Keir Starmer’s ‘radical federalism’

10 April 2020

The election of Keir Starmer as Labour leader has come during one of the greatest crises that this country has faced. In contrast to the fanfare that usually greets a new leader, Starmer’s election was announced via an email to party members. Nevertheless, Starmer will not worry about such celebrations as he begins his role during a period where effective opposition is vital.

It might seem slightly superfluous to talk about constitutional issues during the coronavirus outbreak, but, if simply to take our minds off it for a brief moment, it is worth considering the future direction of policy under Starmer’s leadership. In particular, what will his leadership mean for Labour’s policies towards Wales, the constitution and devolution?

Starmer’s position during the leadership election was in line with the other leadership candidates, Lisa Nandy and Rebecca Long-Bailey, namely that a serious rethink is required on the British constitution. At a hustings in Cardiff, Starmer insisted that ‘radical federalism’ was needed, “where more powers are closer to the people”.

‘Radical federalism’ is not a new idea. In fact, on this very blog I wrote about then Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell’s proposals for ‘radical federalism’ across the UK. In that post, I argued that if federalism was to be introduced, then important questions needed to be answered about how it would work: how to account for different sized parliaments across the UK, the possibility of a second chamber and how that would work, the role of current Welsh MPs in Parliament and so on. In the period since McDonnell’s pronouncements, a clear policy has still not been delivered by the party.

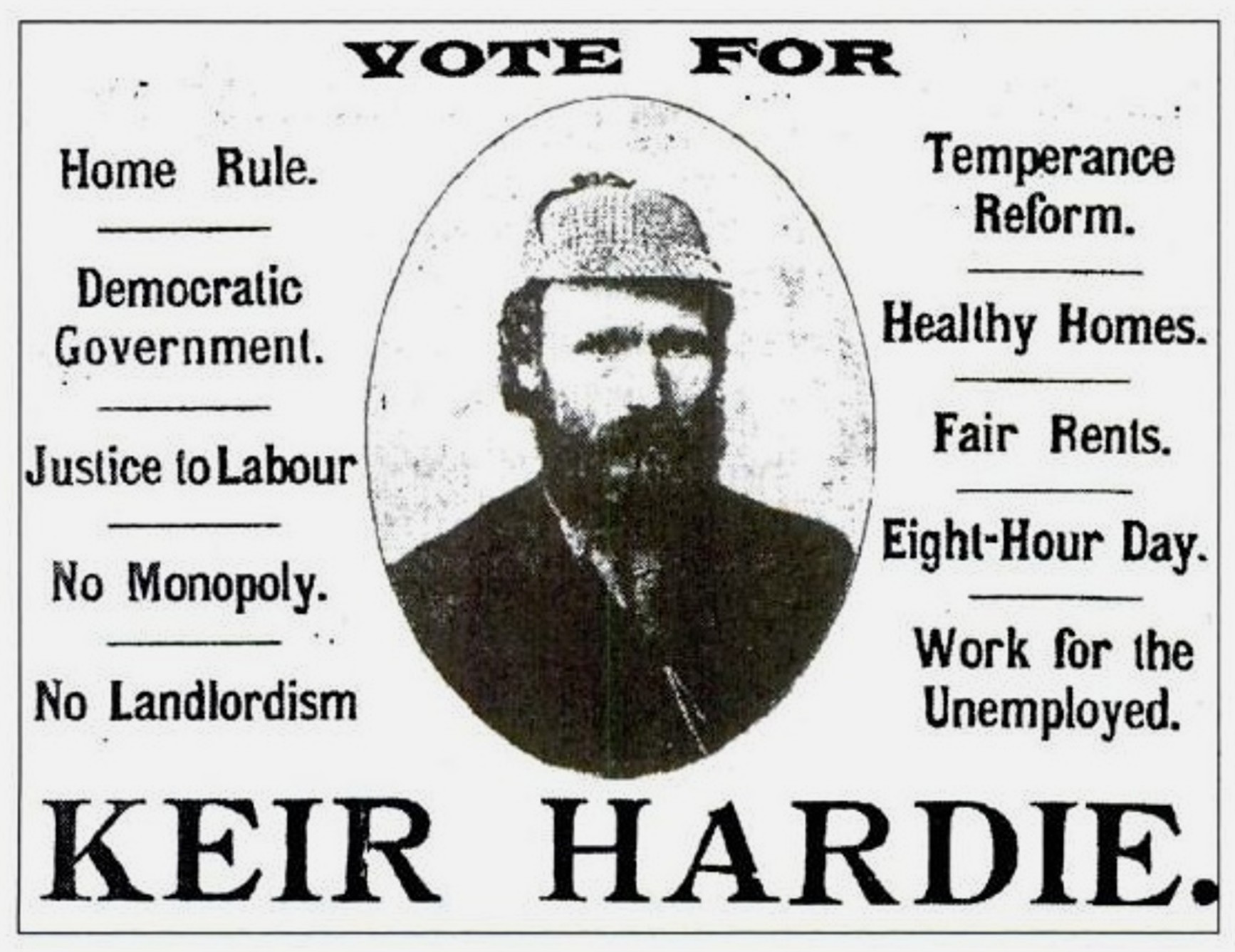

Considering the current crisis, it would be understandable for Starmer to put these constitutional issues on the back burner for a moment. Yet, he has continued to argue the case for a change in the constitution and has recently announced plans for a ‘devolution revolution’ across the UK and the establishment of a constitutional convention. Writing in the Daily Herald, Starmer invoked the spirit of Labour founder Keir Hardie, insisting that Hardie “was not a supporter of nationalism but of home rule for Scotland within the UK”. Following in the footsteps of this tradition, Starmer promised that as leader he would “build a future on the principle of federalism”. He will hope that his intervention might go some way to convince Scottish voters who may not be fully behind independence, but who would like to see increased powers for Scotland, to return to the Labour Party.

At the time of writing, since becoming leader Starmer has yet to write a similar piece on the place of Wales within his plans. However, we can glean some information from an article he wrote for Wales Online during the leadership campaign. In the piece, Starmer wrote of his plans in much the same way as he did in relation to Scotland. He conjured up the spirit of Wales’ radical past, while praising the work done by the Welsh Labour government since devolution. He also wrote of setting up a constitutional convention with the aim of bringing power closer to the people.

In Wales, we do not see the same level of enthusiasm for constitutional issues as we do in Scotland. Yet, the most recent St David’s Day poll results should be taken note of by Starmer and the Labour Party. 43% of people in Wales wanted more powers (including 59% of Labour voters), while 11% wanted independence, indicating a majority of 54% of people who wanted to see some form of constitutional change to Wales, not including the 25% who are happy with the status quo. Although not as vibrant as the debate in Scotland, there does appear to be an appetite for further changes to Wales’ devolution settlement.

For now, precise details on Starmer’s plans are thin. On the convention itself, there remain unanswered question on such issues as the relationship between this constitutional convention and previous conventions mooted by the Labour Party. Will it include the same plans as detailed in Labour’s 2019 manifesto on a constitutional convention, for instance? It is perhaps too early to expect Starmer to release details, especially given the current crisis, but pro-devolution supporters of the Labour Party will be hoping that the leadership gives the issue serious thought.

Starmer will also have to be wary of members of his own party who are lukewarm towards the idea of further devolution. For example, in a parliamentary debate on the Commission on Justice in Wales, Islwyn MP Chris Evans argued: “For me, this is not a constitutional debate. There is a problem right now and action has to be taken. The priority for Wales is not constitutional change or more devolution; it is tackling the problem of the prison population and reoffending rates”. Chris Bryant also questioned the idea of devolving justice to Wales. He said: “My question in relation to the proposal on the table is: does devolution solve any of those problems? I am afraid it does not”. He expressed concern that the UK Government would simply be devolving blame: “If anything, I am terrified that the Government might bite off the right hon. Lady’s hand and say, ‘Yes, devolve it,’ because I know what happens. They devolve the power and the responsibility so that they can devolve the blame when the service is not delivered properly, because they do not devolve the right amount of funding to go with it”.

Another example where there is disagreement within the Welsh Labour Party is on welfare. Former First Minister Carwyn Jones argued that Wales would ‘lose out’ if welfare was devolved, but very quickly into his term as First Minister, Mark Drakeford suggested that the devolution of the administration of welfare ought to be considered. Getting consensus on these issues might prove tricky for the new Labour leader.

The significance of the future relationship between Wales and Westminster has also increased recently given new boundary proposals that could see Wales lose a quarter of its representation at Westminster. As the Electoral Reform Society have warned, this could put serious pressure on an already over-stretched Assembly. This will need to be considered by the Labour Party in developing its proposals.

Of course, the basis of a constitutional convention should not be about devolution for its own sake. Instead, it needs to have at its foundation the goal of improving the lives of people in Wales and throughout the UK. How would transforming the UK’s constitution tackle poverty in Wales, for example? Would it allow a Welsh Parliament to solve Wales’ economic and social problems? How would a federal UK devolve power not just to political institutions but directly to the people? Starmer appears determined to address these issues, but Labour’s policy needs to be based on more than words if it is to offer an inspiring vision for the future of the UK.

- June 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Rugby

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections