of courts’ decisions.

Finally, a somewhat more speculative, yet potentially possible reason for suing parent companies could be related to the recent announcements by some fossil fuel companies, including BP, that they will become net-zero. In practice, this could simply mean outsourcing emissions through their multiple foreign subsidiaries. Such a scenario would be quite consistent with claims that BP engages in “greenwashing” (a claim the firm “strongly rejects”) and new evidence that it knew about the climate impact of fossil fuels long before it publicly acknowledged the reality of climate change.

It is too early to predict whether such “climate” lawsuits could succeed in the UK, but it may well be that UK courts will soon have to answer this question.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- February 2025

- September 2024

- June 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- November 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- Biosciences

- Careers

- Conferences

- Development

- Doctoral Academy Champions

- Doctoral Academy team

- Events

- Facilities

- Funding

- Humanities

- Internships

- Introduction

- Mental Health

- PGR Journeys

- Politics

- Public Engagement

- Research

- Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Staff

- STEM

- Success Stories

- Top tips

- Training

- Uncategorized

- Wellbeing

- Working from home