Cut to the bone? How a decade of austerity has left its mark on local government in Wales

12 February 2019This post draws on work from a recently published report into local government finance by Guto Ifan and Cian Sion from the Wales Fiscal Analysis team: Cut to the bone? An analysis of Local Government finances in Wales, 2009-10 to 2017-18 and the outlook to 2023-24.

As local authorities across Wales prepare to publish their budgets for 2019-20, expect to see a significant rise in Council Tax, with councils increasingly relying on locally-sourced revenue to partially offset cuts to their funding and to meet increasing demand pressures.

In Part 1 of this two-part series examining local government finance in Wales, we look at trends in revenue and spending over nearly a decade of austerity.[1]

A shift towards local taxation

Local government in Wales is primarily funded via grants and redistributed business rate revenues from the Welsh Government. The Welsh Government budget for day-to-day spending has fallen by 5.3% in real terms since 2009-10. Since 2013-14, the share of this budget allocated to local government has also been falling, from 39.1% to 35.5%.

The value of Welsh Government grants to local authorities fell by £918.5 million (18.8%) in real terms between 2009-10 and 2017-18, a decrease of £340 per person.

The Welsh Government’s policy decision not to freeze or cap Council Tax increases, as was done in Scotland and in England, allowed greater freedom for Welsh local authorities to offset reductions in grant funding to avoid deeper cuts to spending. However, this meant that Council Tax grew at a faster rate on this side of the border.[2]

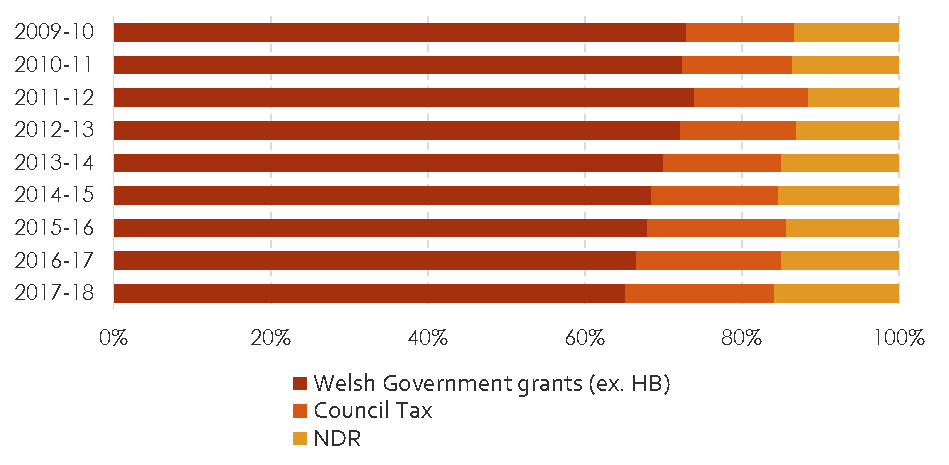

Council Tax revenues in Wales have grown by 22.6% in real terms, accounting for 19% of local authorities’ total gross revenue in 2017-18, up from 13.8% in 2009-10 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Composition of local government gross revenue, 2009-10 to 2017-18 (2018-19 prices)[3]

The overarching trend in Welsh fiscal policy over the last decade has been a shift towards local taxation.

This may not be welcome news. It is well-documented that Council Tax rates are regressive relative to its base – the higher the property value, the less is paid in Council Tax as a share of that property’s value.

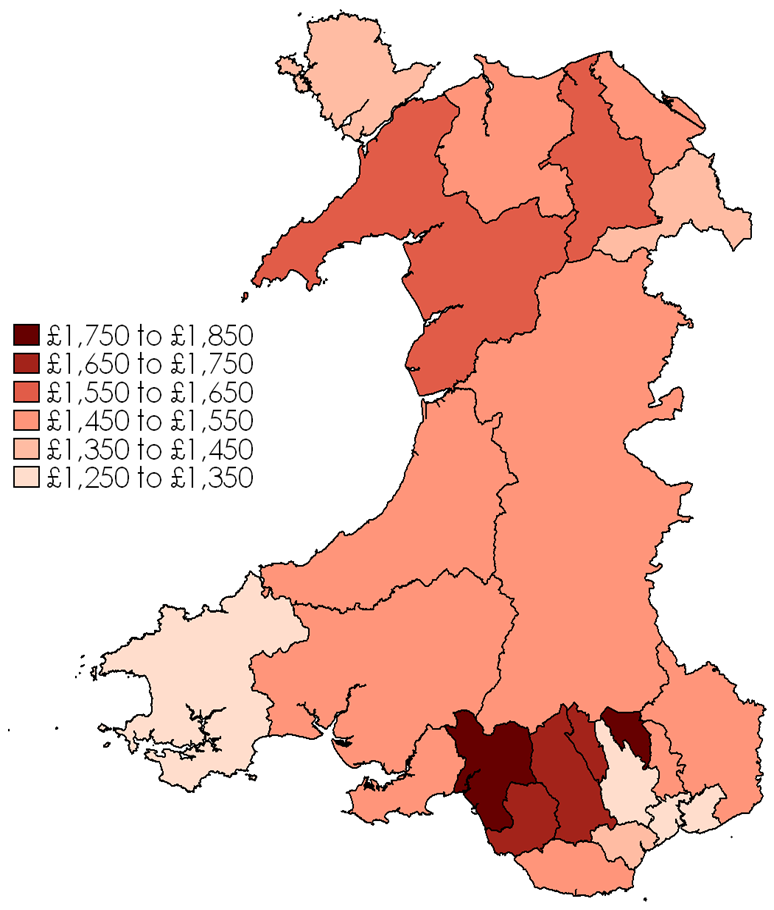

Furthermore, more deprived local authorities, with a higher concentration of properties in the lower bands tend to have higher band D council tax levels (Figure 2). This means, in effect, that the Council Tax burden is unevenly shouldered across local authorities. For instance, in 2017-18 a band B property in Blaenau Gwent paid £1,364 in Council Tax while the bill for a band E property in Pembrokeshire was set at £1,379, only £15 dearer.

As Council Tax becomes an ever more important component of local government financing, issues around its fairness and appropriateness as a tool for funding local services become increasingly salient.

Figure 2: Band D Council Tax levels, 2018-19

A decade of downsizing

Despite growth in Council Tax receipts, local authorities saw a £577m (8.3%) cut in their revenue between 2009-10 and 2017-18. In response, they have resorted to cutting spending on local services.

Local authority spending on services fell by £232 or 10.4% per head between 2009-10 and 2017-18.

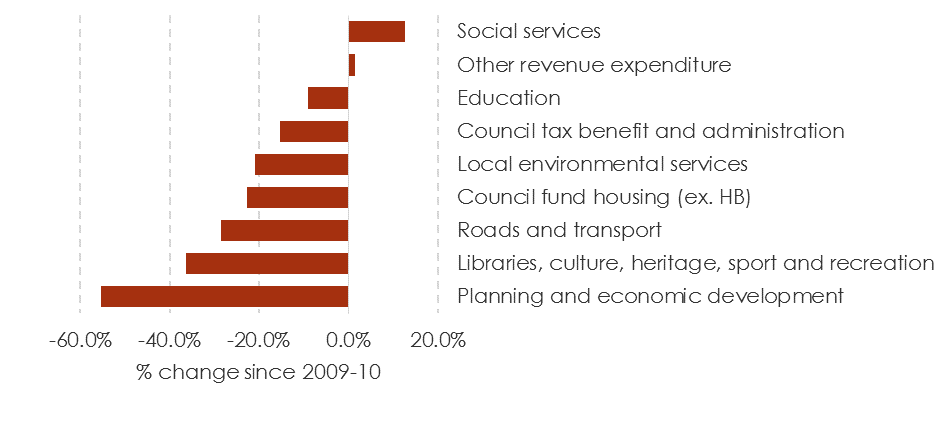

The picture varies significantly across local government departments. Since 2009-10, expenditure on social services (excluding the Flying Start programme) has increased by £106.4m (6.5%) in real terms. This means that social services and education spending now account for 73% of total service expenditure, up from 68% in 2009-10.

However, during the same period there have been large cuts to other spending areas, including planning and economic development (55.4%), libraries, culture, heritage, sport and recreation (36.3%) and roads and transport (28.5%), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Percentage change in service spending, by local authority service area, between 2009-10 and 2017-18 (2018-19 prices) [4]

These cuts have been accompanied by significant job losses. 37,000 local government jobs were lost between December 2009 and September 2018, equivalent to 19.9% of the total workforce size.[5]

This is less than the reduction to the workforce size in England (32.4%) and Scotland (20.6%) but the figure is still significantly more than the combined workforce of Tata Steel, Admiral, Airbus, Transport for Wales, Ford, S.A. Brain and the Principality Building Society.[6]

Growing demand for social services

The real-terms increase in spending on social services partly reflects the priorities and commitment made by successive Welsh Governments, as well as local authorities’ prioritisation of these services in successive budget rounds. However, it is also an indicator of increased demand.

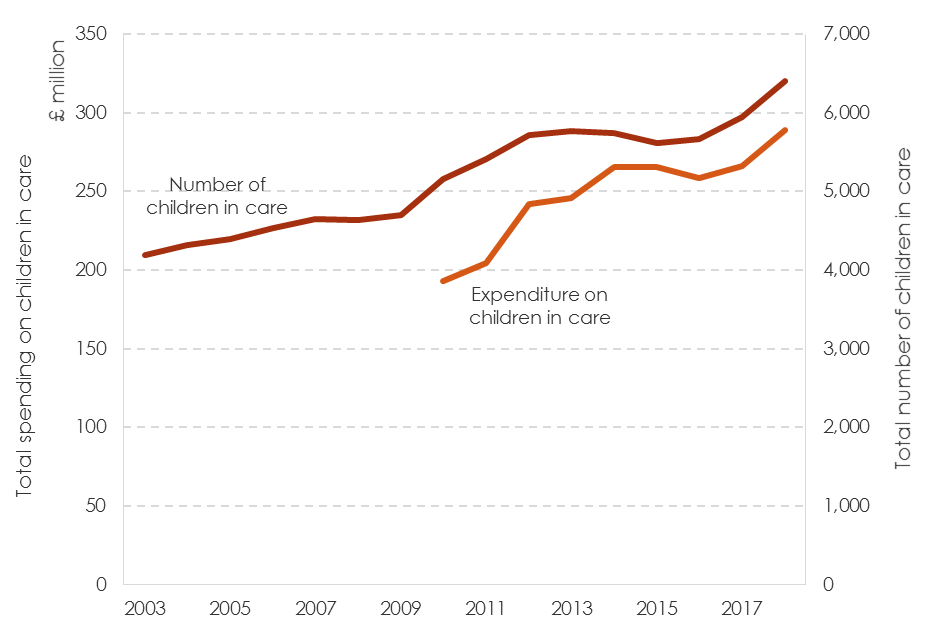

Spending on children in care has increased by £95.9 million (33.2%) in real terms since 2009-10. At the same time, the number of children in local authority care has risen by 1,710 (36.4%).

Figure 4: Total expenditure on children in care and number of children in care across Wales, 2009-10 to 2017-18 (2018-19 prices)

Source: StatsWales (2017-18 and previous) Net Current Expenditure, by local authority and service

The sharp increase in the number of children in care from 2009-10 onwards coincides with a period of welfare reforms and cuts to spending on preventative services.

To put these figures in context, the rate of children in care in Wales now stands at 102 per 10,000, significantly higher than the rate in England which is 64 per 10,000.[7]

Spending on older adults’ (over 65) social care fell by 1.3% in real terms between 2009-10 and 2017-18. However, demand has markedly increased during this period, putting downward pressure on the per capita figure. On a per capita basis, spending on older adults’ social services fell by £157 (-14.8%).

Wales’ aging population will continue to play a key role in driving demand for social services. Conwy already has a higher share of the population over 65 (27.2%) than Japan, the country that tops the world ranking on this measure. However, when examining the challenges associated with funding social care, we must investigate both demographic-related pressures and non-demographic ones.

Conclusion

Increases in Council Tax levels have only partially offset cuts to local government grants. Local authorities have resorted to making extensive cuts to service spending, especially in areas outside of social services and education, leaving local taxpayers essentially paying more money for fewer services. After a near decade of austerity, it is difficult to gauge how much further attrition some local government services can face before they become unsustainable.

In Part 2, we explore the future prospects for local government finance and offer revenue projections for the next five year period.

Notes

[1] The revenue and spending data cited in this post has been sourced from the Outturn and Financing of Gross Revenue Expenditure tables published by StatsWales for the years 2009-10 to 2017-18.

[2] Although Council Tax levels in Wales remain lower than in England, the gap has narrowed in recent years. In 2009-10, the headline Band D rate was £277 higher in England than in Wales. By 2017-18, this figure had fallen to £171.

[3] Council Tax and gross revenue figures are calculated net of the Council Tax Reduction Scheme, which is paid to people on low incomes and/or certain welfare benefits to help with council tax bills.

[4] The change in social services and education spending is somewhat exaggerated in this graph due to the Flying Start element being removed from the education category and re-classified as social services spending in 2013-14.

[5] Dataset was produced by the Office for National Statistics on request and is available here.

[6] https://cymru-wales.unison.org.uk/tag/audit-of-austerity/

[7] The rate of looked-after children in England is sourced from a recent report by the National Audit Office: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/pressures-on-childrens-social-care/

Comments

- June 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Rugby

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections

1 comment

Comments are closed.