Innovation breeds innovation: from violence prevention to the UK What Works Council

26 October 2018

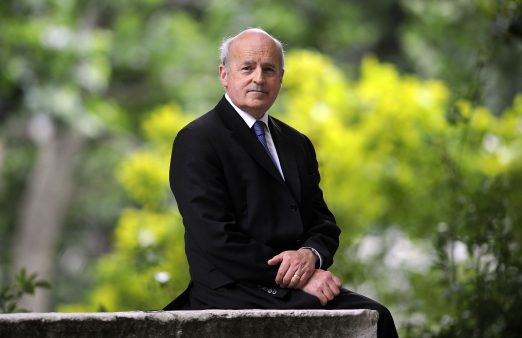

Author: Professor Jonathan Shepherd

In July 1997 I took the plunge. My research had told me years previously that hospital A&Es are sources of unique data about violence which could be used to drive better targeted policing. The implication was that violence could be prevented more effectively if data from A&Es and police were pooled and if executives from policing, health and local government got together regularly to use it to identify and then tackle violence hotspots and weapon availability.

The step into the unknown in question, delayed by the graft involved with rejuvenating a run-down university department, recruiting many staff, establishing my NHS practice and starting two new research groups, was to call the meeting which spawned Cardiff’s multiagency Violence Prevention Board. I was hugely encouraged by the willingness of those invited, a South Wales Police inspector, County Council official and Victim Support co-coordinator, to meet – and to meet again.

Testing and refining

As with all innovations, the effectiveness and cost benefit of this new Cardiff partnership needed to be tested in rigorous trials. If it didn’t reduce violence relative to cities without such partnerships then it would just be a waste of resources, and would divert busy professionals from strategies which were known to be effective. Supported to start with by a substantial Home Office grant, evaluation began to show that this new approach worked.

Not for the first time I learnt that innovation needs to be nurtured, refined, documented and persisted with. Theory wasn’t enough; success only came with close attention to the nuts and bolts. Ways of collecting information in A&Es about precise violence locations, weapons and assailants needed to be found and evaluated; new A&E software needed to be written and embedded in the existing IT system; data analysts and evaluators needed to be recruited; administrative support needed to be found.

Some seemingly effective interventions just didn’t work and were ditched; encouraging injured people to access victim support services, and increasing the chances of offenders being brought to justice for example. This approach was copied on Merseyside and in Glasgow, examples of Cardiff Model early adopters together with the first implementation of the Model overseas, in Amsterdam.

The Cardiff Model

It was only after 40 meetings of the Board over five years that convincing evidence of effectiveness was published. But great encouragement soon followed; in 2007 it was clear from injury data that Cardiff had become the safest city in its Home Office designated family of 14 “most similar” cities. In 2008, the then government included the Cardiff Model in its revised alcohol strategy. In 2010 the new coalition administration made it a commitment in its programme for government.

By the early 2000s, reflecting on the Cardiff Board, I had been puzzling over why it was that whereas my background was in clinical schools in Russell Group universities whose research is funded by the Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health research, there were no equivalent opportunities in policing or, come to that, probation. Other public services seemed to be evidence deserts compared with healthcare. And why was it that the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guided the NHS but there were no similar organisations publishing evidence based guidance on crime prevention, education or local government?

Diving into a different pool

Encouraged by the success of Cardiff’s violence prevention innovation, if a little intimidated by the thought of another 10 years work before fruit was borne, I dived into a different pool. In 2010, Sir Adrian Smith FRS, a former president of the Royal Statistical Society, was director general at the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS). I wrote to him to highlight these anomalies and to recommend that NICE equivalents should be formed to support all major public services and that representatives of each of these new entities should meet in a new national board in which expertise on the generation, synthesis and mobilisation of evidence would be shared.

He replied very positively and asked to meet. He subsequently introduced me to the then director of the Institute for Government (IfG), Sir Michael, now Lord, Bichard – a former permanent secretary at the Department for Education. A second meeting took place at the IfG, also attended by David Halpern the IfG’s research director. As a result, the IfG organised a round table conference which was chaired by the then science minister, David Willetts.

At this conference, which I was privileged to open, these recommendations found favour. As with the violence prevention board, it took time and many more meetings before the form and function of what became the UK’s What Works Centres were settled. There are now eight such centres, each with responsibility for evidence synthesis and guideline production in a particular sector. The concept of the new national board crystallised into what is now the What Works Council, administered by the UK Cabinet Office. Former Cabinet Secretary, Sir Jeremy Heywood is a keen supporter. The Wales Centre for Public Policy, ably directed by the University’s Professor Steve Martin, is an associate Council member.

A guiding star

To take one example, the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), the designated What Works Centre for Education has now funded more than 100 randomised policy trials, including of interventions designed to improve literacy and to make best use of teaching assistants. EEF incorporates this evidence, so important in the context of the fad and fashion which have bedeviled education over the years, in its authoritative and accessible guidance for teachers, parents and tax payers. In the same way that NICE guides health professionals, patients and the NHS, so the EEF has become a guiding star in education.

Professor Jonathan Shepherd is the independent member of the What Works Council and represents the Academy of Medical Sciences on the Home Office Science Advisory Council. He is based at the University’s Crime and Security Research Institute which he co-founded in 2015. He chaired the Cardiff Violence Prevention Board from 1997 to 2017.