An empire for the Enlightenment: Britain, Quebec, and the American Revolution

11 December 2023

As Ashley Walsh explains in this blog post, it is a counter-intuitive feature of the Enlightenment that it could be intolerant. We tend to associate the Enlightenment with religious toleration and ‘liberal’ pluralism. By contrast, we count persecution as one of the worst excesses of the Reformation and early modern European wars of religion.

In eighteenth-century Protestant confessional states like Britain and Prussia, the Enlightenment inherited from the Reformation a deep-seated fear of the political claims of the supremacy of the papacy and the Catholic hierarchy of bishops and priests. But, in my forthcoming article ‘The Quebec Act (1774) and the Hanoverian-Church-State Relationship’ in English Historical Review and my new book project — The Enlightenment and Catholic Emancipation in Britain and its Empire, 1745-1829 – I explore how global wars and imperial expansions of the eighteenth century occasioned a remarkable change in attitudes.

Until the 1770s, eighteenth-century Britain was uncompromising in its opposition to Catholicism. Memories of James II on the British Isles and Louis XIV in France encouraged Britons to regard Catholicism as a prop for absolutism. In the aftermath of the Revolution of 1688 – a bloody revolution that was not so ‘Glorious’ for Catholics in Ireland and Scotland – parliament had passed antipopery laws that deprived Catholics of civil liberty in the name of state security.

To be a Catholic was to un-subject oneself. Catholics refused to recognize the sovereignty of the crown and parliament by rejecting the royal supremacy enacted by Acts of Supremacy of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. You can’t serve two masters, the argument ran. Suspicion of Catholics’ superstitious fealty to their priests and the spiritual pretensions of the pope to dispense with the laws of temporal monarchs meant that Catholics could never be regarded as loyal subjects. The theorist of toleration, John Locke, saw no contradiction in denying Catholics freedom of worship because their papalism made them uncivil.

Nor were these views limited to the British mainland. Across the Atlantic, the puritan heritage of the American colonists encouraged them to share with their brethren in Britain a deep fear of Catholicism. Popish priestliness and the temporal tyrannies it reinforced were the antithesis of the British Protestant liberty in whose name Americans would revert to revolution in 1776.

One of the outcomes of the global Seven Years War (1756-73) was the British conquest of the French province of Quebec. When Britain had previously conquered Catholic territories, such as Acadia, the populations had been small, and it had been possible to expel them. But Quebec was substantially larger. The British government faced a problem. Either it could enforce all its Reformation and antipopery laws in the new province, or it could find a pragmatic modus operandi. It chose the latter.

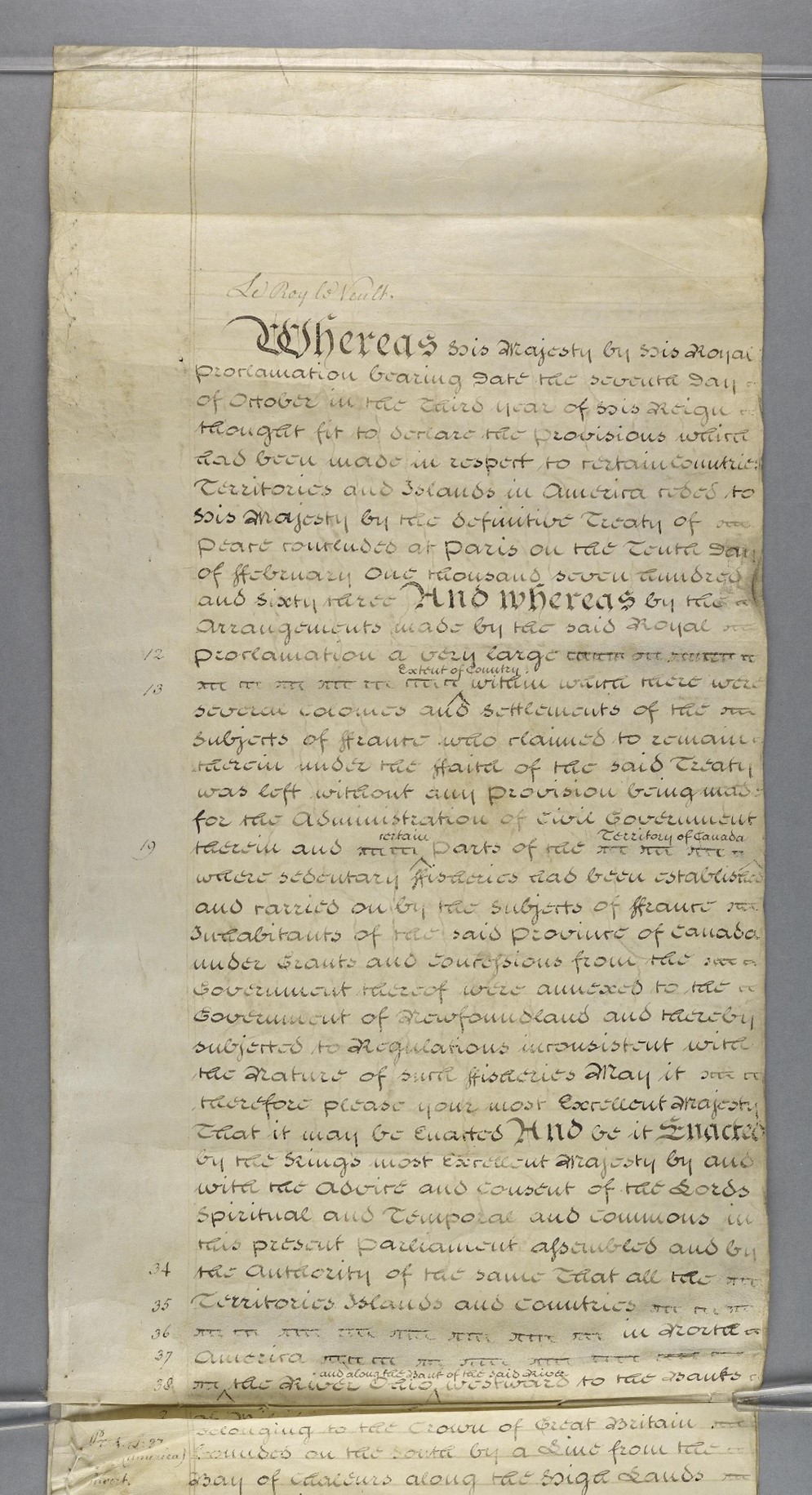

In the Quebec Act (1774), the culmination of nearly 15 years of ministerial, parliamentary, newspaper, and pamphlet debate, Westminster continued the use of the French civil code and seigneurial system of land tenure alongside English criminal law. Judging the French ill-suited to representative politics, and troubled by colonial assemblies in America, the government did not create an elective body in Canada. To foster Canadian fealty, Westminster removed references to Protestantism in the new oath of allegiance and provided free Catholic public worship, including the rights of priests to tithe and a superintending bishop.

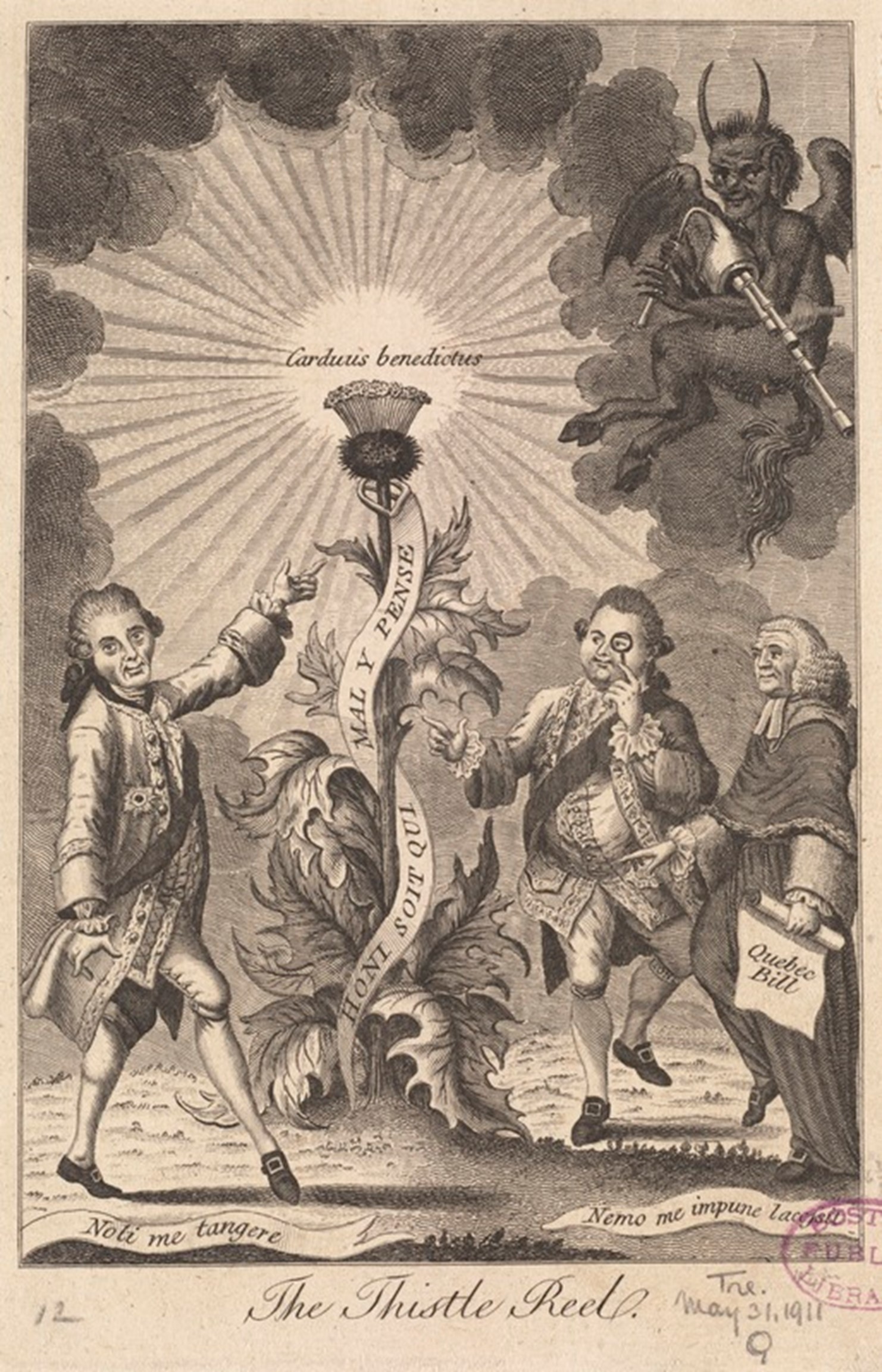

To Britons and Americans, these provisions put French absolutist garb on Catholic tyranny. Along with the Boston Port Act, Massachusetts Government Act, Administration of Justice Act, and Quartering Act, the Quebec Act was the fifth of the ‘Intolerable Acts’ of 1774 that provoked the American Revolution.

Within what remained of the British Empire after 1776, the Quebec Act was the first of several reforms that eventually culminated in Catholic emancipation in 1829. To tremendous opposition, this process ended the status of imperial Britain as a Protestant confessional state. The Catholic relief bills of the 1770s resulted in the Gordon riots (1780) when the great Enlightenment historian, Edward Gibbon, quipped that ‘forty thousand Puritans have started out of their graves’ and when the Anglo-Irish Enlightenment thinker, Edmund Burke, nearly lost his life for his support for Catholic relief.

Historians characterise the Quebec debate as one between the wise, Enlightened governors of an increasingly diverse empire, fashioning a pacific policy to secure freedom and loyalty among conquered subjects, and the atavistic, intolerant Protestant proto-nationalism of the zealous mob. However, while I was researching my forthcoming article, I found that closer inspection of ministerial archives, parliamentary debates, and newspapers and pamphlets reveals a much more sophisticated picture. As much as its supporters, opponents of the Quebec Act drew from complex Enlightenment arguments to defend their proposals for circumscribed Catholic toleration. The Quebec debate was, first and foremost, one about contrasting Enlightenment visions of empire.

The opposition to the Quebec Act rehearsed the classic Enlightenment anticlerical critique of ‘priestcraft’ to support their claim that a Catholic hierarchy with public offices threatened the security of the state. Popes and priests suppressed political and religious liberty by the dominance of church over state. As Sir James Marriott, a former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, argued in a pamphlet against the legislation, the ‘legion of ecclesiastics may prove as powerful in subverting, as in maintaining princes and states’. Catholics should be allowed inward freedom of conscience, but no bishop and tithing priests. It was folly to tolerate the intolerant.

Using ideas of political economy associated with the Scottish Enlightenment, some opponents cast Catholicism as the inverse of commercial modernity. They claimed it was a religion replete with unproductive holy days and riddled with religious institutions that gobbled up the wealth of the nation. Moving a parliamentary motion to repeal the legislation, Charles Pratt, Earl Camden and a former Lord Chancellor, argued that Catholicism had created a Canadian polity ‘repugnant to the spirit of commerce, and abhorrent to the feelings of British subjects’.

Supporters of the Quebec Act accused their opponents of precisely the intolerance with which they had charged the popish. The dark times of superstition were gone, they claimed. Catholicism was an increasingly civil faith. It was not simply politic and just to be generous to conquered Catholics, but it was also safe. Pope Clement XIII had declined to recognise the Jacobite succession following the death of the Old Pretender in 1766. Supporters of the Quebec Act pointed to the Catholic Enlightenment in Britain in which ‘Cisalpine’ thinkers drew from medieval conciliarism to limit the temporal claims of the pope over monarchs in opposition to ‘Ultramontane’ arguments for the unrestricted power of Rome.

Other supporters of the Quebec Act set British imperial policy in European context. The Seven Years War had also involved the Silesian Wars in which Protestant Prussia had conquered the province of Silesia from the Catholic Habsburgs. The Enlightened absolutist, Frederick the Great, had there provided Catholic freedom of worship, expressing his commitment to his new subjects in the majestic Baroque opulence of St Hedwig’s Cathedral in Berlin. James Usher, the Irish man of letters, noted in a pamphlet for Irish Catholic relief that the ‘protestant sovereigns of Germany accept the oath of fidelity of their catholic subjects as our own government has of the conquered subjects of Canada’.

Traditionally, historians have interpreted the process of Catholic emancipation between the 1770s and 1820s as a matter of imperial pragmatism. Catholic freedom was a prerequisite for modernising the Irish economy and governing an increasingly diverse empire. But, as my forthcoming article and book project will show, the Quebec debate and subsequent questions about Catholic relief draw our attention to much deeper problems that had their roots in both the Reformation and Enlightenment as the British confessional state traded its Protestant constitution for a pluralist one.

Written by Dr Ashley Walsh, Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History

If you want to know more about the research of Dr Walsh’s research, see Dr Ashley Walsh – People – Cardiff University.

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’

- Collaboration across the pond: uniting histories of religious toleration in the American Revolution and European Enlightenment