Covid-19 and the economic challenges facing the incoming Welsh Government – part 2

20 May 2021In this series of blog posts, Jesús Rodríguez from the Wales Fiscal Analysis (WFA) team explores the economic challenges facing the incoming Welsh Government in recovering from Covid-19. Part 1 can be found here.

The impact of Covid-19 on the Welsh labour market

As expected, given the magnitude of the economic recession, the Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant effect on the Welsh labour market, though this has been tempered by government support schemes.

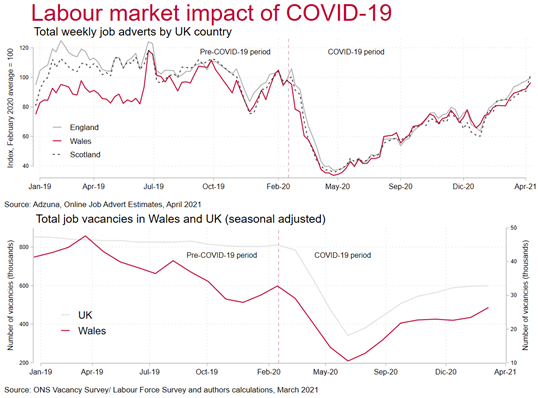

Figure 1 depicts two measures of the demand for labour – weekly job adverts over time and the number of vacancies – which illustrate the extent labour markets have responded to the crisis. There was a sharp decline in the total weekly job adverts in Wales at the onset of the crisis, falling to a third of pre-pandemic averages in May 2020. The series has since increased steadily. The number of vacancies fell by a similar magnitude (68%) between February and June 2020. In March 2021, vacancies had recovered to around 80% of pre-pandemic levels.

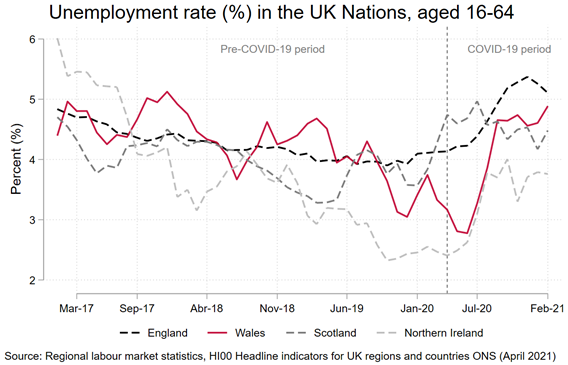

In Wales, the unemployment rate among those aged between 16 and 64 had been gradually falling since around 2011, reaching the historically low level of 2.8% in 2020. It has subsequently increased to 4.9% during December to February 2021. This is below the level in England and remains low in comparison to the peak seen after the global financial crisis of 2007-08.

Figure 1

Figure 2

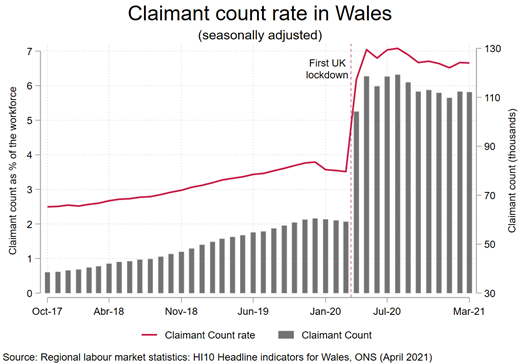

On the other hand, the claimant count in Wales – reflecting those claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance or Universal Credit and currently ‘searching for work’ – showed a huge rise (101% from 59,000 in March 2020 to 119,200 in August 2020. This surpassed the levels reached after the 2007-08 global financial crisis. However, this measure overstates the true increase in unemployment and is likely to include many people still working, furloughed or in receipt of the self-employed income support (Brewer et al., 2020).

Figure 3

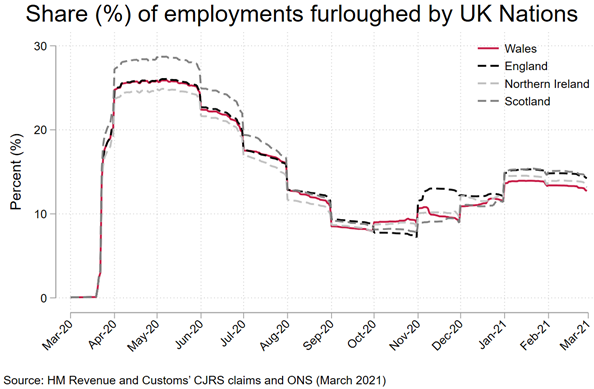

One of the reasons for the subdued effect of the crisis on unemployment figures thus far has been the role of government support, which has supported employment and incomes during the crisis. Since March 2020, over 463,000 employments have been furloughed in Wales. This amounts to 35.9% of the eligible workforce, though take-up rates vary significantly across the country, from 41.3% in Gwynedd to 31.3% in Neath.

As shown in Figure 4, the share of furloughed employments increased from September 2020, but remained below the initial levels seen in April and May 2020. The latest official data from HMRC (2021) showed 159,600 employments still furloughed by the end of March 2021, which amounts to 12.7% of the eligible workforce (slightly below the UK average of 14.3%).

Figure 4

The ending of the furlough scheme, planned for the end of September 2021 will be an important milestone for the Welsh labour market. There is scope for a significant increase in unemployment unless the economy and labour demand rebounds strongly. If Welsh unemployment follows the path of the OBR’s (2021) forecast for unemployment at a UK level, then the unemployment rate would peak at around 6.0% towards the end of 2021, before recovering to pre-Covid-19 levels in the second quarter of 2023.

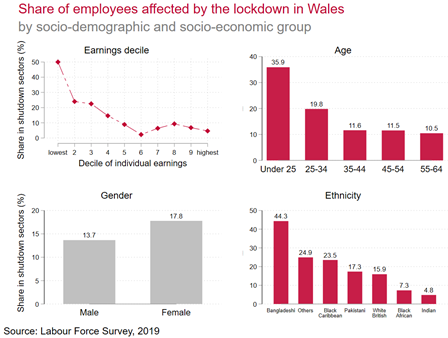

One particular concern will be the unequal impact of the crisis (Rodríguez, 2020). Workers under the age of 25 were almost three times as likely to have been working in shutdown sectors. Fully half of the lowest-earning decile of Welsh workers were in shutdown sectors of the economy – making them ten times as likely to have been affected by the shutdown compared with the highest-earning decile. This asymmetric impact makes it likely that Covid-19 will exacerbate existing inequalities.

Figure 5

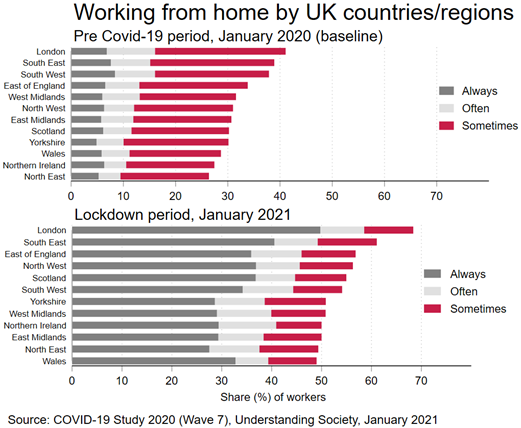

Higher earners were also more likely to be able to work from home during the pandemic. According to longitudinal data, 33% of Welsh workers were always working from home in January 2021, with another 7% doing so often and 10% doing so sometimes. This level of homeworking represents a significant shift away from pre-crisis working patterns and has been sustained during the last year.

Figure 6

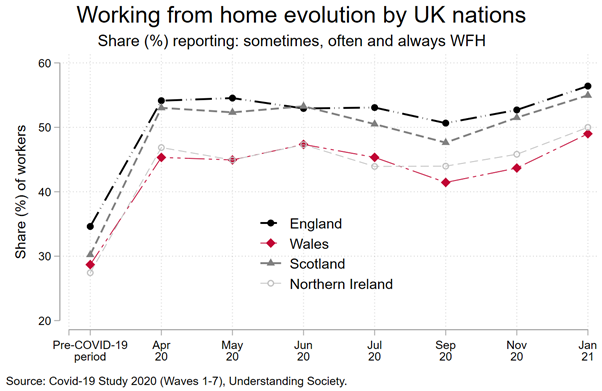

Based on an assessment of the feasibility of working from home across different jobs, one study finds that Wales was the UK nation with the lowest potential share of jobs that can be done from home (Rodríguez, 2020). This pattern was consistently recorded throughout the entire pandemic, Figure 7 shows the evolution of working from home since the start of the coronavirus crisis. On average, 45% of Welsh workers reported having been working from home during the COVID-19 period, while in the rest of the UK this figure rises to 50%.

Figure 7

The Welsh Government (2020) have announced a ‘long-term ambition to see around 30% of Welsh workers working from home or near home’, which may have significant implications for productivity, towns and urban centres, and public services (Carter and Johnson 2021).

The economic challenges facing the new Welsh Government

The 30 seats won by the Welsh Labour party at the Senedd election on 6 May allowed it to form a government on its own (BBC News 2021). Its manifesto promised continuity in terms of policies, little in terms of new specific spending programmes, and a focus on Covid-19 recovery (Wales Fiscal Analysis 2021).

Additional spending by the UK government in England led to huge amounts of additional funding for the Welsh Government, as the day-to-day spending budget grew by approximately 30% (or £5.2 billion) over 2020-21. Alongside UK government support for the Welsh economy, the Welsh Government has been responsible for providing significant support for businesses in Wales through the crisis (Economic Intelligence Wales 2020).

Lower costs for PPE and the devolved element of the test and trace system in Wales allowed a greater share of spending on business grants and reliefs in Wales (Ifan 2021). The Welsh Government has approximately £2.5 billion of Covid-19 funding for its pandemic response in 2021-22. Non-domestic (business) rates and further grant support for businesses has been among the allocations made thus far (Welsh Government 2021).

Supporting the recovery and dealing with the economic legacy of Covid-19 will require sustained additional investment from the Welsh budget. Arguably, the most significant commitment in the Welsh Labour manifesto was the promise of a new Young Persons Guarantee, which would give everyone under 25 the offer of work, education, training, or self-employment. This will require further spending on skills and employment policies, which are budgeted at £194 million this year.

The Welsh Government will also need to be mindful of new UK Government schemes which will operate in Wales – for example, Kickstart (which will fund six-month placements for 16-24-year-olds on Universal Credit) and Restart (supporting Universal Credit claimants to find jobs in their area). Simplified and joined-up support for those who need it will be important. Additional efforts will have to be made on issues regarding wage progression and the creation of good jobs for lower educated workers, which has become a key issue for the post-covid labour market inequality.

Finding sufficient funding for programmes from the Welsh Government budget will also be a challenge. Previous devolved interventions in this field – such as the React and Proact schemes introduced in 2008 – had often been part-funded by EU funding, which will no longer be available.

There are also other huge pressures elsewhere in the Welsh budget. Post-pandemic pressures are likely to come from many directions, including the cost of reducing the backlog in elective care in the NHS (Ifan 2021) and the need for additional learning provision for students (Education Policy Institute 2021)

Current UK government spending plans contain no Covid-19 funding after 2021-22, assume NHS and schools spending in England return to pre-pandemic multi-year plans, and imply cuts for other public services (Zaranko 2021).

Since Welsh Government funding mainly depends on UK government spending plans in England, this implies a relatively austere outlook for the Welsh budget. Balancing competing demands in recovering from Covid-19 will be a huge challenge over the next Senedd term.

Data and replication files for this blog can be found here.

Comments

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- December 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Reform UK

- Rugby

- Senedd

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections

1 comment

Comments are closed.