Wales in the Digital Economy: Emerging Evidence on the Importance of Place

14 February 2019

In our latest post, Professor Calvin Jones outlines some of the findings from the Digital Maturity Survey 2018.

Most of us now know that technological progress will bring significant changes in the ways economies are organized, and that these changes will create ‘winners and losers’ across different occupations, industries and individual firms.

However, whilst analysis has been extensive, not much has focused on how different places, and different types of places will be affected and how far they will be able to respond.

What spatial discussion there is has focused on the ‘urban-rural divide’, with the latter expected to be in a worse position to take advantage of opportunities – in part related to the (part perceived, part real) lack of hard infrastructure in rural areas, including high-speed fixed and mobile internet connections. The position is however not so straightforward.

For one thing, a number of occupations likely to be centrally affected by AI and automation are largely urban based – low and medium skilled white-collar work – whilst rural areas typically have more firms per capita, and perhaps then a more ‘nimble’ economic landscape.

Added to this, previous commentators have suggested that Wales in particular may be badly placed to take advantage of emerging technology.

Superfast Cymru Business Exploitation

Our study of businesses across Wales, reporting on their take-up and use of superfast broadband, is beginning to shed some light on the answers to questions around ‘tech’ readiness, at least for SMEs and smaller social enterprises.

Here, in partnership with Welsh Government and the EU we are trying to map what tech-related behaviours exist, or are emerging within Welsh SMEs, with a view to understanding the impacts on their competitiveness. Whilst we would like (as always) more data, we can begin to report some results.

To cut to the chase our data suggest that there is a significant difference in the levels of digital take-up between Welsh SMEs in urban and rural areas, with the latter lagging behind. This difference persists between our 2017 and 2018 survey. With over 400 responses in each year (albeit with some firms responding in both) we can be 99% sure these differences are real, and not a statistical quirk.

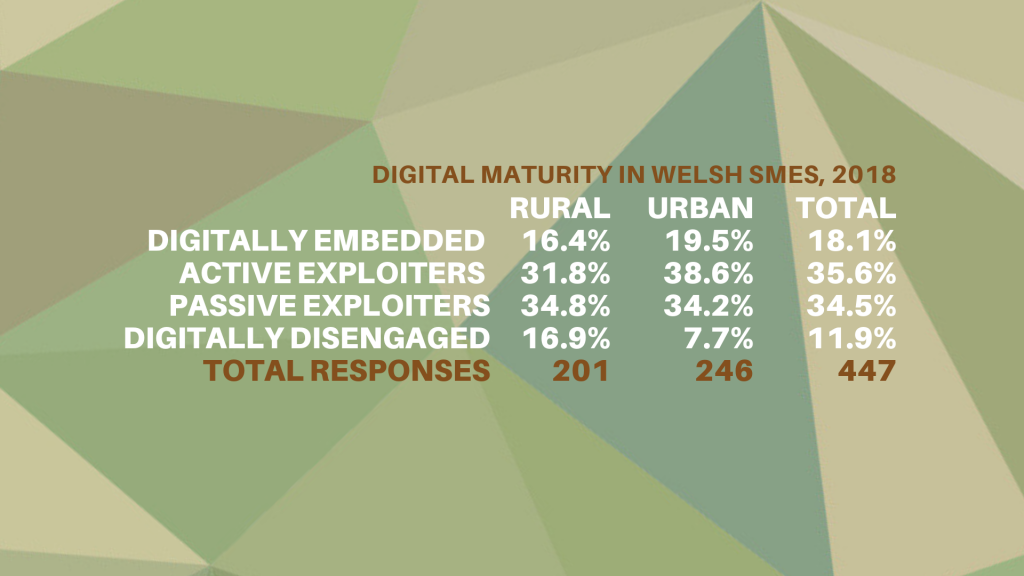

We base our analysis on a Digital Maturity Index, which bundles a number of factors including broadband access, use of cloud services and IT competencies into a single indicative number that represents the behaviour and readiness of firms.

Some Emerging Urban-Rural Findings

The average score for rural firms in 2018 at 44.1 was over three points lower than for urban firms (47.5). Whilst this might not sound much, further analysis on behaviours that ‘clusters’ firms into types shows some stark implications.

At the top end, there is some difference, with 19.5% of our urban sample reaching the highest level of ‘Digitally Embedded’ compared to 16.4% of rural businesses. However, at the ‘bottom end’ we characterize almost 17% of rural firms as ‘Digitally Disengaged’, compare to less than half this proportion of urban firms.

Caution should be exercised over these detailed classifications with only 200 or so firms in each column here, but the persistence of these results since 2017 is notable.

Our next task is to understand why these differences occur.

Is it perhaps the sector, size, age or management of our rural sample that is different or is it something about the nature of rurality itself – including more limited access to markets or connectivity infrastructure – that is driving these findings?

We will also be publishing our findings on the current and future opportunities for areas to benefit from digital technologies in the coming weeks.

And Within Urban Places?

Whilst the vast majority of the ‘broadband and space’ debate has been about the urban-rural divide, some papers have suggested that urban places are not the same – and particularly that post-industrial urban areas sited next to ‘tech leader’ hubs do not benefit from technology as much.

We have tried to test this hypothesis with our survey data, splitting Wales’ largest city-region into its five (post industrial and poor) ‘Valleys’ authorities, and its five ‘Coastal’ (and relatively more prosperous) authorities. Here the data are more limited – with only around 50 responses from firms within the Valleys in each year we are unable to say much about ‘real’ differences with any certainty. As we amalgamate the data for different years, this will change (expecting of course almost all firms to move up the digital ladder over time).

In the meantime, it is worth noting that the maturity index for our sample of Valleys firms was lower in both 2017 and 2018 than for Coastal firms, albeit by a smaller margin than for the Urban-Rural split, and with only the 2017 difference (just) statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. Again with strong caveats about small sample sizes note that in 2018 double the proportion of Valleys respondents were digitally disengaged (10.9%) compared to the Coast (5.2%).

If these differences are borne out as the data improve, they may reinforce the importance of the different positions of firms in the Valleys and Coast in terms of the factors that are thought to drive digital exploitation.

Secondary ONS data show that firms in the Valleys as a whole are smaller than those on the coast, are less likely to be in industries thought to benefit most from technology (professional services, finance and utilities for example), and face a local workforce with lower levels of training and far lower levels of university qualifications. These characteristics suggest that ‘policy off’, an increased importance of broadband, AI and automation in economic production may lead to even more uneven development across the region.

The findings reported here are not conclusive. We need more survey data, more statistical analysis and more corroboration from our qualitative case study work before we can be sure what is driving digital exploitation – and its commercial outcomes – across space.

However, even this early analysis shows some intriguing differences that suggest policy in Wales needs to take full account of how firms (and by extension people) are responding to the challenges of the digital economy across the full geography of Wales.

Professor Calvin Jones is Deputy Dean for Public Value and External Relations at Cardiff Business School.

This post was prepared in collaboration with WERU researchers, Dr Dylan Henderson, Neil Roche and Chen Xu.

The Digital Maturity Survey 2018 was carried out by the Welsh Economy Research Unit at Cardiff Business School. The School’s research forms part of the Superfast Broadband Business Exploitation project, part-funded by the European Regional Development Fund through the Welsh Government.

Comments

- March 2024

- April 2023

- August 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

1 comment

Comments are closed.