Consolidation, Not Conversion: Understanding Wales’s Ongoing Realignment

17 December 2025

This is a joint post by Jac Larner (Cardiff) and James Griffiths (University of Manchester). They received substantive input from Richard Wyn Jones and Ed Gareth Poole (Cardiff), and questionnaire design support from Joseph Phillips (Cardiff) and Ceri Fowler (University of Oxford).

Multilevel electoral systems routinely produce different voting patterns across tiers, but Wales is experiencing something distinct: the emergence of autonomous realignment dynamics that differ from UK-wide trends. While Reform UK’s growth reflects broader British patterns, Plaid Cymru’s consolidation of progressive votes represents a Wales-specific political development. This post examines new survey data evidence for this dual-track realignment, and looks at why people are switching.

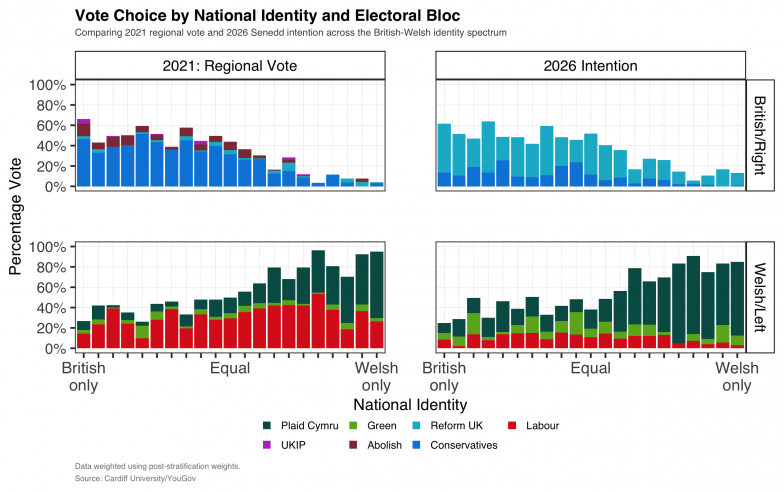

Between 28th November and 10th December we surveyed approximately 2,500 adults in Wales online via YouGov (this is not using YouGov’s MRP weighting method used for ITV polls). Figure 1 illustrates the reported vote intention for next May’s 2026 Senedd election. The headline is largely the same as previous polls: Plaid Cymru and Reform UK polling as Wales’ two largest parties (with slight advantage to Plaid), Labour and the Conservatives have collapsed to around 10% each,* and the Greens up to 9%. For the 2026 Senedd election, conducted under the new electoral system, this would see Plaid Cymru and Reform as comfortably the largest parties but both considerably short of a majority (if you want to play around with seat numbers you can do so here.)

Figure 1: Senedd Vote Intention. Note weights are YouGov’s standard population weights, NOT the MRP weights used in ITV Cymru Wales polls.

Consolidation Within Blocs: The Structure That Persists

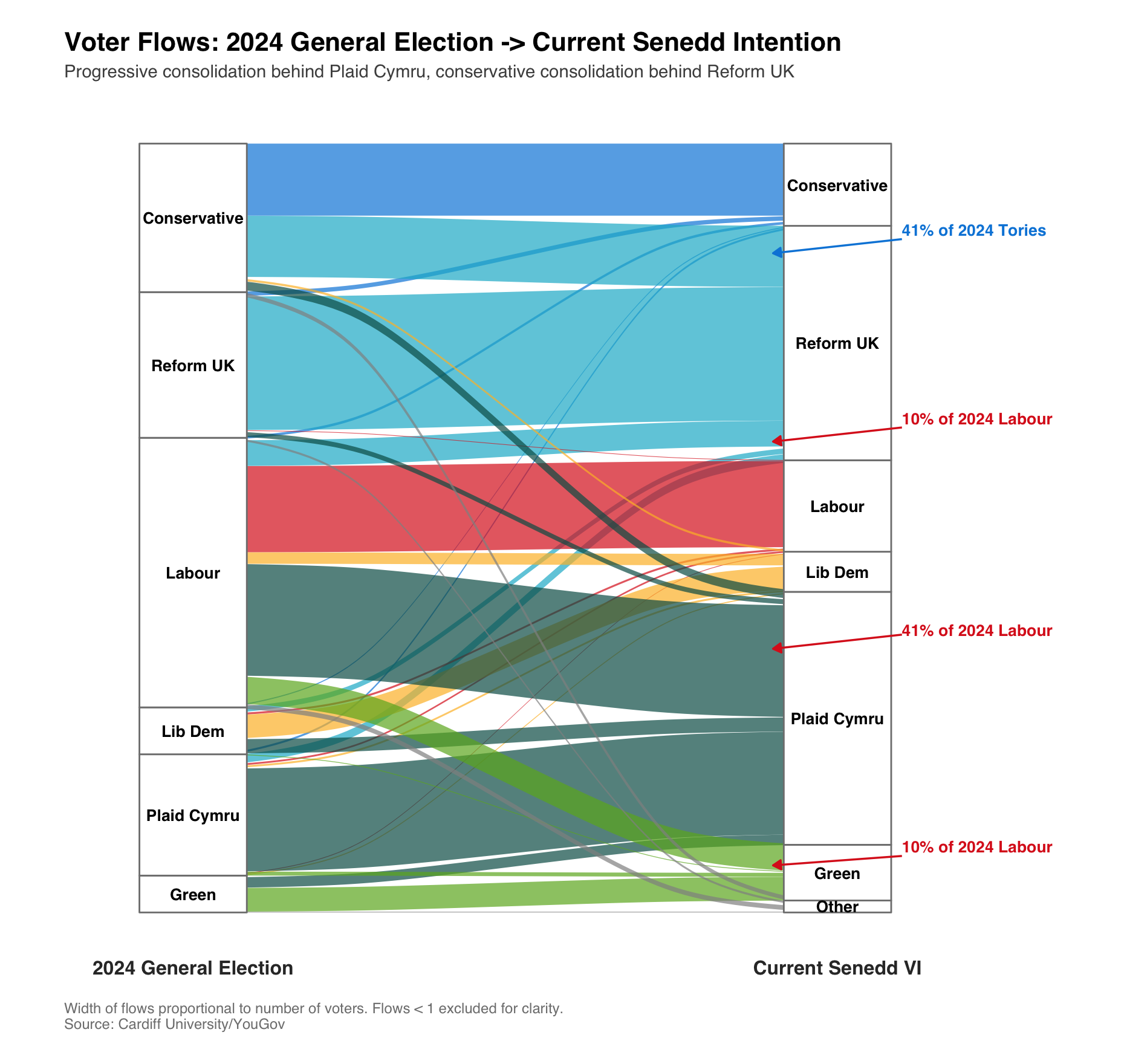

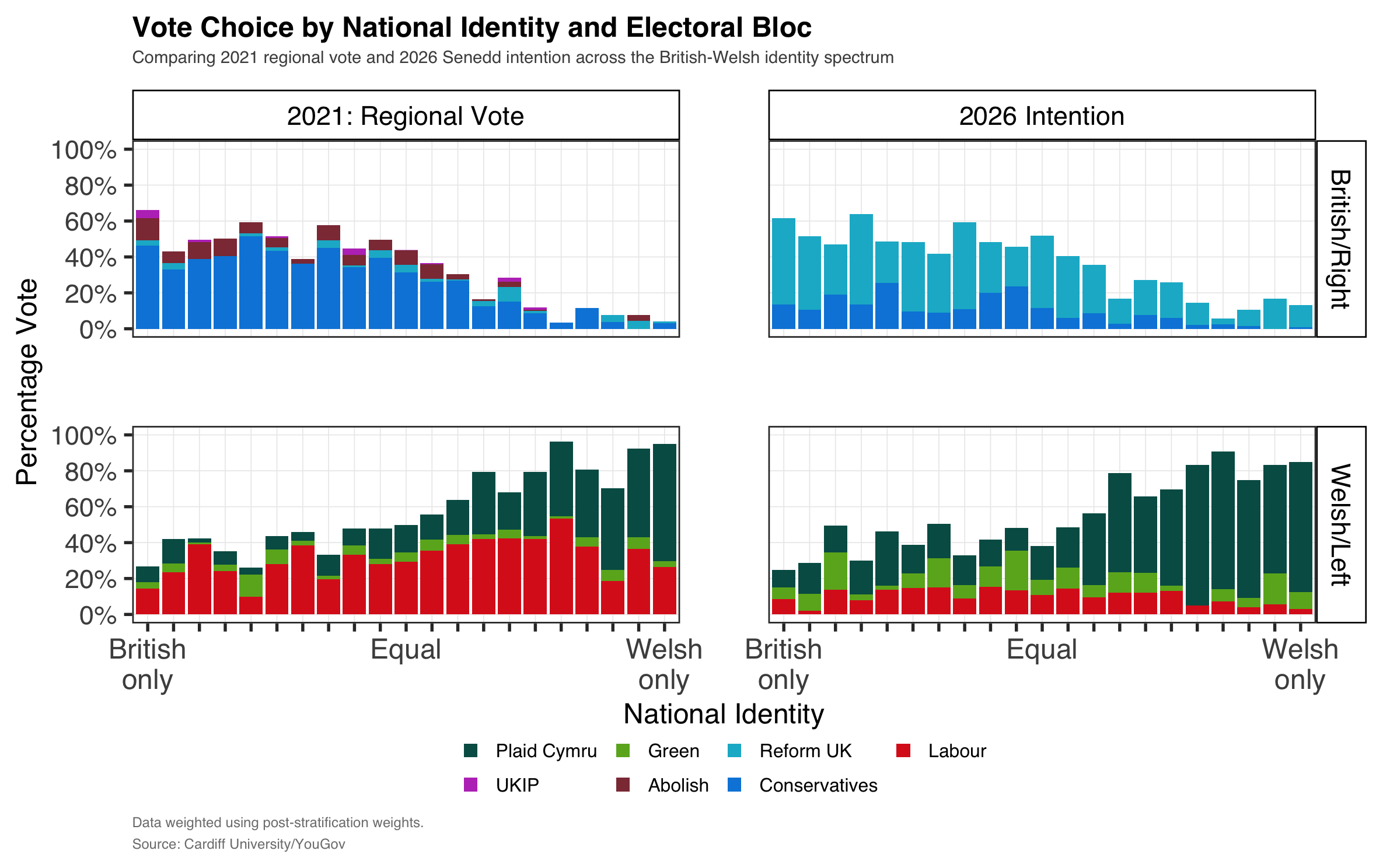

To understand what’s happening requires recognising that Welsh electoral politics has long been organized around two distinct coalitional blocs, structured primarily by national identity. On one side sits a progressive/Welsh-identifying coalition comprising Labour, Plaid Cymru, and, more recently, the Greens. On the other, a conservative/British-identifying coalition of Conservatives and the various iterations of the UK Independence Party (UKIP, Brexit Party, Reform UK) as well as, previously, the Abolish the Welsh Assembly Party.** This structure has proven remarkably resilient, surviving even the 2016 EU referendum, which fundamentally restructured British politics around Brexit attitudes.

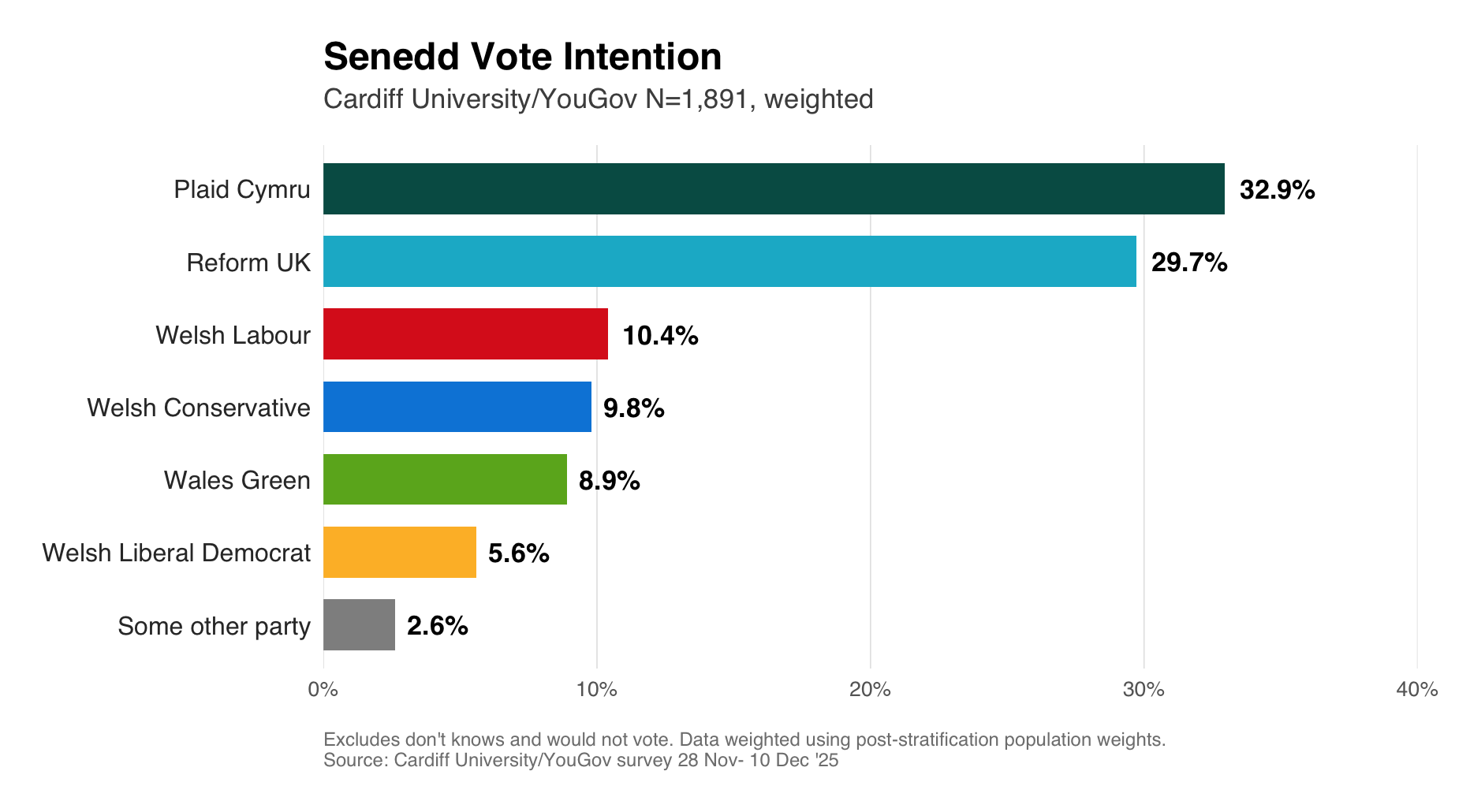

The two dimensions—national identity and Brexit—now substantially overlap. British-identifying voters overwhelmingly support pro-Brexit right-of-centre parties; Welsh-identifying voters cluster around anti-Brexit left-of-centre alternatives. This alignment creates a robust structure: voters aren’t choosing between parties with different Brexit positions within their national identity group. They’re choosing between parties that share both their identity orientation and their Brexit/cultural attitudes. Figure 2 illustrates this clearly below.

Figure 2: Sankey of vote flows

What makes the current moment distinctive is that we’re witnessing consolidation within these blocs rather than mass movement between them. Comparing 2021’s regional list vote with current polling reveals the pattern starkly. In 2021, Labour dominated the Welsh-identifying progressive bloc, winning the majority of these voters. Plaid Cymru held perhaps a quarter to a third of this coalition. Today, those proportions have nearly inverted: Plaid Cymru has absorbed the bulk of Welsh-identifying progressive support, with Labour retaining only a residual share.*** But crucially, the total size of the Welsh-identifying progressive bloc hasn’t dramatically shifted. These voters haven’t abandoned progressive politics or embraced Brexit; they’ve concluded that Plaid Cymru, not Labour, is the better option for them.

Figure 3: Wales’ Electoral Blocs. Note: Wales has a different electoral system for the 2026 election compared to the one used in 2021, so comparisons will be imperfect. We have chosen to compare regional list vote in 2021 with current vote intention, as it is the closest comparator. We have chosen not to report the Liberal Democrats and ‘Other’ due to low levels of support.

The mirror image appears on the British-identifying right. In 2021, the Conservatives commanded this bloc as the previous support for UKIP/Brexit Party largely collapsed. Today, Reform UK has absorbed most Conservative support among British-identifying voters. Again, the bloc itself hasn’t fundamentally changed size or orientation. It remains pro-Brexit, culturally conservative, and sceptical of devolution. What’s changed is which party these voters trust to represent those commitments.

This pattern of within-bloc consolidation has several important implications. First, it clarifies the coalition/cooperation mathematics that will structure post-2026 governance. Despite their long and sometimes bitter history of electoral competition, Plaid Cymru and Labour remain natural coalition partners because they draw from the same underlying voting bloc. Their voters share similar identities, Brexit attitudes, and policy preferences, even if those voters currently prefer Plaid to Labour. A Plaid-Labour coalition or collaboration would represent the Welsh-identifying progressive bloc in the Welsh electorate. Added to this mix the Greens and Liberal Democrats, and there are far more natural combinations within this bloc.

Reform UK and the Conservatives face a different challenge. They too share a voting bloc, but Reform’s growth comes almost entirely at Conservative expense and, critically, current evidence suggests they aren’t winning enough Labour supporters to substantially grow the overall size of this bloc. Every Reform vote is effectively subtracted from the Conservatives, weakening the only party with which Reform could plausibly govern.

Second, within-bloc consolidation suggests different durability than between-bloc realignment. When voters switch parties but remain within their political coalition, they haven’t crossed a fundamental psychological threshold. The barrier to switching back is lower, if circumstances change or the new party disappoints. But they also haven’t betrayed core identity commitments, which makes the switch easier to sustain than ideological conversion. The question becomes whether Plaid Cymru can deliver on the expectations of newly consolidated Welsh-identifying progressives, and whether Reform UK can maintain enthusiasm once protest sentiment fades.

Why Voters Say They’re Switching

To understand motivations beyond stated party preference, respondents who indicated they would vote for Plaid Cymru or Reform UK were asked to select which statement best described their choice.**** The options provided were derived from a mixture of previous open text responses in surveys, and the work being done in Scotland by the Scottish Election Study team. These options are listed below in Table 1.

| Plaid Cymru voters say… | Reform UK voters say… | |

| There’s no real difference between the other parties | There’s no real difference between the other parties | |

| Rhun ap Iorwerth is the only leader who understands ordinary people’s problems | Nigel Farage is the only leader who understands ordinary people’s problems | |

| Devolution is at risk unless pressure is kept up | Brexit is at risk unless pressure is kept up | |

| They’re the only party serious about standing up for Wales | They’re the only party serious about tackling immigration | |

| At least it’s something new – they can’t make a worse mess than anyone else | At least it’s something new – they can’t make a worse mess than anyone else | |

| They’re best placed to stop Reform UK | They’re best placed to stop Plaid Cymru | |

| Some other reason (open text) | Some other reason (open text) | |

| Don’t know | Don’t know |

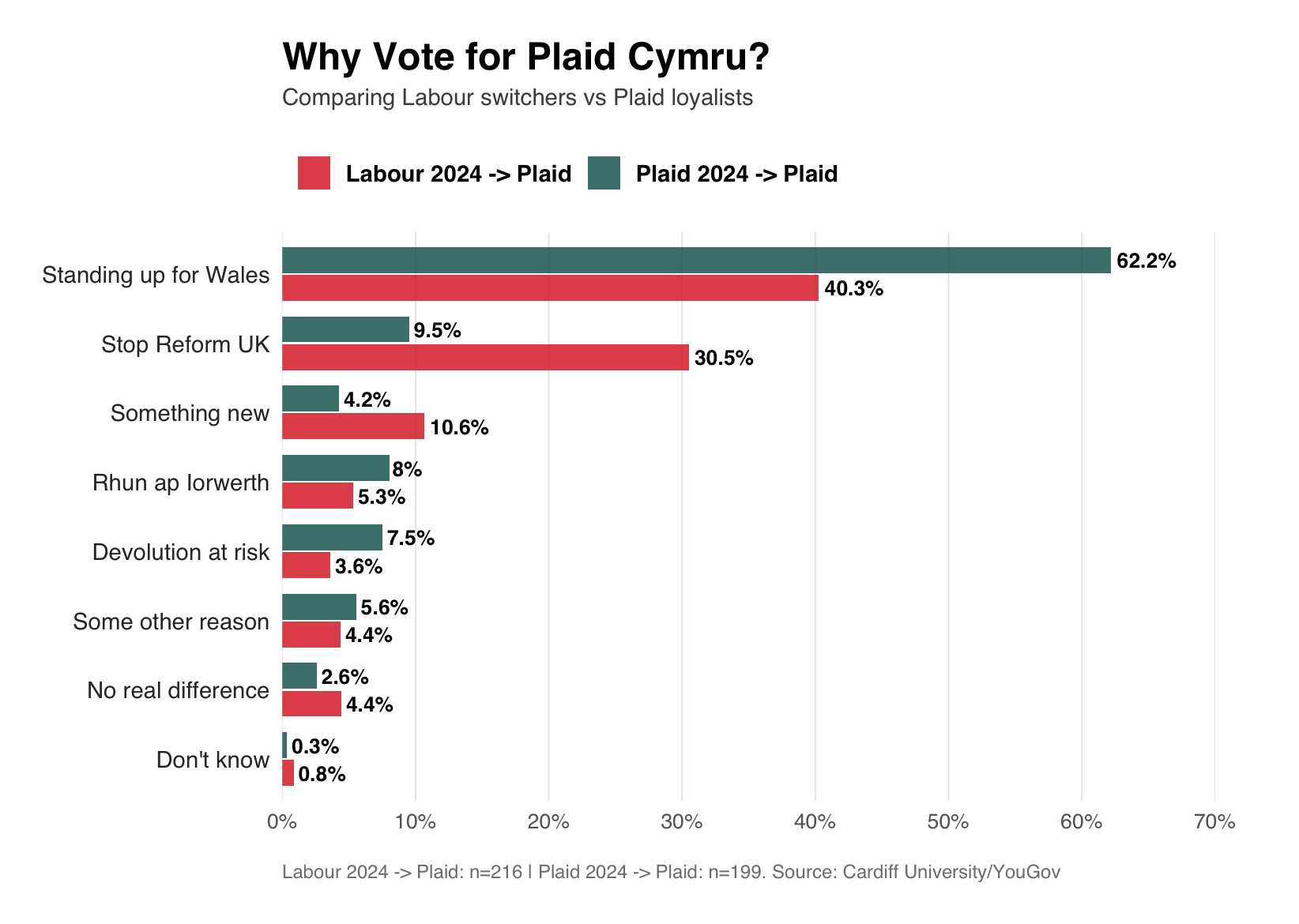

For Plaid Cymru, the contrast between Labour switchers and Plaid loyalists is stark but common themes emerge. People switching from Labour are heavily motivated by tactical considerations: 30.5% cite “They are best placed to stop Reform UK” compared to 9.5% of Plaid loyalists. This suggests a significant portion of Labour’s former vote is consolidating behind Plaid for defensive reasons rather than positive enthusiasm for Plaid itself. Yet Labour switchers aren’t purely tactical. Even more Labour switchers (40.3%) cite “standing up for Wales” as their primary motivation. This is an issue which Welsh Labour have arguably ‘owned’ for the entire devolution period, making the recent collapse in perception on this issue all the more remarkable. This combination indicates that Plaid’s consolidation of the Welsh-identifying progressive bloc combines defensive tactics with genuine belief that Plaid better represents Welsh interests.

Figure 4.

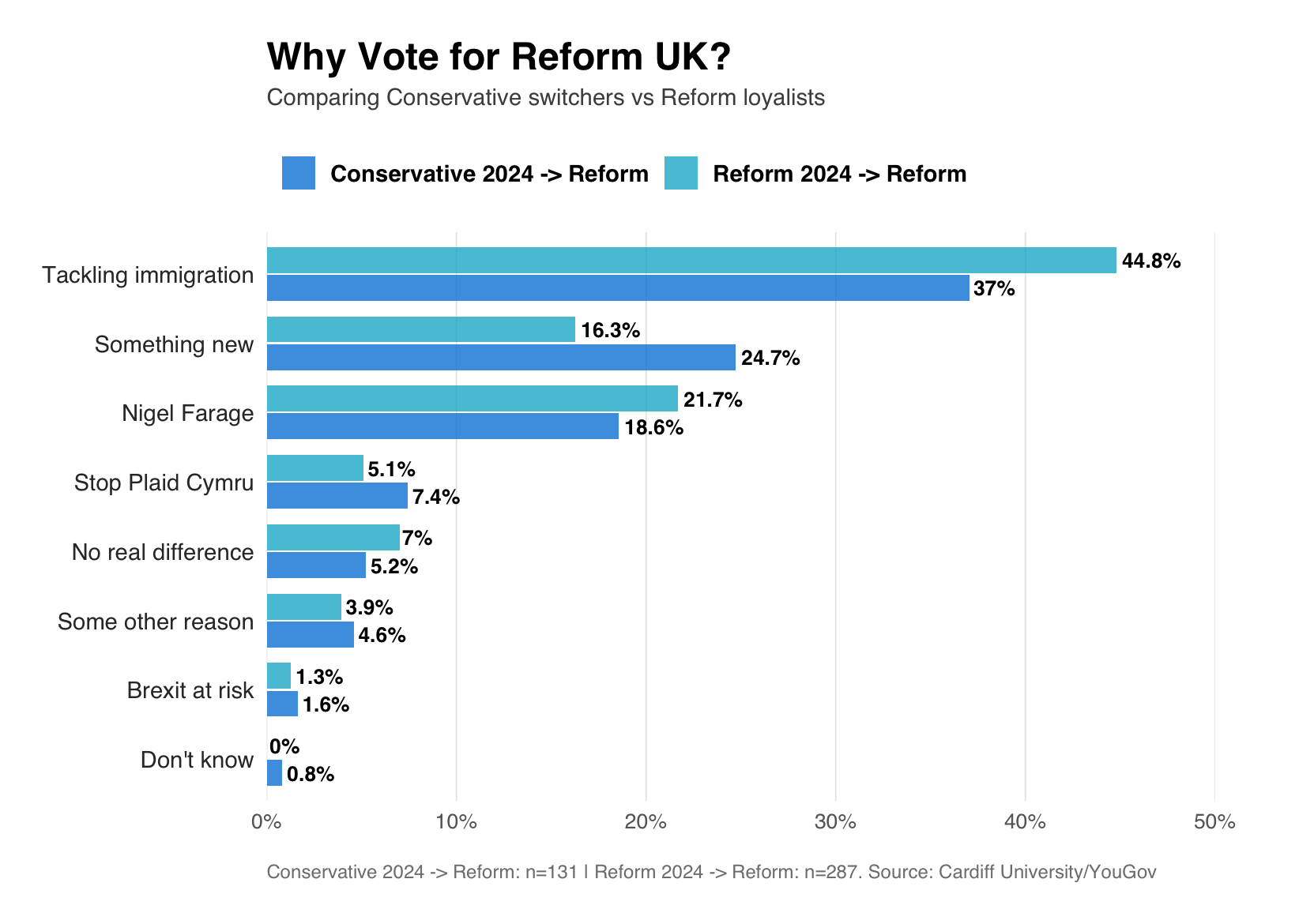

Reform UK switching shows a different pattern. Conservative switchers are significantly more likely to select protest motivations: 24.7% choose “something new” compared to 16.3% of Reform loyalists. Immigration remains the dominant issue for both groups (Conservative switchers 37%, Reform loyalists 44.8%), but the gap suggests loyalists are more ideologically committed while recent switchers include a substantial protest component. Leadership matters more for Reform than Plaid. Nigel Farage registers strongly among both Conservative switchers (18.6%) and Reform loyalists (21.7%), underlining the extent that his personal brand is central to the party’s appeal.

Figure 5.

Wales’s Semi-Distinct Realignment

Evidence of a political realignment in Wales continues to grow: real world election results (multiple local by-elections, and the Caerffili by-election) and multiple survey datasets from a variety of different providers point to a very different Senedd election in 2026. What generates genuinely autonomous Welsh dynamics is the progressive bloc. England’s disaffected Labour voters are increasingly drifting to the Greens or Liberal Democrats. Wales’ progressive voters have a credible alternative in Plaid Cymru, but specifically in devolved electoral competition, where the choice is about Welsh governance and Plaid can credibly claim to fight for Welsh interests within Wales.

This creates a bifurcated realignment with different mechanisms on each side. Reform’s consolidation of the British-identifying right reflects British politics playing out in Wales. Plaid’s consolidation of the Welsh-identified left reflects Welsh politics asserting autonomy within the devolved electoral context.

For the first time in a century, Welsh Labour faces the prospect of opposition or junior coalition partnership. That prospect, more than any survey, signals how profound this realignment truly is. The bloc structure that has organised Welsh politics for decades persists, but the hierarchy within those blocs has been overturned.

________________________

*This surpasses Scottish Labour’s worst ever polling figures of 11% in September 2019.

**We exclude the Liberal Democrats from this analysis largely due to small sample sizes. However, the party is the only one to consistently switch between blocs in terms of voter identities and attitudes. That said, more recently the party’s views on Brexit have placed it firmly in line with the progressive bloc of parties.

***If we separate voters born in Wales and born in England, the patterns are even more stark. For more on interaction of British identity and place of birth see here.

****We focus on these parties because they are the primary beneficiaries of current switching patterns and the two largest parties. Small sample sizes for other parties also makes the analysis less certain.

________________________

Basic cross tabs and raw data available here: https://github.com/jaclarner/Cardiff-YouGov_Dec25/blob/main/cross_tabs.pdf

- March 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- December 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Reform UK

- Rugby

- Senedd

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections