Frequently Asked Questions in Taxidermy

12 March 2020

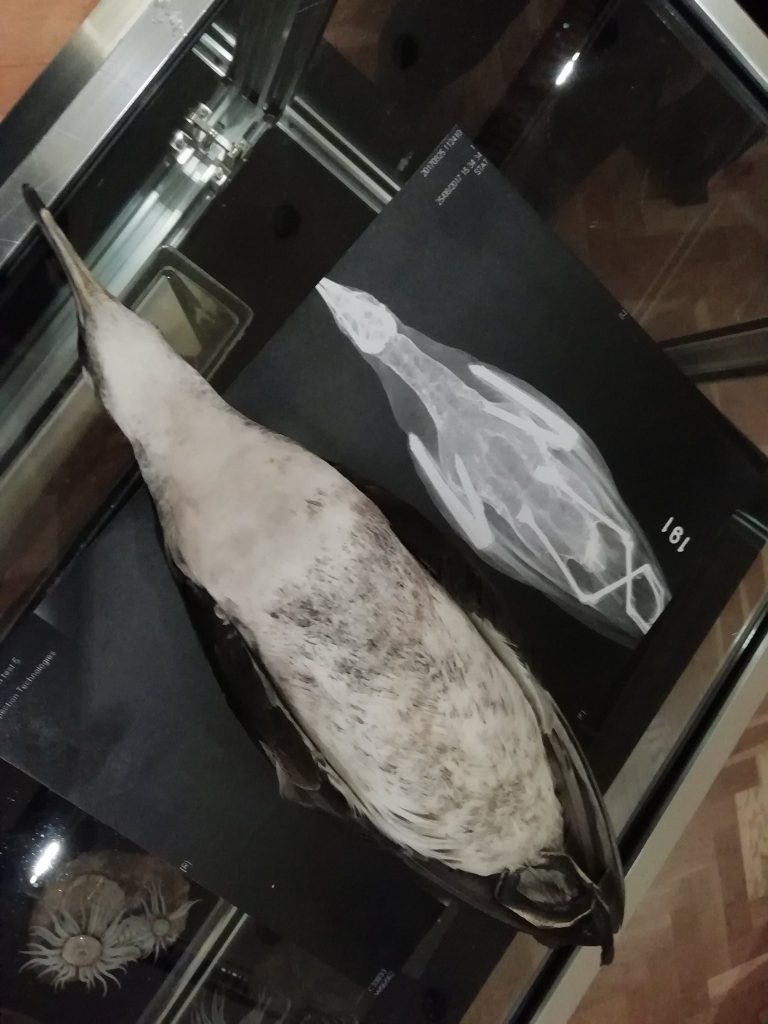

I recently helped out at the National Museum of Wales’ (NMW) After Dark event held on the 19th of February. It was a really fun event, with a great turnout of 852 curious visitors coming to peruse the halls. The art conservators and the natural history conservators collaborated to show how natural history specimens could inform and create imagery and art. Our examples ranged from Blaschka glass models, to X-rays, to art created live at the exhibit by the talented Nichola Hope (check out more of her work on instagram @thedrawingeye).

On display we had a selection of taxidermy specimens of UK native species as well as a study skin of a Manx sheerwater (Puffinus puffinus) in all its monochrome glory. Throughout the event both children and adults came up and asked a lot of questions about the objects, and I noticed some reoccurring queries. I have attempted to answer these to the best of my ability below, so that if anyone else reading this faces these same conundrums when wandering their local museum, then hopefully this article will set their mind at ease:

Q: Did you kill them?

A: No, I didn’t! Most the animals you are seeing on display in museums are old specimens, often from the Victorian era when taxidermy was at the height of popularity. Historically, the implications of intense hunting sprees were not fully understood, and the fashion of the time encouraged large collections of specimens. The death of the animal will have been dependent on the hunting or trapping method implemented, those that least damaged the skin of the animal will have been favoured to aid in creating a presentable specimen. The conservation of these old taxidermy specimens in museums means they can be used educationally for generations to come and limits a need for new specimens. Nowadays, new taxidermy or study skins within museums are often the result of an animal kept in captivity, such as in a zoo, dying naturally or being euthanized due to illness, or a wild animal dying accidentally, such as a bird flying into a building.

Q: Is it ‘ethical’?

A: ‘Ethical’ is a subjective term, therefore what is considered ethical varies between taxidermists. Whether the preservation of animal remains, without the inherently unobtainable consent of the animal, is in itself ethical is up to each individual to decide. ‘Ethical-taxidermy’ has become a more frequently used term generally referring to the animal not being killed specifically for the purpose of becoming a mount. However, this refers to a wide range of sources and can range from accidental deaths such as finding an animal dead or road kill, right through to by-products of culling, pet food supply animals and pest control salvages. So the term can be misleading in its lack of distinct definition. A level of transparency and open communication as to the source of the skin should be sought in order to obtain any real clarity on whether a specimen is in line with your personal code of ethics. However, especially when it comes to old mounts, sometimes the exact origin of the animal has been lost to time.

Q: What is the difference between taxidermy and study skins?

A: Since the sixteenth century, taxidermy has aimed to mimic life. The word itself is derived from the Greek ‘taxis’ meaning fixing or arrangement and ‘derma’ meaning skin. The skin of the dead animal is removed and treated before being stuffed and arranged into a lifelike pose. A lot of modern day specimens use pre-made moulds constructed from high-density urethane foam. However some use clay, foam, or a combination of these along with the original skeleton. For smaller specimens wood wool is commonly used.

Historically, there have been a range of stuffing types; when taxidermy was in its infancy, field collectors, hobbyists and early taxidermists often used whatever was to hand. For many years after the dodo’s extinction there were misconceptions about the bird’s appearance because the specimens available had be stuffed with rags and sawdust, which disfigured the skin. In the Victorian era new methods of stuffing were trialled, some less successfully than others. Dr Beevor of Newark-on-Trent trialled a method of covering animal carcasses in a tropical tree sap and placing the skin on top. The technique produced a rough uneven specimen, and so rightly never caught on.

As new technology and techniques have been developed, new types of taxidermy such as freeze-dried mounts and re-creation mounts have been developed. In freeze drying the internal organs are removed but the skeleton and musculature are kept inside the skin and the animal is posed before being placed in a freeze dryer and desiccated. Re-creation mounts requires a great deal of artistry. This is where the fur, feather and skin of other animals is used to create a representation of a different species, e.g. a fisher cat’s skin is used and edited to appear like a red panda.

In taxidermy the aim is to create a specimen that is a lifelike representation of a live animal, whereas the aim with study skins is to preserve the skin and in turn the data we can obtain from it. Study skins are present in all scientific natural history collections and are used for research by visiting scientists to collect a wealth of data. They preserve the morphology (the external characteristics), the DNA and even the isotopes (variants of chemicals) present in particular structures of the animal. Isotope analysis is a relatively new procedure that can offer new information on the diet, migration, ecological niche, as well as the hormone or stress levels of the individual just from sampling a study skin. Even the parts that are removed during the skins preparation can be used to obtain insights when measured, independently examined and analysed at a later date e.g. organ tissue samples can be frozen for further analysis. Isotope analysis has been recently used to find out lifetime patterns in whales, such as pregnancies and stress levels, by analysing the different bands of growth in baleen and earwax removed from whale carcasses.

One specimen is not representative of an entire population, so specimens are collected slowly over time to create a collection containing multiple individuals of one species. Study skins tend to be prepared uniformly so as to be comparable and any differences become apparent. The skins are often stuffed with wood wool or cotton, or a combination of both, wound around a wooden dowel. This uniform preparation is especially important as study skins play a key role in defining species and the determining taxonomy. Taxonomy is the branch of science that defines and classifies groups of biological organisms on the basis of shared characteristics. For each taxon, there are type specimens on which the description and name of a new species is based. These are found by comparing the characteristics and DNA of specimens, and museums worldwide have type specimens in their collections.

For a great example of how study skins can give us new insights, check out this article by the BBC summarising a study by Shane DuBay and Carl Fuldner (published in 2017) on how bird feathers can indicate rises and falls in pollution through history. Or why not read the whole paper here?!

Q: Can I touch them?

A: It is often advised that the public do not touch taxidermy specimens for two reasons: 1) the specimens may have been preserved with toxic chemicals 2) physical handling of the specimens can cause them damage. In any case I would never advise touching a specimen unless a conservator has told you explicitly that it’s okay to.

Toxic chemicals have been used to preserve taxidermy and ward off pests throughout history, the most infamous of which is arsenic. Some of these chemicals can be absorbed through the skin and can cause irritation to eyes and the respiratory system with a danger of cumulative effects. The trace amounts of chemical you will be exposed to through minimal, sporadic, handling of taxidermy are unlikely to cause any health issue. However, it is not known with an individual specimen you stroke the exact amount of chemical you would be exposed to and how that chemical accumulates should you decide, on a whim, to touch everything in a gallery. So, the risk of a one-off handling is small, but still present, and therefore is not advised. Modern taxidermy, post the 1986 Control of Pesticides Regulations (COPR) no longer uses quite such hazardous chemicals and is more likely to be safe to handle. The best approach is to always ask first and follow the directions on any signs rather than to get into the habit of handling specimens.

Handling collections are taxidermy collections, that are deemed safe to handle due to the lack of chemicals present on their surface. Their value lies more in the educational experience of touching them than inherently within the specimen.

Modern study skins are able to be touched as chemical preservation methods are no longer used. With the development of new methods of obtaining data from study skins, such as DNA analysis, chemical preservation methods were phased out due to their disruption of the data these methods aim to obtain. However, some study skins are too delicate for handling, these are usually mounted with a small dowel protruding via which they can be picked up and moved around. Some museum staff comically refer to these as ‘birdsicles’.

Other than the obvious risk of something being dropped, or handled with a little too much vigour; the oil and residues from our hands along with the friction of being lovingly stroked can also damage a specimen over time. A key example of this is Bertie the Bison from the Evolution of Wales gallery at NMW drastically balding over time due to visitors being so enamoured by him as to keep on petting him despite the ‘no touching’ sign.

Q: Are the eyes real?

A: In both taxidermy and study skins the eyes are removed as otherwise they would decompose on the specimen. In taxidermy they are replaced with glass or acrylic eyes. In study skins replacement of the eyes is unnecessary and may pollute the data we can obtain from the skin. Which is why, often in study skins you can see just the stuffing of the interior between the eyelids.

Q: Aren’t they smelly/dirty/dusty?

A: Old taxidermy has a distinct smell that comes from the chemicals applied to the skins. Study skins, where no chemicals are used, can maintain natural scents of the fur, feathers or animals environment. For example, seabird study skins may occasionally still smell salty.

Taxidermy can accumulate dust over time, especially if the conditions it is stored in are not ideal. Museum storerooms are kept clean and any specimens with accumulated dirt or dust are cleaned by conservators, as dust and dirt attracts unwanted pests, and to maintain the specimen’s appearance.

Q: Do videos or seeing the animal in the wild not defeat the purpose of taxidermy?

A: Not everybody has the chance to see animals in the wild, especially not up close, and especially not some of the historical specimens we have of species only found in other counties or that are now extinct. You have to admit, it’s much easier to see a whale, a hyena or even just the particularly small and speedy kingfisher in a museum, than it is to see them in the wild. Plus the sheer scale of Dippy the diplodocus is far easier to grasp (not literally, please refer to the ‘can I touch them’ question!) when you are stood staring up her.

Taxidermy does have it’s limitations, you are only going to see that animal in one pose, and one mount is not representative of all individuals of that species in size or colouring. But the artistry of dioramas often aims to be informative, showing a particular behaviour or feature of that animal, submerging you in a moment in time in that setting, with that animal, and your imagination. Additionally, animals are often displayed in their habits alongside each other; meaning that in one scene you can encounter all a woodland has to offer in a singular gathering.

We must also remember that viewing animals in a museum does not negate the experience of seeing them in wild. It has been used to highlight the plight of species in the wild and through this has contributed to wildlife conservation. In the 1880’s William Hornaday, chief taxidermist of the Smithsonian at the time, took specimens of American bison to Washington to advocate for ceasing their widespread slaughter and leading to the protection of the bison range in Yellowstone.

Personally, from my own experience and talking to others throughout my time volunteering at museums, I have found seeing a taxidermy specimen of a species up close in a museum to be useful in helping me to identify them in their natural habitat through highlighting identifying features and offering immediate comparison to similar species. I feel it has the ability to encourage us to go out and keep looking!

On that note, I leave you here, maybe with fewer questions (quite possibly with more if this has peaked your interest) but hopefully overall a little more at ease with taxidermy.

References

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales. 2017. Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales. [online] Available at: <https://museumwales.tumblr.com/post/156034346012/heres-a-modern-picture-of-bertie-the-bison-from> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

DuBay, S.G. and Fuldner, C.C., 2017. Bird specimens track 135 years of atmospheric black carbon and environmental policy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(43), pp.11321-11326.

Duncan, O., 2018. Not Just A Pretty Face: Why Museums Need Study Skins. [online] Sbnature.org. Available at: <https://www.sbnature.org/publications/blog/2/posts/59/not-just-a-pretty-face-why-museums-need-study-skins> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

Eisenmann, P., Fry, B., Holyoake, C., Coughran, D., Nicol, S. and Nash, S.B., 2016. Isotopic evidence of a wide spectrum of feeding strategies in Southern Hemisphere humpback whale baleen records. PLoS One, 11(5).

Hunt, K.E., Stimmelmayr, R., George, C., Hanns, C., Suydam, R., Brower, H. and Rolland, R.M., 2014. Baleen hormones: a novel tool for retrospective assessment of stress and reproduction in bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus). Conservation physiology, 2(1).

Hunt, K.E., Lysiak, N.S., Moore, M.J. and Rolland, R.M., 2016. Longitudinal progesterone profiles in baleen from female North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) match known calving history. Conservation physiology, 4(1).

Hunt, K.E., Lysiak, N.S., Moore, M. and Rolland, R.M., 2017. Multi-year longitudinal profiles of cortisol and corticosterone recovered from baleen of North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis). General and comparative endocrinology, 254, pp.50-59.

John, K., 2016. What Are Study Skins?. [online] Birdsoutsidemywindow.org. Available at: <https://www.birdsoutsidemywindow.org/2016/12/06/what-are-study-skins/> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

Kelly, K., 2016. ‘Rogue Taxidermy’: A Misunderstood Ethical Art Form Or The Next Hipster Fad?. [online] the Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/nov/16/taxidermy-hipster-art-ethics-morbid-anatomy-museum> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

Kwapis, M., 2015. “ETHICAL” TAXIDERMY – A (REALLY LONG) DISCUSSION — Mickey Alice Kwapis. [online] Mickey Alice Kwapis. Available at: <https://mickeyalicekwapis.com/blog/ethicaltaxidermy> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

Leckert, O., 2018. Inside The Eccentric World Of Ethical Taxidermy Art. [online] Artsy. Available at: <https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-inside-eccentric-ethical-taxidermy-art> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

Metcalfe, J. C. (1981). Taxidermy a complete manual. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd.

Maiorano, H., 2017. The Victorian Naturalist And Their Interest In Taxidermy. [online] Molly Brown House Museum. Available at: <https://mollybrown.org/victorian-naturalist-interest-taxidermy/> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

Marte, F., Péquignot, A. and Von Endt, D.W., 2006. Arsenic in taxidermy collections: history, detection, and management. In Collection Forum.

McShea, P., 2016. Study Skins – What’s Up With The Dead Birds?. [online] Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Available at: <https://carnegiemnh.org/tag/study-skins/> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

Museum of Idaho. 2017. A Brief, Gross History Of Taxidermy. [online] Available at: <https://museumofidaho.org/idaho-ology/a-brief-gross-history-of-taxidermy/> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

National Park Service, 2000. Conserve O Gram: Arsenic Health and Safety. [online] Available at: https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/02-03.pdf [Accessed 7 Jan. 2020].

Newby, K., 2018. Can You Be A Vegan Taxidermist?. [online] Taxidermyco.uk. Available at: <https://taxidermyco.uk/can-vegan-taxidermist/> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

Norman, S.A., Usenko, S. and Trumble, S.J., Lend Me Your (Whale) Ears: Or Why You Should Bother Collecting a Whale’s Earwax.

Pool, M., Odegaard, N. and Huber, M.J., 2005. Identifying the pesticides: Pesticide names, classification, and history of use. Old Poisons, New Problems, a Museum Resource for Managing Contaminated Cultural Materials, 99, pp.5-31.

Ryan, C., McHugh, B., Trueman, C.N., Sabin, R., Deaville, R., Harrod, C., Berrow, S.D. and Ian, O., 2013. Stable isotope analysis of baleen reveals resource partitioning among sympatric rorquals and population structure in fin whales. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 479, pp.251-261.

Strekopytov, S., Brownscombe, W., Lapinee, C., Sykes, D., Spratt, J., Jeffries, T.E. and Jones, C.G., 2017. Arsenic and mercury in bird feathers: Identification and quantification of inorganic pesticide residues in natural history collections using multiple analytical and imaging techniques. Microchemical journal, 130, pp.301-309.

The Brain Scoop supported by The Field Museum in Chicago, IL, 2014. Year Of The Passenger Pigeon. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPRpX25L5DU> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

Webster, M., 2017. The Extended Specimen. 1st ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Would, A., 2018. The Curious Creatures Of Victorian Taxidermy | History Today. [online] Historytoday.com. Available at: <https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/curious-creatures-victorian-taxidermy> [Accessed 10 March 2020].

- March 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (6)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (8)

- March 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (3)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (4)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (5)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (2)

- March 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- August 2018 (2)

- July 2018 (5)

- June 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (3)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (3)

- May 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (4)