When ends don’t meet: tax rises and benefit cuts (Part 1)

15 October 2021

In the first of a three-part blog series on Welsh household finances, the Wales Fiscal Analysis team examine the impact of the recent cut to Universal Credit and planned tax rises on households.

The Spending Review may not be due for another two weeks, but the Chancellor has already committed to major tax and benefit changes over the coming months.

Following last month’s announcement of a new Health and Social Care Levy, taxes are set to rise to their highest sustained level in UK peace-time history. Meanwhile, the decision to withdraw the £20 a week uplift to Universal Credit leaves unemployment support at its least generous since the Second World War.

For many households in Wales, the impact of these policy changes will be considerable.

Cut by the thousand

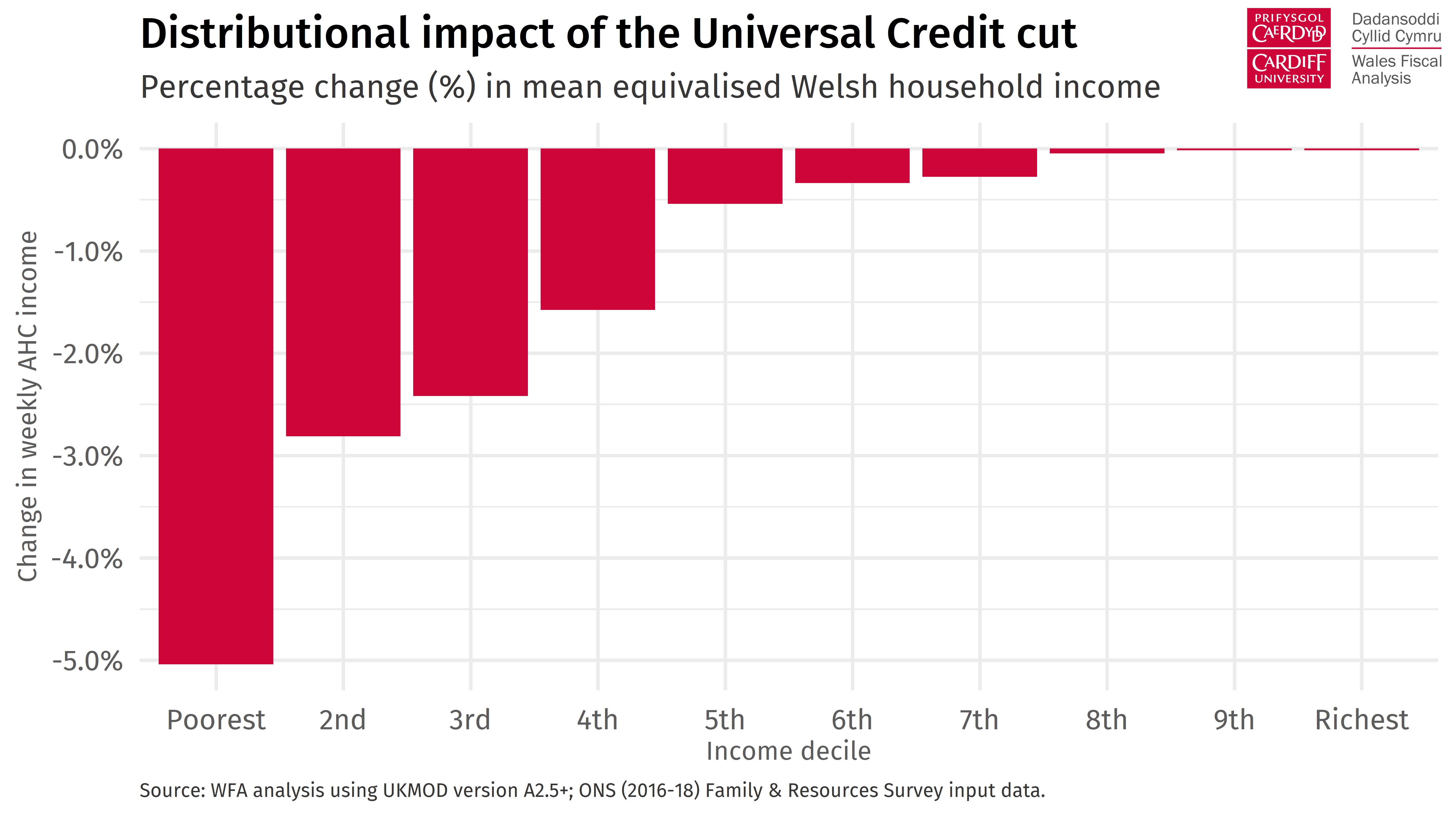

We estimate that 20% of Welsh households will have been impacted by the cut to Universal Credit last week. Households in the poorest decile saw their income fall by more than 5% overnight.

For some population groups, the impact was greater still. Approximately a third of households with children saw their incomes reduced, as did half of single parent households, with almost a third of those losing at least 5% of their income.

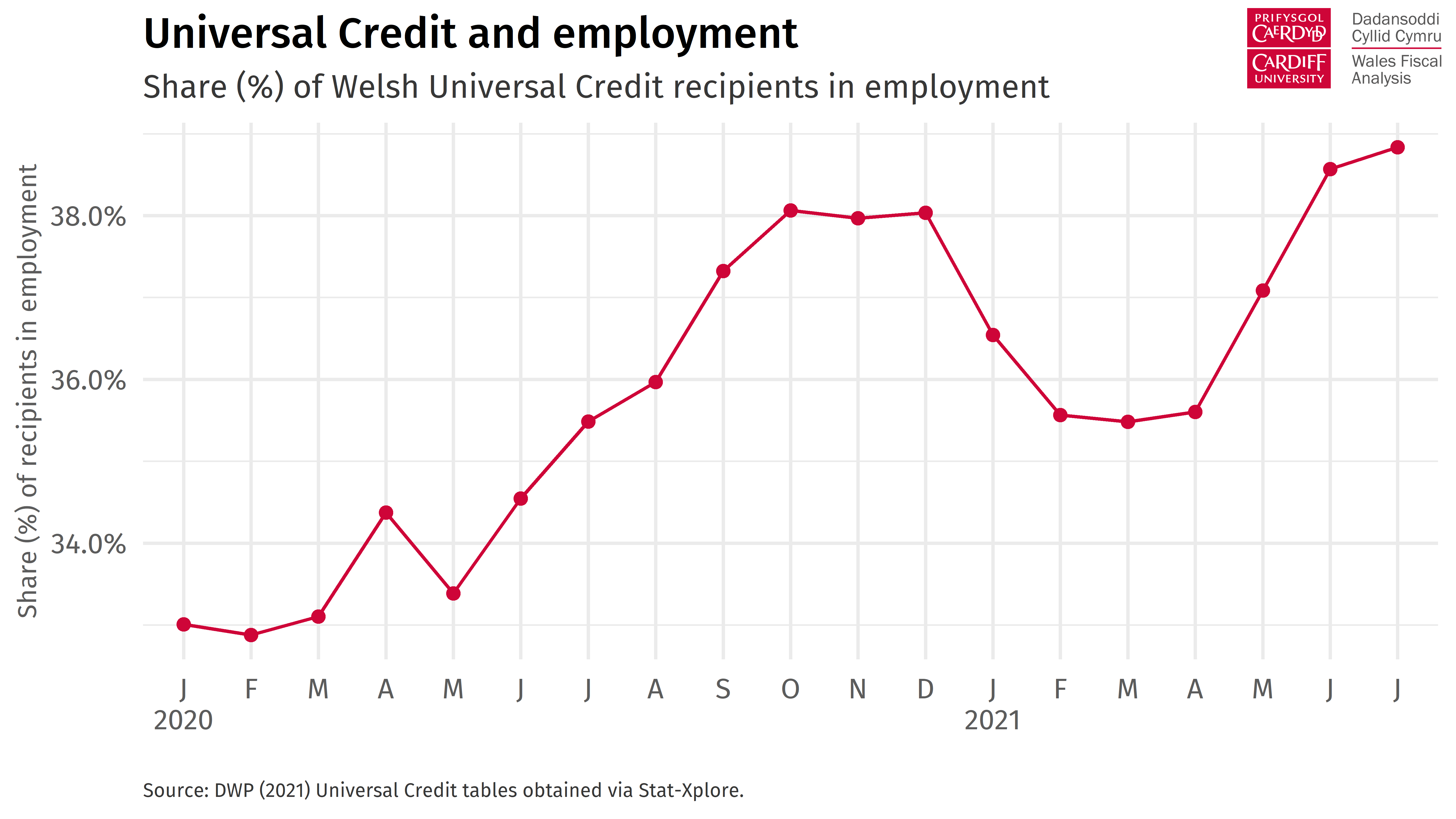

Despite the high vacancy rates and labour shortages in some sectors, it is unlikely that cutting Universal Credit will significantly shift labour supply.

Apart from the Winter lockdown period, the proportion of Welsh Universal Credit recipients in employment has steadily increased throughout the pandemic.

Moreover, it is well-established that many Universal Credit recipients face considerable barriers to working more hours due to the combination of a high marginal withdrawal rate (the rate at which the Universal Credit award is reduced for any given increase in earnings), and high costs associated with commuting and arranging childcare.

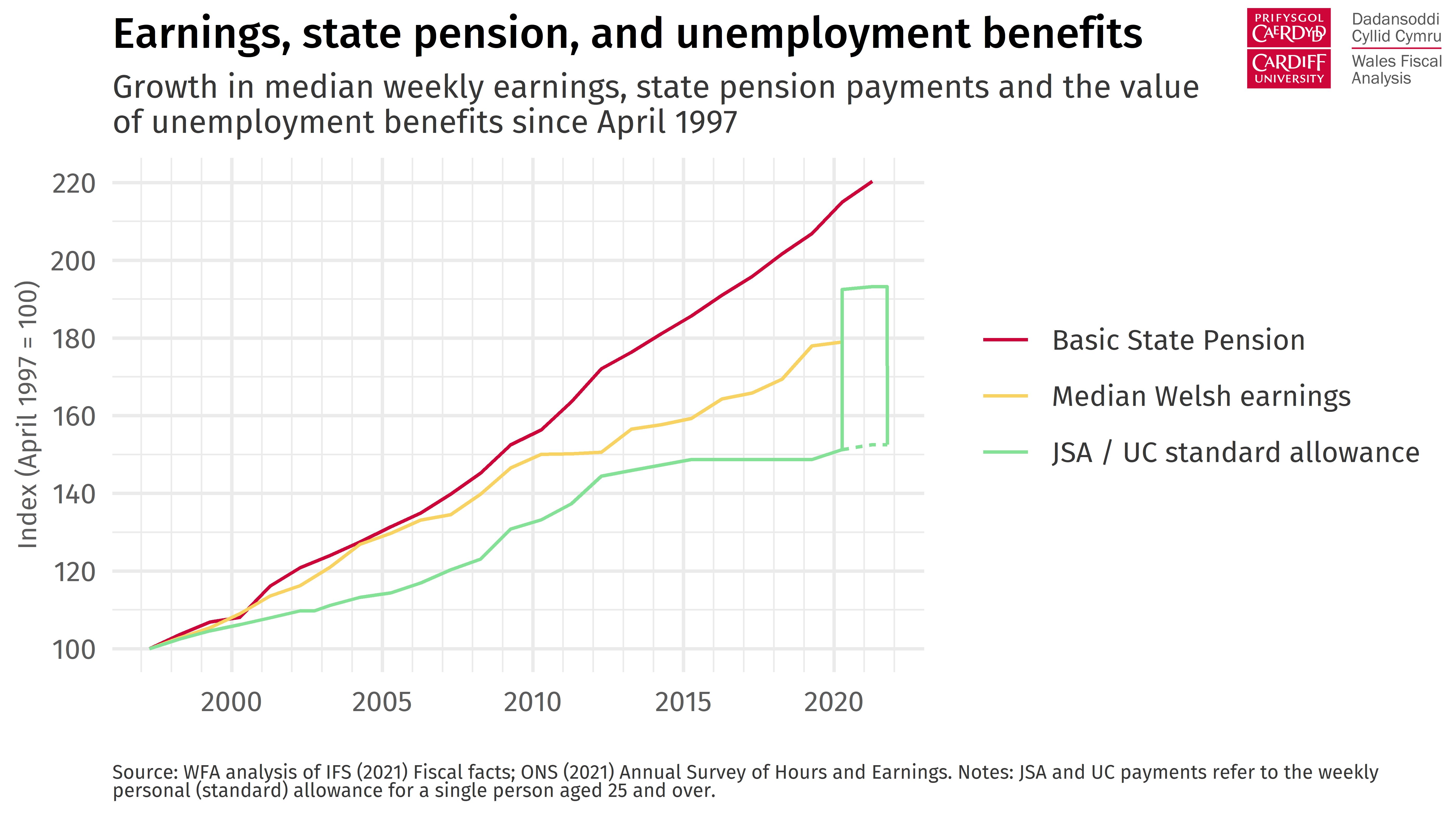

Although the £20 a week uplift represented the largest ever overnight increase to the standard unemployment benefit; even when boosted, it was not out of line with past levels. Far from it.

Lagging behind

The value of unemployment benefit in the UK was historically linked to the basic state pension, with both rising in tandem for several decades. They became decoupled in the late-1970, after which, their trajectory diverged significantly.

Since 1997, the standard unemployment allowance has grown at only half the pace of the Basic State Pension, and only two-thirds that of median Welsh earnings. It has also trailed consumer price (CPIH) inflation, largely due to the “benefit freeze” implemented by the UK government in the second half of the 2010s.

Now that the uplift has been withdrawn, unemployment support stands at 14% of median Welsh earnings, its least generous level since Welsh earnings records began in 1997. As a share of UK earnings, it is at its least generous level since the founding of the welfare state in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Taxing times

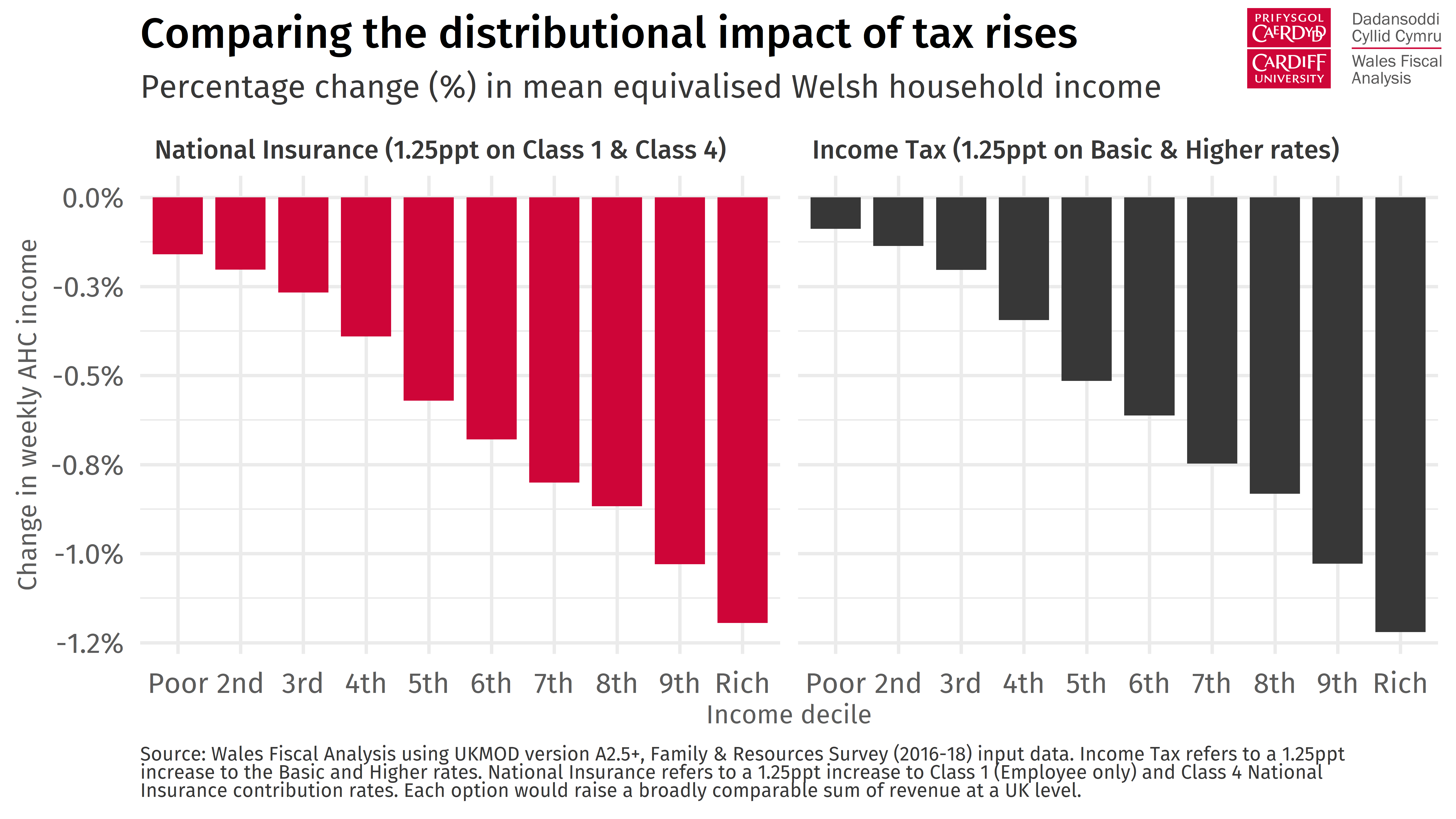

From April 2022, national insurance rates for employers, the self-employed, and employees will increase by 1.25ppt to fund increased spending on health and social care services.

Though not quite as progressive as an income tax rise might have been, the policy is still progressive with respect to earnings. Higher-earning households will forego a larger proportion of their income when paying this new levy.

However, there are other reasons why an income tax rise may have been preferable.

National insurance, unlike income tax, is not paid on unearned income from investments, rental properties, and pensions. Although the Treasury waived the usual national insurance exemption for employed individuals who have reached the state pension age, those who have already retired will not contribute anything.

Not only this, but the way national insurance is calculated – on a weekly rather than an annual basis – means that the new levy could disproportionately penalise those who are paid irregularly, perform seasonal work, or become unemployed during the year.

And there are also questions about the wider implications of the UK government’s plans for social care reform.

On the one hand, the UK government’s decision to put an upper limit on how much people in England will have to pay for their care is a welcome one. It goes some way towards resolving the contradiction whereby older people requiring health care for acute conditions received treatment for free by the NHS, while those requiring personal care for degenerative or chronic illnesses are often required to meet the cost themselves.

But in the absence of other policy interventions, the proposed arrangement is tantamount to a transfer from working-age individuals to asset-rich pensioners.

Given the evidence of a growing inter-generational wealth gap, and the increasing number of younger people who are priced out of the property market, the reforms are likely to further legitimise concerns about generational unfairness.

Tax – and benefit?

From a budgetary perspective, Wales stands to benefit from the decision to raise taxes at a UK-level (and to subsequently receive its population share in consequentials) rather than using the devolved tax levers.

Moreover, since care home residents in Wales already benefit from a more generous capital threshold than in England, this means that the funding available for any planned reform of social care could go further.

At the same time, Wales stands out as one of the areas most affected by the decision to withdraw the Universal Credit uplift.

This reduction in income will be felt particularly acutely as the cost of living bites.

Featured image by Jeremy Segrott, licensed under CC BY 2.0.

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Rugby

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections