Reconstructing the Past: The working relationship between archaeology and conservation at Cardiff University in the case of a Harpstedter Rauftoph vessel from Piepenkopf Hillfort

14 March 2023Archaeology and conservation are intrinsically linked. Indeed, some may argue that archaeological conservation is just an extension of post-excavation. This would an over simplification – conservation is much more than cleaning and sticking things together with superglue. Despite conservators often training within the museum environment, the opposite is not true either. Is conservation the bridge between heritage and history? To understand the relationship today, we turn to the past.

A Brief History of Archaeological Conservation

Conservation as a discipline only began to emerge in the 19th century. At this time, care of antiquities was beginning to formalise, in part due to the changes in archaeological investigation. With increased certification, documentation, and communication, both fields evolved into semi-recognisable disciplines. Standard procedures are devised, primarily with aesthetics at heart.

1922 can be regarded as a key year in the development of the archaeology-conservation relationship. On November 4th, Howard Carter famously discovered the previously unknown tomb of Tutankhamun. The story of this is fairly well known, especially with the centenary just passing, but the role of Alfred Lucas is relatively unknown. Lucas, a chemist, and his assistant Arthur Mace, a young archaeologist, worked in a makeshift on-site lab studying and caring for artefacts in a very modern manner. Lucas emphasised the importance of understanding materials, manufacture, and decay in developing treatments. He was aware of the limitations of the newly used cellulose nitrate and was extremely diligent in his documentation, which can still be found at the Griffith Institute in Oxford. In 1924, he published on the first English language conservation books: Antiquities: Their Preservation and Restoration. Lucas and Mace were pioneers.

Lucas and Mace working on one of Tutankhamun’s chariots outside of his tomb. Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

As decades passed, a realisation was made that treatments and interpretation could be improved by forming a stronger dialogue between the two disciplines. By sharing knowledge of archaeological science, manufacture, and craftsmanship, interpretation of finds and integration into the present could be improved. This can be seen in the wide consultation with craftsmen by archaeologists prior to the treatment of the Danish bog bodies Tollund and Grauballe Men in 1950 and 1952.

Nowadays, greater consideration is made about stability, sustainability, and interpretation and less emphasis placed on aesthetics. Through the continuing relationship, we collectively have came to understand that sometimes decay processes and corrosion products are essential in understanding a site’s profile – conservation has changed its approach to better address the needs of archaeologists. Unfortunately, this information often makes its way to archaeologists after the phase of written interpretation has passed. Conversely, archaeology benefits from the close ties conservation has with museum practice, especially in the concept of decolonialisation, as well as providing conservation with specific treatment goals.

Piepenkopf Hillfort Excavation

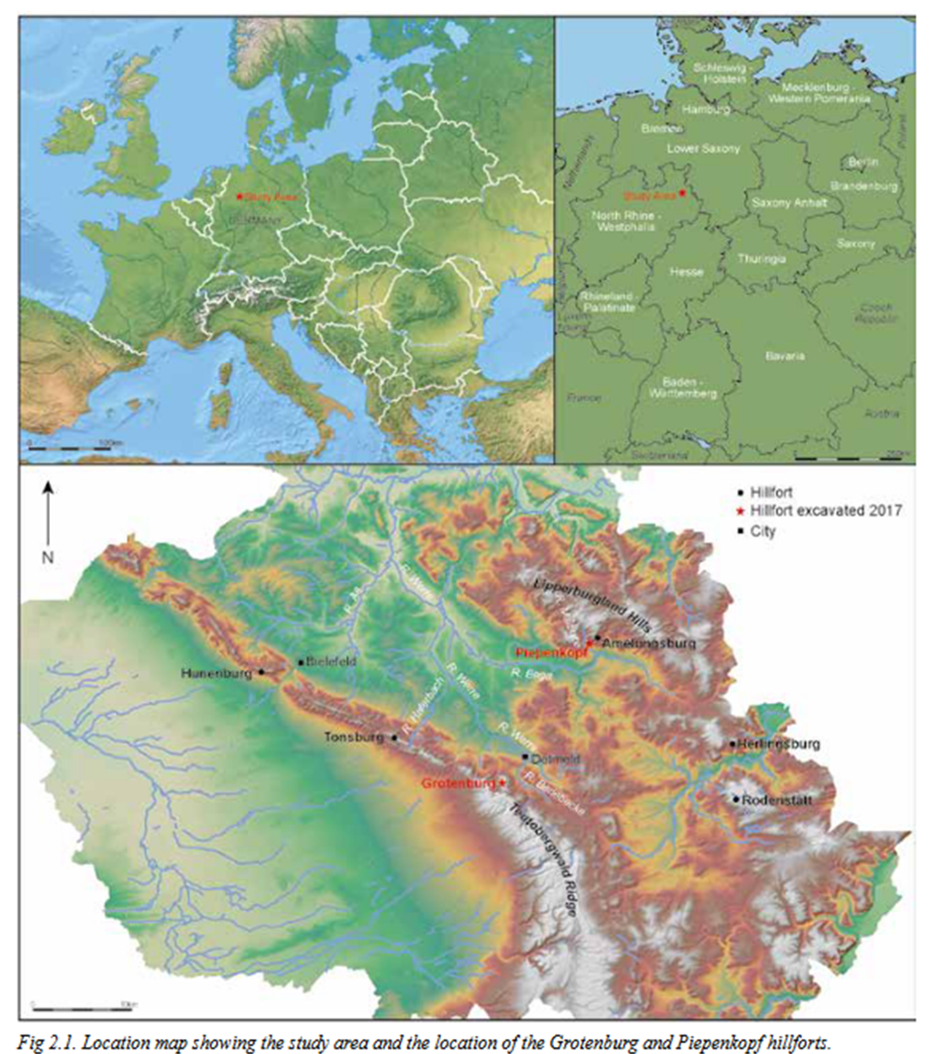

In 2017, Cardiff University began excavating the Piepenkopf Iron Age hillfort, Westphalia Germany, in conjunction with Lippesches Landesmuseum Detmold (LLM) and Bochum University. The aim was to explore a little understood site and gather different approaches to excavation together. The hillfort has previously been excavated in 1822 and 1939, with radio carbon dating suggesting a date of 266 BC (±65 years). Westphalia is a region defined by either an abundance or absence of hillforts – the frontier of the Germanic and Celtic worlds – and Piepenkopf sits along this demarcation.

Map of Europe, Germany, and Westphalia showing the location of Piepenkopf (Davis et al, 2018)

The soil is a buff to orange sandy clay predominantly with much quartzite inclusions and is fairly acidic as a result of the site’s association with pine forests. As a result, the main find type is pottery with the most significant find in the inaugural season being 111 sherds of pottery from trench 2. And then in 2019, something even more significant was found.

Piepenkopf Pot in situ during excavation in 2019. Courtesy of Mark Lodwick

In trench 2EE, in what appeared to be a stone lined pit, an apparent whole but smashed vessel emerged. From the way is had been deposited, it was thought to have been deliberately smashed. After careful excavation and some on site attempts at reconstruction during post-ex, the deposit revealed itself to be approximately 165 sherds of a large rough ware vessel.

Piepenkopf pot prior to treatment by myself but after cleaning by Amy Meeson. The rim sherds are in the left hand quarter and the base middle top. The right top quarter show the interior in contrast to the rest displaying exterior. Author’s own.

The Harpstedter Rauftoph Vessel

In addition to the base, archaeologists believed the entire rim and body of the vessel to be present and the diameter of the rim to be nearly 40cm. The texture of the pot and finger impressed rim showed that this was a rare Harpstedter Rauftoph pot. These vessels date from the 5th to the 1st century BC usually and within a small region of Westphalia. They have been conflated with the La Tene in the literature, despite being hundreds of miles away from the frontier of that culture! PhD student Grace Hewitt’s thesis, completed last year, attempts to revolutionise the categorisation of Germanic Iron Age pottery, and this vessel featured heavily.

As large, coarse, prehistoric earthenware vessels, Harpstedter vessels were hand built in two pieces with the base constructed first. This was left to dry until leather hard, after which the walls were built up to the desired height. Finally, the rim was decorated with regularly spaced finger impressions before being fired at a relatively low temperature. At some point, the a slip would have been applied to give it its characteristic rough surface but this method of application remains a mystery. Experimental archaeologists are investigating, and it hoped this vessel will aid them. Even more exciting, residues were present on the interior of the vessel, raising the possibility of lipid testing to determine the use of the pot. This was especially important as the use of this type of vessel is not yet understood. Others have been found to contain human remains whereas others are thought to be feasting vessels. In fact, if all sherds of the Harpstedter type were constructed into whole vessels, they would total only 5. Piepenkopf would be the sixth.

There were big expectations for this pot. In addition to aiding with Hewitt’s thesis, Ian Dennis planned to draw the pot to illustrate. Archaeological illustration shows the profile, size, and completeness of a vessel and so a balance was required between potential for investigation, stability, and aesthetic considerations for display.

Conservation Considerations

Adhesive

The fabric of the vessel, as a low fired ceramic, was porous and weak, meaning that the edges required consolidating before the pot could be reconstructed. This was the work conducted by Amy Meeson and she chose to use 5% Paraloid B72 in acetone and industrial methylated spirits. My adhesive had to be thicker and stronger whilst still being workable at high viscosities. More importantly, it had to be reversible. Piepenkopf hillfort is still a working site and there was the possibility that more of the vessel would be recovered. If that were to occur, there had to be the opportunity to incorporate these sherds into the pot, which may require pieces being removed first. I also chose to use Paraloid B72 but at 30% as it was strong and viscous enough to provide the strength needed. My solvent choice was acetone with 10% ethanol to reduce the stringiness of Paraloid when used at high percentages. Paraloid B72 is up to 100% reversible up to 100 years after application.

Process of reconstructing the Piepenkopf Pot which was built up from the base and down from the rim simultaneously. Due to the flare from the base, it was more stable to construct inverted. Author’s own.

Fills

Once the pot was returned to its standard orientation, it was apparent that this was not a complete vessel. Plaster fills had already been inserted to support the vessel during construction and now it was apparent that further would be required for long term stability and transport to Germany by car. The question was, how many? Clearly they were needed but too many would have decreased the investigative value of the vessel. After consulting with Ian Dennis, it was decided that some holes would remain but only where no sherds were isolated and thus at risk of becoming detached in transportation. Fills were made of dental plaster in a 2:1 ratio with sand to increase strength and be a better match to the texture of the interior of the vessel. A small experiment was conducted into the perfect ratio of plaster to sand for this aim. Smaller cracks along poor joins were filled with Paraloid B72 and microballoons, tinted with dry pigment.

Results of experiment in to plaster-sand ration prior to testing by scraping with a dental tool and attempting to snap the pieces by hand. Increasing sand proportion left to right from 1:4 to 4:1. Author’s own.

Fills were constructed into two layers. The first was recessed from the surface and provided support. The second was applied with a sponge to imitate the texture of the rough slip. Both were tinted with dry pigment to match tonally but unfortunately it was not even – one fill turned pink when the Indian red pigment mixed more evenly than in previous batches and one turned blue after shaping. They required painting.

Acrylic paint was the material of choice due to its stability. Again, consultation with Ian Dennis was conducted to determine the overall appearance – should the fills stand out, blend tonally, or match closely? We agreed that, because this vessel was to be displayed and to highlight the near completeness, that a close match was desired. Thin layers of watered-down acrylic were applied until this was achieved.

Inpainting of fills during treatment and in final photos. Author’s own.

Now what for the pot?

With the help of Mark Lodwick, the pot has been photographed for publication and for illustration. It has also been 3D scanned, becoming the largest object scanned by the Artex Spider to date and required the cannibalisation of desk chair to create a large enough spinning platform. Illustration is still yet to occur (as of March 2023) and neither has lipid testing (as of March 2023), though samples have been selected (14/03/2023). Dissemination about the pot has been an ongoing process by myself and the School of History, Archaeology, and Religion, with another report on the site due soon. For now, the pot is packaged in a bespoke box in preparation for its return trip to Germany beginning March 17th 2023. Please Ian, drive carefully.

Completed reconstruction of Piepenkopf Pot showing size (scale is 20cm), extent of fills, and colour matching. Courtesy: Mark Lodwick.

This blog has been adapted from a presentation given by the author during the SHARESeminar Conservation Considerations, March 13th, 2023.

- March 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (6)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (8)

- March 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (3)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (4)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (5)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (2)

- March 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- August 2018 (2)

- July 2018 (5)

- June 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (3)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (3)

- May 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (4)