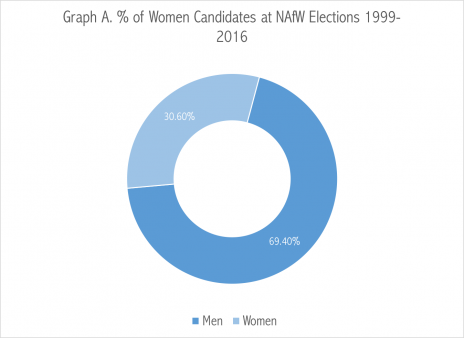

Gender and Representation in National Assembly for Wales Elections

12 October 2016

Breakdown by Party

An analysis of the 5 main parties’ constituency candidates by gender reveals Labour considerably ahead of its competitors in terms of women’s candidacy (indeed running more women candidates than men in 2003 & 2007 races). By contrast the Liberal Democrats flatline around 30% whilst within Plaid and the Conservatives’ men outnumber women 4:1.

UKIP takes the wooden spoon, however, having stood 0 women candidates in 2007 – though some consideration must be given to the fact that they didn’t stand in constituency races in 1999 or 2011, reducing their total cohort of candidates.

By analysing candidacy at regional list level we can gain a closer understanding of what function proportional representation plays in ‘topping up’ a gender deficit. Graph D shows Plaid make considerable improvements through party lists, whilst Labour are again close to gender parity. The Conservatives and UKIP fare particularly badly again, revealing a more profound lack of female candidates. All parties still fall short of 50:50 – suggesting a ‘pipeline problem’ in the movement of women candidates through party structures to selection.

By taking a look at elected Assembly Members, we are able to compare party candidacy across Wales with their ability to secure women’s representation through an effective selection process.

At first glance the Lib Dems display seemingly impressive results across constituency races, but in reality this is more of a reflection of their consistent struggle to win constituency seats (they have only ever elected two women AMs, Kirsty Williams and Jenny Randerson). Similarly, Trish Law single-handedly boosts women’s representation in independent candidacies by winning a by-election and re-election in Blaenau Gwent. However, more generally, just 17.5% of Independent and Minor party candidates are women, suggesting that Trish Law’s accomplishments are outliers from the general trend. Labour are, again, the only party to hit and exceed the 50:50 standard, having elected more women through both constituency and list seats.

Conclusion

The numbers show that Wales’ progress on gender representation relies heavily on one factor: the enduring success of Welsh Labour. Although other parties have made use of proportional representation at the Assembly to effectively ‘top-up’ on women candidates through regional lists, this is not a sustainable means of ensuring balanced representation. Plaid Cymru demonstrate this pattern most strongly, with a low representation at the constituency level that is counterbalanced by progress on the list.

Labour’s achievement too must be cautioned, in that it is reliant on Labour continuing to return a steady number of AMs, despite facing a 7.6% drop in constituency vote share in 2016. Although their continued dominance of the Assembly has enabled the party to enjoy a greater candidate pool and a greater selection of seats to elect women, ERS Cymru’s 2016 report reveals the fragility of even Labour’s progress. If the trend of Labour’s ‘safe’ seats returning male candidates continues in tandem with women incumbents defending battleground constituencies, Labour too may see their progressed dashed by a creeping ‘incumbency overhang.’ The continued dominance of male candidates through every other party – through both constituency and list candidacy – reveals a fragile picture behind the women with a seat in the Senedd.

For Wales to ensure it maintains progress on gender parity – and its reputation as a more representative body than Westminster – it will require every major party to correct for gender imbalance where it exists. Whether this be through through all-women shortlists, twinned constituencies, zipping or another proven method, it’s clear that without a gear-shift women’s representation in the Senedd will be increasingly fragile.

This blog was co-written with Rachel Statham. Rachel is Political Campaigns Coordinator at the Women’s Equality Party and tweets at @rachelstatham_

Comments

3 comments

Comments are closed.

- June 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Rugby

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections

An interesting blog, though I think the conclusions are somewhat skewed by the focus on the whole period 1999-2016, rather than some of the more recent changes in patterns of representation. During my time as Chair and Deputy Chair of Plaid, a majority of women were selected in target constituencies by the party, and that has followed through into the 2016 election result where for the first time Plaid’s female AMs are predominantly constituency ones, not list ones. (To be clear – I don’t make a connection between my positions in the party and the selections (!), rather that as an NEC during that period we specifically monitored this aspect and sought to bring about positive change)

Thanks for the comment Dafydd.

We accept your point that the blog doesn’t discuss positive changes that have been made in recent elections with regards to the gender balance of AMs for each party. We are planning a further blog that will actually look at how competitive constituency seats are in places where women are challenging or incumbents, as well as their positioning on party lists that will hopefully illuminate some of the points you raised.

However, we feel that the central point of the article – that parties need to take action on this issue – stands. At the constituency level, Plaid have never fought a NAfW election where more than 25% of its candidates have been women, and the proportion of women candidates on the list has actually been in decline since 2003. Of course, this isn’t to say that progress hasn’t been made in other areas, but in terms of overall proportion of women candidates, this has been limited.

Again we appreciate the comment and hope to provide more insight on the points you raised in the future.

J&R

This is a good summary with some useful graphs and tables, Jac and Rachel. I have long argued the same, ie reliance on Labour dominance electorally (maintenance of respectable gender figures were ‘saved by the bell’ in both 2011 and 2016) and the stability of candidate selection/reselection (much of which depends on ‘incumbency overhang’ as we highlighted in the ERS report). It’s not as straightforward as a supply and demand pipe line issue might suggest either as women are more likely to be selected to fight marginals or be placed on a list in a vulnerable second or third position.

My conceptual analysis is of this focuses on the remarkable lack of real cultural buy in as to the real electoral and political value of diversity in any of the main parties. Labour fares best in this regard (and can be attributed to critical mass, the politics of presence and the fact that most of its initial AMs were equality champions and feminists). The other parties range from ‘imitators’ to ‘laggards’ in truth, and there remains a lack of real drive and leadership around this important issue in my opinion.