The price is (not) right: surveying the Welsh house price boom

1 July 2021Today marks the end of the Land Transaction Tax (LTT) holiday in Wales. Property purchases over £180,000 will no longer qualify for the temporary tax relief worth up to £2,450.

While the impact of the policy is yet to be fully evaluated, it is undeniable that the property market bears little resemblance to how it looked a year ago.

Bounce back

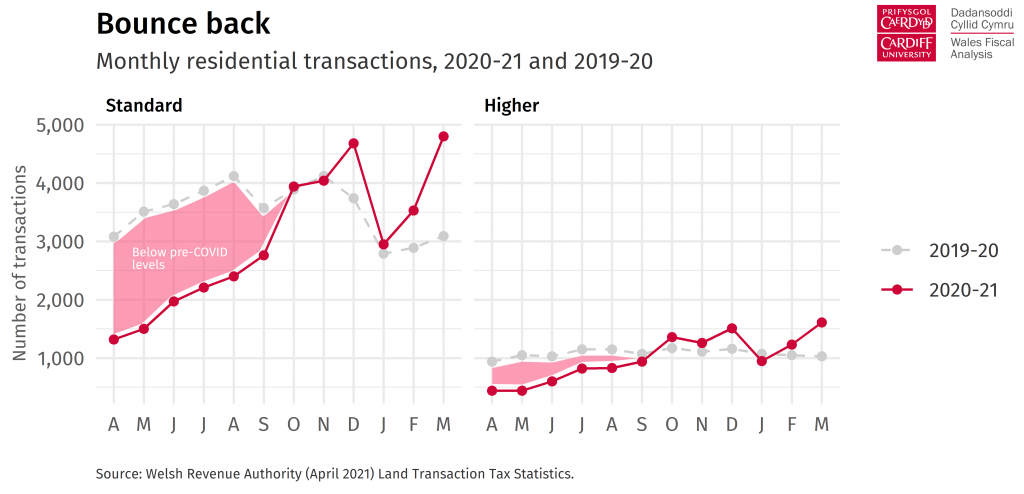

When the first lockdown measures were announced in March 2020, property viewings were suspended, and the number of transactions slumped.

But by the Summer of 2020, there were signs that the tide had begun to turn.

Buoyed by a temporary reduction in tax rates, the volume of transactions swiftly increased. Many of those who had deferred their house move during the first lockdown could now go ahead with their purchase. The widespread adoption of homeworking meant that a newly mobile class could entertain living outside the commuter belt for the first time, contributing to faster house price growth in rural areas.

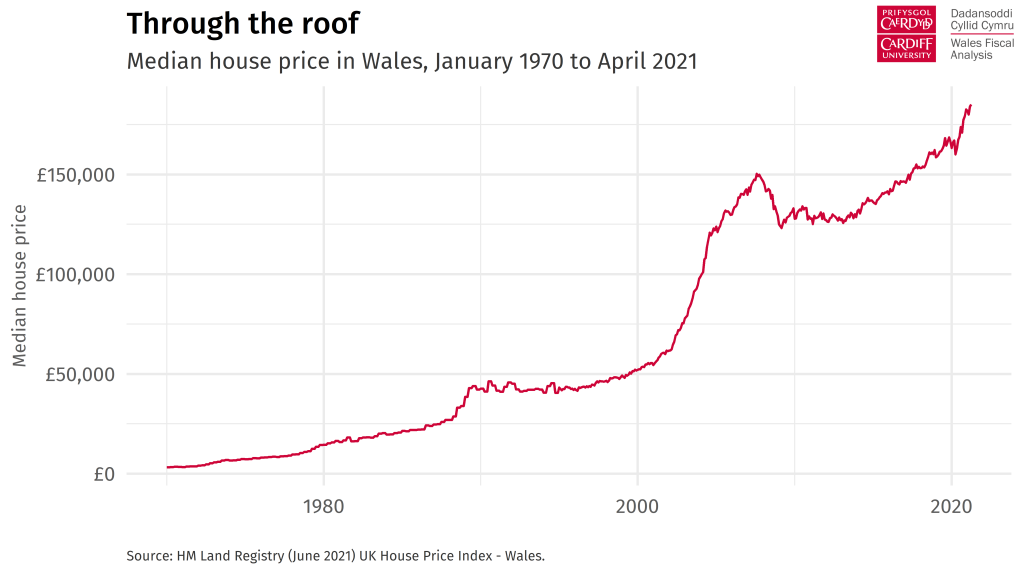

According to HM Land Registry, house prices in Wales increased by 15.6% over the year to April 2021 – higher than any other UK country. Although some of this increase can be chalked down to a base effect (the figure is reduced to 10.2% when measured over the 12 months to March 2021), it still marks a recent historic high.

In December, the Welsh Government increased the higher tax rates applied to transactions made by owners of multiple properties (these transactions were already exempt from the LTT holiday). But despite this intervention, the proportion of transactions charged the higher rates has remained broadly constant over the course of the year.

Following a brief slowdown over the Winter months, the number of transactions once again surged ahead of their pre-Covid levels in the first quarter of 2021. In response to this strong outturn data, the forecast for residential LTT receipts was revised upwards by the OBR earlier this month.

Priced out

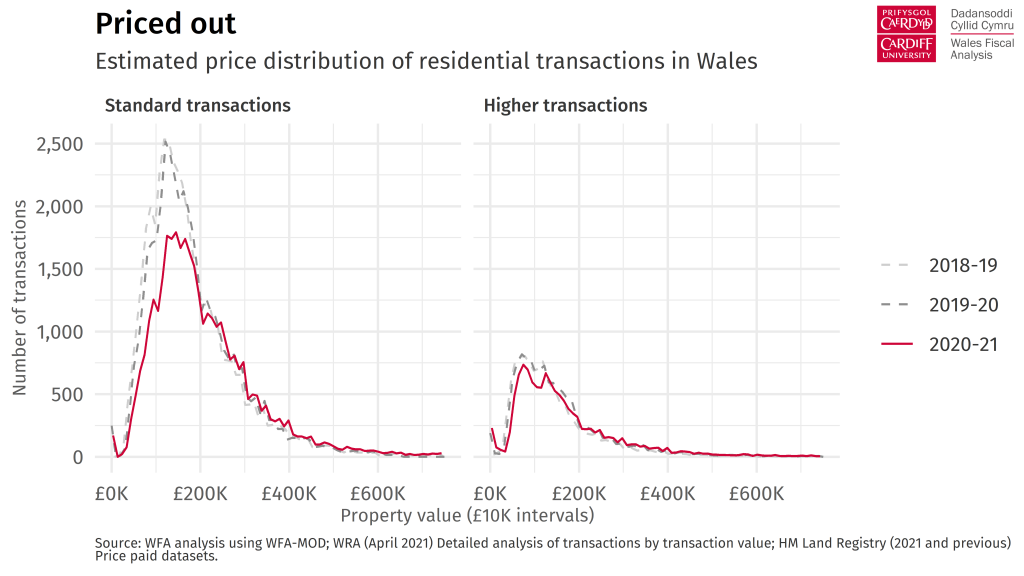

Our in-house LTT model allows us to take a more fine-grained look at changes across the price distribution.

Unsurprisingly, the reduction in the volume of transactions in 2020−21 has been particularly pronounced in the lower price bins.

Although there has been little change in the volume of transactions subject to the higher rates, the reduction in the number of standard rate transactions at the lower end of the price distribution means that the proportion of lower priced properties purchased by owners of multiple properties has increased.

In 2020−21, approximately 1 in 3 residential properties purchased for less than £180,000 were subject to the higher rates of tax.

On the face of it, a decrease in the number of properties purchased at the lower end of the price distribution is a logical consequence of growth in house prices. But the picture is somewhat more complicated.

If house prices had increased uniformly, we would intuitively expect the price distribution to shift (graphically) to the right, whilst retaining its shape. But this does not appear to have been the case. The bunching of transactions below the tax-free threshold seen in previous years has given way to a more even spread of transactions below £200,000, while the top half of the distribution remains virtually unchanged.

There might be a couple of explanations for this.

First, it could indicate that the growth in house prices has been, in part, compositional – for whatever reason, owners of higher valued properties might have been more inclined to put their property up for sale over the past year, resulting in a higher-priced, tax-rich pool of transactions.

Second, this could potentially be a distortionary effect linked to the Land Transaction Tax holiday. Although further analysis would be required to establish a causal relationship, previous research has shown that when a Stamp Duty holiday was introduced in the UK following the last financial crisis, the majority of the value of relief fed through to higher prices. Intuitively, this effect would likely be stronger around the original and revised tax-free thresholds.

Through the roof

Regardless of what has been the driver of the recent house price boom, housing has become even more unaffordable for many.

According to research by the Resolution Foundation, the average Gen-X first time buyer born in 1972 had to save until the age of 22 to get onto the housing ladder, but the average millennial born in 1984 will need to save at the same rate until the age of 34 to purchase their first property.

Increasingly, inherited wealth plays a much bigger role in determining the lifetime economic resources of younger generations.

Even worse, we know that this wealth is unevenly distributed. Across the UK, the top half of households aged over 80 hold 90% of the wealth, and the top 10% alone hold 40% of the wealth.

And without access to affordable homes, a growing share of the population are effectively locked out of all the other considerable benefits linked to housing tenure.

Private renters in the UK are over seven times more likely to be overburdened by housing costs (where total housing costs exceeds 40% of disposable income) compared to owner-occupiers. Last year, we set out how private and social renters were more vulnerable to a loss of income because of Covid-19. More recently, the Bevan Foundation revealed new data showing that 6% of Welsh households have already been told that they will lose their home, with a further 8% of renters (and 4% of owner occupiers) worried that they might lose their home in the next three months.

Although the Welsh Government recently announced a new grant scheme to assist tenants who have fallen behind with their rent payments, protection against eviction was recently lifted. By contrast, commercial tenants in England have been granted a moratorium on evictions until March 2022.

Of course, few would disagree that there is an urgent need to ensure the availability of affordable housing, but fewer might be willing to acknowledge that the historic gulf between growth in earnings and house prices is neither a desirable societal outcome nor a laudable policy aim.

Though there is unlikely to be a silver bullet, there are a few policy levers available to the Welsh Government.

The higher rates of LTT could be adjusted to further discourage property speculation. Premiums applied to second homes that are empty most of the year could be used to disincentivise inefficient use of existing housing stock. More local discretion could allow these policies to be better tailored to the needs of communities, as recommended in a report authored by Dr Simon Brooks.

Supply side issues should not be overlooked either. Changes to planning law and increased construction of social housing could alleviate some of Wales’ housing need.

With people spending more time than ever at home, the pandemic has underlined the importance of safe, affordable and secure housing. Ensuring an adequate supply of affordable homes, secured long term, should be a priority.

Read more by WFA…

- June 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Rugby

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections