The Use of Japanese Tissue Paper in the Conservation of Natural History Specimens: The In-filling and Re-furring of a Taxidermy Atlantic Grey Seal Pup

19 January 2022Last October, during the first class of my first year of the Conservation Practice MSc at Cardiff University, I expressed an interest in natural history collections. The result was being allocated a taxidermy Atlantic Grey Seal pup (Fig.1) from Tenby Museum as my first object. Looking through the object documents, I found that the specimen had previously been conservation cleaned by a past student. The seal has structural damage to his muzzle, loss of fur on spots of his pelt, and broken claws. However, the previous student (you can read her blog answering taxidermy FAQs here) hadn’t had a chance to treat these further issues. In the object notes, they expressed the possibility of treating the holes in the seal’s skin and inner mount with Japanese tissue paper. This acted as a jumping off point for me and initiated my research into the use of this versatile material, traditionally used in paper and book conservation, to treat natural history specimens, and how I could use it to treat my object.

So, what is Japanese tissue and how can it be used in the conservation of natural history specimens?

What is Japanese Tissue Paper?

Japanese tissue paper is formed from plant fibres – primarily the bark of Kozo, Gampi or Mitsumata. The natural strength and length of these plant fibres, in conjunction with the process of manufacturing the tissue, results in large sheets of strong, thin, and flexible acid-free paper which can vary in grades and weights, making this material incredibly versatile in its uses for conservation.

Due to its properties, Japanese tissue has been used for object conservation for hundreds of years. Principally, it has been used in paper conservation but also in that of wooden objects, artworks, and textiles.

It is often used with an adhesive for repairing tears, backing and facing materials, and also gap-filling. The work you are doing will determine the type, weight, and grade of the paper and the adhesive used. Generally, the heavier weighted the paper, the stronger the repair. A variety of adhesives can be used with Japanese tissue. Traditionally, wheat starch paste, but many other reversible adhesives, including but not limited to PVA (polyvinyl alcohol), PVAc (polyvinyl acetate), Paraloid B72, and methyl cellulose have been used successfully.

The paper can also be dyed or toned prior to use for treatment, and can also be in-painted with pigments, using acrylics, watercolours, or gouache, for example.

How can Japanese tissue paper and adhesive be used to treat natural history specimens?

Firstly, Japanese tissue can be used as a gap-fill to repair tears in the skin of natural history objects. Splitting of skin is particularly rife in natural history specimens, as the proteins in the skin can change chemically in the preservation process, cross-linking and leaving it vulnerable to damage from fluctuations in the environment. One such fluctuation can be that of Relative Humidity (RH). A low RH can cause embrittlement of the skin, particularly around the vulnerable areas (such as the face), which can lead to splitting. Strips of tissue can be used with an adhesive to form a replacement skin and repair the resulting tears before being in-painted if required.

The material can be also used to reinforce joins on objects. As Japanese tissue retains its structure when wetted or saturated with adhesive, it strengthens adhesive joins made on damaged specimens, including objects such as shells, birds and fish. These joins do not have to be purely between protein-structured materials but can be used to reattach body parts formed from materials such as rubber, for example.

As well as reinforcing joins, tissue can also be used to support delicate areas of specimens such as the feathers on birds, wings of insects, and fins of fish. Applying strips of tissue with an adhesive can produce a strong but also effective aesthetic result.

The Natural History Museum demonstrates how the material can also be used to strengthen weak or brittle areas of specimens with a giant oarfish. The delicate bones of the specimen were strengthened with tissue and adhesive to prevent further damage.

The final method of usage that we will consider in this brief outline is the creation of ‘fur’ patches made from tissue. This is further discussed below but is essentially when the feathered edges of Japanese tissue replicate the fur of the object you are conserving, enabling you to treat loss of hair from a pelt.

Experimentation and an Atlantic Grey Seal pup

My taxidermy seal has seen better days. He entered the care of Cardiff University with other natural history specimens from Tenby Museum which had been damaged by an infestation of carpet beetles. As such, he has some of the typical damage such as holes in his pelt.

In Fig.3 you can see the splitting of the embrittled skin on one side and the exposed and crumbling inner mount (identified through SEM to be made of clay) on the other.

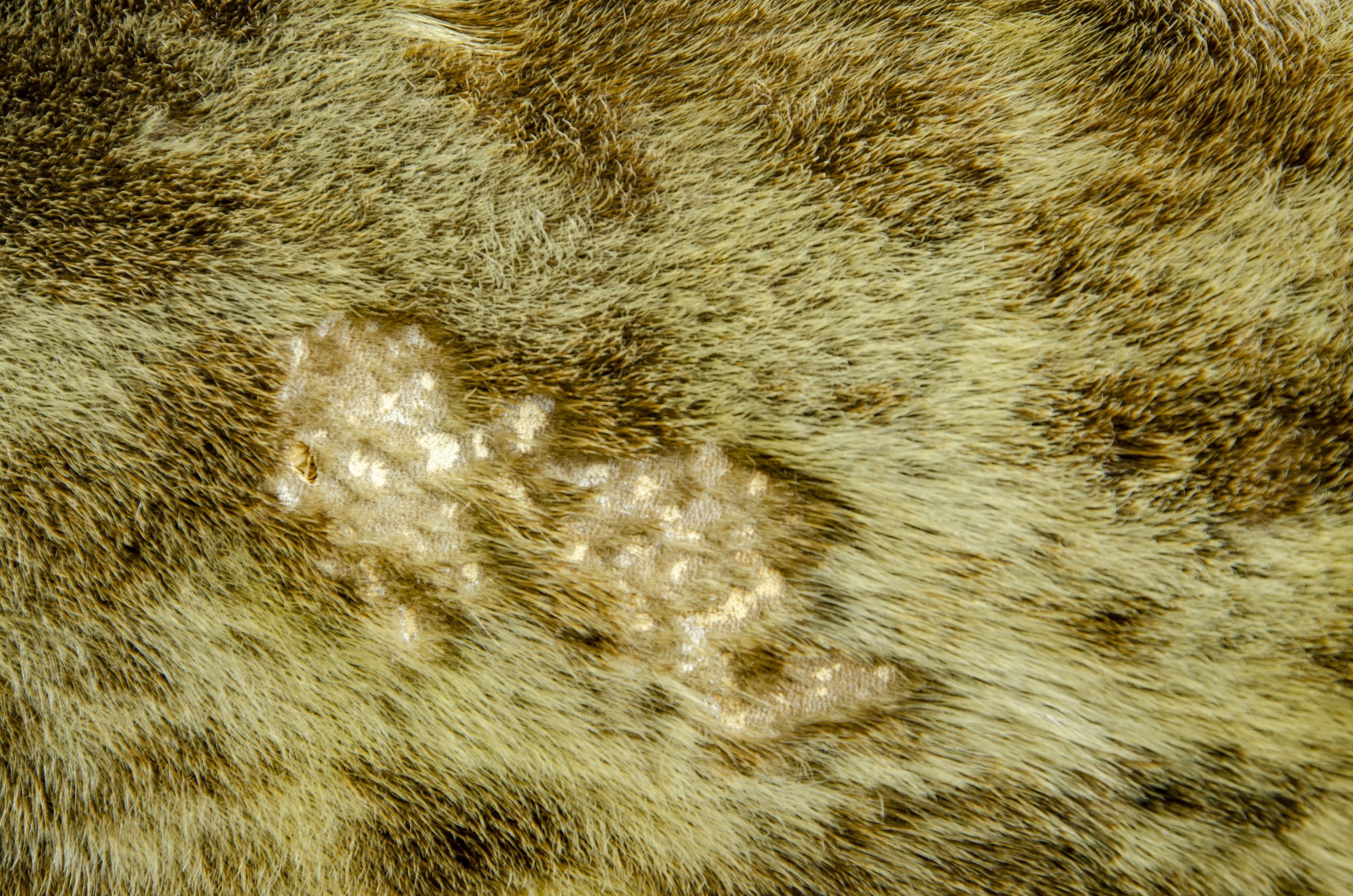

You can see below where he has suffered from a loss of fur on his pelt (Fig.4) and where several claws have broken off (Fig.3).

Japanese tissue can be utilised to treat this object in a variety of ways due to the multiple areas of damage.

My initial idea for using this material was in the gap-fill the exposed mount and split in the muzzle skin. Currently in the lab we have 6gsm and 12.2gsm paper – due to its thickness and strength I am experimenting with the 12.2gsm Tosa-Kozo tissue. I am looking to create a gap-fill using strips of this with the adhesive methyl cellulose. I have decided on methyl cellulose for my initial attempts due to its reversibility, flexibility, and success in use by other conservators for treating skin loss in taxidermy specimens. When somewhat dry, but still malleable, I hope to texturize the outer layer of the fill – this could be done with a scalpel or other sharp-edged tools. As the object is being conserved for display purposes, I will also consider methods of toning the paper and in-painting the fill. I will look at using acrylics or gouache, amongst other paints and pigments, to determine the best course of action.

I possess some detached fragments from the muzzle were bagged and stored with the object (Fig.5). As these are of usable size, I will reattach these on top of the gap fill. Due to the malleability of the Japanese tissue and methyl cellulose fill, I should be able to manipulate the surface to get a good and accurate join on these fragments.

I will also investigate reinforcing the adhesive joins with tissue when reattaching the broken claws.

My final idea came from this blog post, in which conservator Charlotte Ridley used tissue with wheat starch paste to create a patch of ‘fur’ for a jaguar’s ears. I have already actively been experimenting with this method. Again using 12.2gsm tissue with methyl cellulose, I water-cut the paper to form the base layer for the patch (this ‘feathers’ the edge, allowing for better hold on the object and an invisible edge) (Fig.6). I repeated this with another layer and fixed this with the adhesive to reinforce the base.

I then water-cut strips, about 15mm in width, the same length as the original patch. I further feathered the edges of these strips by teasing the edges with my fingers and using a pair of tweezers and a dental tool. Folding these in half, I attached the strips to the base layer along the fold, ensuring that the base layer and folded edge were saturated in fresh adhesive. This process was repeated until a patch had been formed (see Fig.6-9).

I will continue to experiment using this method to find a suitable tissue grade and adhesive to create a patch with a suitable density and appearance for the seal’s pelt.

I will consider options for colour-matching the fur both after the patch is formed but also in toning the paper prior constructing them. The images below show the beginning of this, where I quickly coated the tissue with a diluted acrylic paint to see how it affected the texture and structure of the paper (Fig.10).

Hopefully in due course I will settle on a preferred method of treating my object. While the adhesive and method specifics may inevitably change, I will be using Japanese tissue in some capacity in my treatments.

I hope that this may have been useful for you in demonstrating the material and how you can use it to treat your natural history specimens – particularly if you, like me, are unexpectedly given the care of a taxidermy seal.

All images are Author’s own.

References

Amnhconservator (2017) ‘Case Study: Lemur mount treatment part 2: treatment’, In Their True Colours, 16th January. Available at: https://intheirtruecolors.wordpress.com/2017/01/16/case-study-lemur-mount-treatment-part-2-treatment/ [Accessed on 5th January 2022]

Artal-Isbrand, P. (2017) ‘So delicate, yet so strong and versatile: the use of paper in objects conservation’. Objects Specialty Group Postprints, 24. pp.168-187.

Berry, E. (2020) ‘Frequently asked questions in taxidermy’, CU Conservation Blog (12th March). Available at: https://blogs.cardiff.ac.uk/conservation/frequently-asked-questions-in-taxidermy/ [Accessed on 5th December 2021].

Fine Art Restoration Co. (2021) ‘Looking after taxidermy: how to protect natural history’. Available at: https://fineart-restoration.co.uk/news/looking-after-taxidermy-how-to-protect-natural-history/ [Accessed on 21st December 2021].

Fukuda, S. (2014) ‘Japanese papers revisited’, ICON News, The Magazine of the Institute of Conservation, 51. p.20.

Glennon, E. (2017) ‘Taxidermy conservation with Simon Moore’, Glennon Diorama, (12th May). Available at: https://glennondiorama.wordpress.com/tag/taxidermy/ [Accessed 12th January 2022].

Graham, L. (2014) ‘A different approach for treating skin loss on taxidermy’. In J. Bridgland (Ed.) ICOM-CC 17th Triennial Conference Preprints, Melbourne, 15 – 19 September 2014, 1201. Paris: International Council of Museums. 1-8.

History New England (2017) In conservation, Japanese tissue is a magic material. Available at: https://www.historicnewengland.org/magic-material-japanese-tissue-conservation-lab-2/ [Accessed on 14th January 2022].

Kaminitz, M. and Levinsion, J. (1989) ‘The conservation of ethnographic skin objects at the American Museum of Natural History’, Leather Conservation News. 1. Pp.1-7.

Larkin, N. R. (2016) ‘Japanese tissue paper and its use in osteological conservations’. Journal of Natural Science Collections. 3. pp.62-37.

Megumi Mizumura, Takamasa Kubo and Takao Moriki (2015) ‘Japanese paper: History, development and use in Western paper conservation’, Adapt & Evolve: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015. pp.43–59.

Moore, S. J. (2007) ‘Japanese Tissues: uses in repairing natural science specimens’, Collections Forum. 21(1). Pp.126-132.

Murphy, B and Rempel, S. (1985) ‘A study of the quality of Japanese papers used in conservation’, The American Institute for Conservation, 26. pp. 1-13.

National Park Service (2019) Martin Itjen curiosities. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/klgo-itjen-curiosities.htm [Accessed on 14th January 2022].

Natural History Museum (2021), Caring for specimens at the museum. Available at: https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/caring-for-specimens-at-the-museum.html [Accessed on: 11th December 2021].

O’Brien, C. (2019) ‘Japanese Tissue’. Quarto Conservation (8th April). Available at: https://www.quartoconservation.com/post/japanese-tissue [Accessed on 14th January 2022].

Philp, J. (2020) ‘Nip and Tuck’, The University of Sydney, (2nd September). Available at: https://www.sydney.edu.au/museum/news/2020/09/02/nip-and-tuck.html [Accessed on 12th January 2022].

Ridley, C. (2017) ‘Conserving with Japanese tissue: beyond books and paper, part 2’, The Book and Paper Gathering (6th April). Available at: https://thebookandpapergathering.org/2017/04/20/conserving-with-japanese-tissue-beyond-books-and-paper-part-2/ [Accessed on: 14th November 2021].

Ritchie, F. 2013. The Investigation and Conservation Treatment of a Mounted Orangutang. Buffalo State University: M.A. Dissertation. (Unpublished).

Sirett, C. (2017) ‘Conserving a Legend: The bison head mount’, Manitoba Museum (2nd August). Available at: https://manitobamuseum.ca/conserving-a-legend-the-bison-head-mount/ [Accessed on 14th January 2022].

Soleymany, S., Ireland, T. and McNevin, D. (2015) ‘Toning Japanese tissue papers: An international survey of paper conservation practitioners’. AICCM Bulletin, 32.2. pp.116-123.

Suarez Ferreira, R. (2019) ‘Unfolding the Lennox-Boyd fan collection – part 2’, The Fitzwilliam Museum (2nd March). Available at: https://blogs.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/conservation/tag/fans-lennox-boyd/. [Accessed on 14th January 2022].

Suzielwp (2015) ‘Pseudo skins – creating synthetic skins for areas of loss in taxidermy’, A Girl and Her Stuffed Squirrel (4th March). Available at: https://agirlandherstuffedsquirrel.wordpress.com/category/taxidermy/ [Accessed on 14th January 2022].

Wills, B (2002) ‘Toning paper as a repair material: its application to three-dimensional organic objects’, The Paper Conservator. 2(1). pp. 27-36.

- March 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (6)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (8)

- March 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (3)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (4)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (5)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (2)

- March 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- August 2018 (2)

- July 2018 (5)

- June 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (3)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (3)

- May 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (4)