Habitual Petitioners: John and Jane Danyell

19 February 2024In this blog post, Lloyd Bowen, Reader in Early Modern and Welsh History, writes about an inveterate Elizabethan petitioner who was incarcerated for forging the earl of Essex’s correspondence.

In recent years my research has become increasingly concerned with the nature and dynamics of petitioning in early modern Britain. From the medieval era to the present day petitioning has been an accepted way for the comparatively powerless to speak to authority, and a means by which people can communicate their tribulations, suffering, and woes and, potentially, also their grievances, to those who govern them. I was involved in a major AHRC Project which catalogued, digitized and made publicly available petitions (and much other material) from veterans, widows and orphans who had been left in dire straits by the violence and disruption of the mid-seventeenth century British civil wars. These documents were usually framed as appeals for money to local magistrates, parliament or the king. Petitioners usually sought an annual pension which would help them to make ends meet. I located and transcribed many hundreds of such petitions from impoverished, wounded and destitute victims of the war. In so doing, I became interested in the process of petitioning itself and in the question of who ‘authored’ these documents, as they were often presented on behalf of individuals who were illiterate. I wrote a blogpost on this subject for the project website, and expanded this discussion into a chapter on authorship and genre in veterans’ petitions which will be published as part of a collection edited by Brodie Waddell and Jason Peacey in the spring of 2024.

Waddell and Peacey ran their own splendid project on early modern petitioning which has made nearly three thousand petitions from seventeenth-century England freely available via the Institute for Historical Research. Among their number are seven petitions from two individuals who particularly interest me, and who I have been running to ground partly via their many surviving petitions: John Danyell and his wife Jane. I am in the early stages of a research project on the Danyells and their petitionary lives, but their story is a remarkable one that casts much light onto the political dynamics of late Elizabethan and early Jacobean England and on the processes of petitioning.

John Danyell was a relatively minor Cheshire gentleman who was born around 1545. He came to Court and entered the service of the Irish nobleman, Thomas Butler, earl of Ormond. There are suggestions that Danyell entered the perilous field of Elizabethan espionage, infiltrating Catholic Irish groups who were plotting Elizabeth I’s downfall but, unfortunately for my purposes, this seems to have been a namesake and not the Cheshire gentleman. Our John Danyell did move in Court circles, however, and while at Court in the 1590s he met a fascinating woman, Jane de la Kethulle.

Jane was the daughter of François de la Kethulle, a prominent leader of the Protestant Dutch revolt against Spain in the 1570s and 1580s. Not long after François’ death in 1585, Jane fled to England as something of a religious refugee, later describing how she came ‘into the blessed harbour of this realme as the only refuge for … dystressed strangers’. Once in England, Jane entered the service of Frances Walsingham, daughter of Elizabethan spymaster, Sir Francis. In 1590 Frances controversially married the royal favourite Robert Devereux, second earl of Essex. And it was as the countess of Essex’s servant that Jane encountered one of the minor members of the earl’s retinue: John Danyell. The two were married in 1595 even though John was perhaps twenty years older than his bride, which was far from normal at this time.

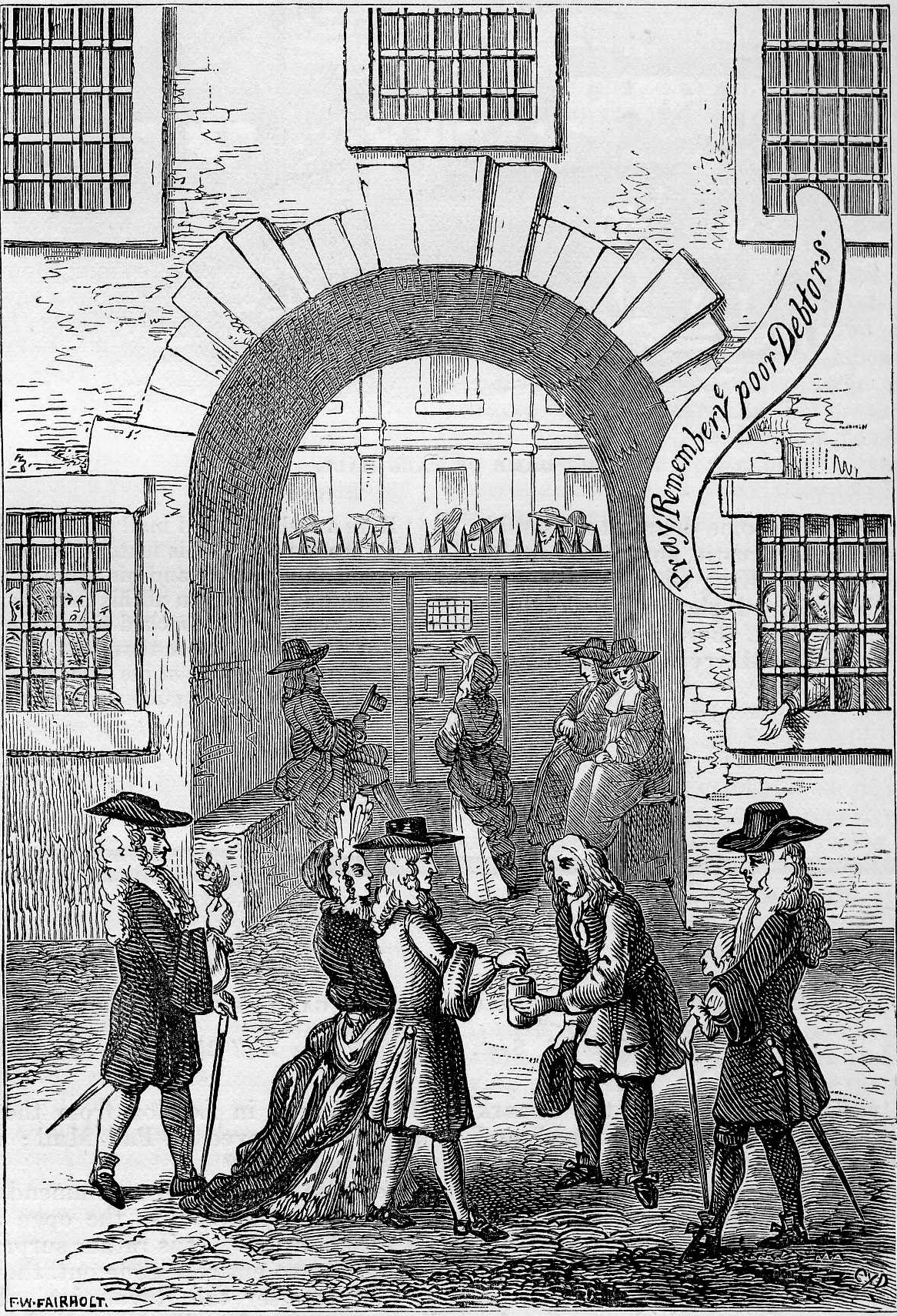

Essex was a controversial figure who would end up rebelling against the queen in 1601 and being executed for treason. The Danyells’ troubles began before this time, however. In 1599 Jane discovered a casket of letters beneath her mistress’s bed and turned them over to her husband. This correspondence must have been controversial, perhaps detailing some of Essex’s discontent with the queen, or perhaps they contained salacious details of Countess Frances’s love life. Whatever their contents, John Danyell saw in them a way to address a perennial concern of his: a lack of money. He used the letters as leverage to extort some £1,720 (a huge sum likely worth several hundreds of thousands of pounds in today’s money) from the countess. However, following Essex’s fall in 1601 the countess turned the tables on John, and he was prosecuted for deception and counterfeiting in the court of Star Chamber, a powerful tribunal with a fearsome reputation which dealt with high-profile cases such as Danyell’s. The court found against him and imposed a devastating punitive sentence: John was to be imprisoned for life and he had to cough up an enormous fine of £3,000, a sum that was clearly well beyond his means to provide. John’s long residence as an inmate of the Fleet Prison in London now began, as did the flood of petitions which he and his wife addressed to the great and the good of Elizabethan and Jacobean England over the next five years.

These petitions survive among the State Papers at The National Archives in Kew, and they throw a fascinating light onto the process of petitioning and representation in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. These documents covered a wide variety of requests: John Danyell asked that be released from his confinement; that his fine be remitted; that he be given paper and books; that his estate not be broken up; and many other things besides.

Like my civil war petitions, Danyell petitions are also problematic documents in terms of their ‘authorship’, with representations in Jane’s name which are clearly written in her husband’s idiosyncratic hand. Moreover, the texts are often quite formulaic, with John employing standard phrases about the injustices he had experienced and his outrage at being treated in such a manner ‘in a countrye where justyce and Chrystyan relygyon ys soe much esteemed’. Such formulae draw our attention to the fact that the constant repetition of a message in petition after petition was perhaps as important as rhetorical creativeness in such addresses.

The Danyells’ petitions also come in a variety of forms, with John’s original drafts that mean we can see him composing petitions before deciding on their final form; addresses in Jane’s own hand with her distinctive English spelling; and also beautifully rendered documents which were produced at some cost by a professional scribe – often these were high status petitions to the monarch. These petitions were also not simply ‘one-way’ documents of entreaty, however, but were rather texts of interaction, with answers and comments endorsed on them by the recipient; answers which often informed the Danyells’ next petitionary pitch. One can sometimes almost hear the exasperated sigh which must have greeted yet another Danyell petition arriving on their desk, as in Lord Chancellor Ellesmere’s observation on one of John’s addresses: ‘I have often answered hym, this [petition] is too generall [and] I cane do nothing for hime’.

The Danyells’ petitionary addresses also morph into striking longer form narratives, justificatory appeals and semi-autobiographical treatises. Some of these presentation manuscripts were designed for publication and contain draft title pages, addresses to the reader and directions to a prospective publisher. They have titles such as ‘The Unexpected Accedents of my Casuall Destyny’, ‘The Varyable Accedents in a Pryvat Mans Lyffe’ and ‘A True Declaration of the Misfortunes of Jane Danyell’. These are fascinating texts which have an intriguing relationship with the body of petitions, often drawing on similar incidents, deploying familiar phraseologies and adopting analogous subject positions as those found in the Danyells’ petitionary addresses. There is an interesting thread to be developed here on the connections between petitions and early forms of autobiography.

John Danyell was eventually released from prison by King James I, but his health seems to have been severely affected by his years in gaol and his estate was decimated by the Star Chamber fine. He died in Westminster in April 1610, leaving an heir who was only thirteen. At this time, Jane was on the continent, and, after hearing the news of her husband’s death, she wrote to her brother-in-law that ‘I will coomme shortly to performe my dewty towardes hym [John] and to my children after his deathe as I have donne in his lyfe tyme’. Jane herself probably died a few years later.

The Danyells’ archive is extensive and I am just beginning to navigate it. Nevertheless, it clearly offers much of interest and diverting new avenues of research for those studying petitions and politics in early modern England. As such, these documents give us a unique insight into the dynamics of addressing power and requesting relief in Elizabethan and Jacobean England.

Further Reading:-

Lloyd Bowen, ‘Genre, Authorship and Authenticity in the Petitions of Civil war Veterans and Widows from North Wales and the Marches’, in Brodie Waddell and Jason Peacey, eds, The Power of Petitioning in Early Modern Britain (London, 2024).

Geoffrey Chester, ‘John Daniel of Daresbury, 1544–1610’, Proceedings of the Historical Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 118 (1966), pp. 1–16.

Andrew Gordon, ‘Recovering Agency in the Epistolary Traffic of Frances, Countess of Essex and Jane Daniell’, in James Daybell and Andrew Gordon, eds, Women and Epistolary Agency in Early Modern Culture, 1450–1690, (London, 2016), pp. 182–206.

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History