Keeping It Real. Or What Was Stalinism, Exactly?

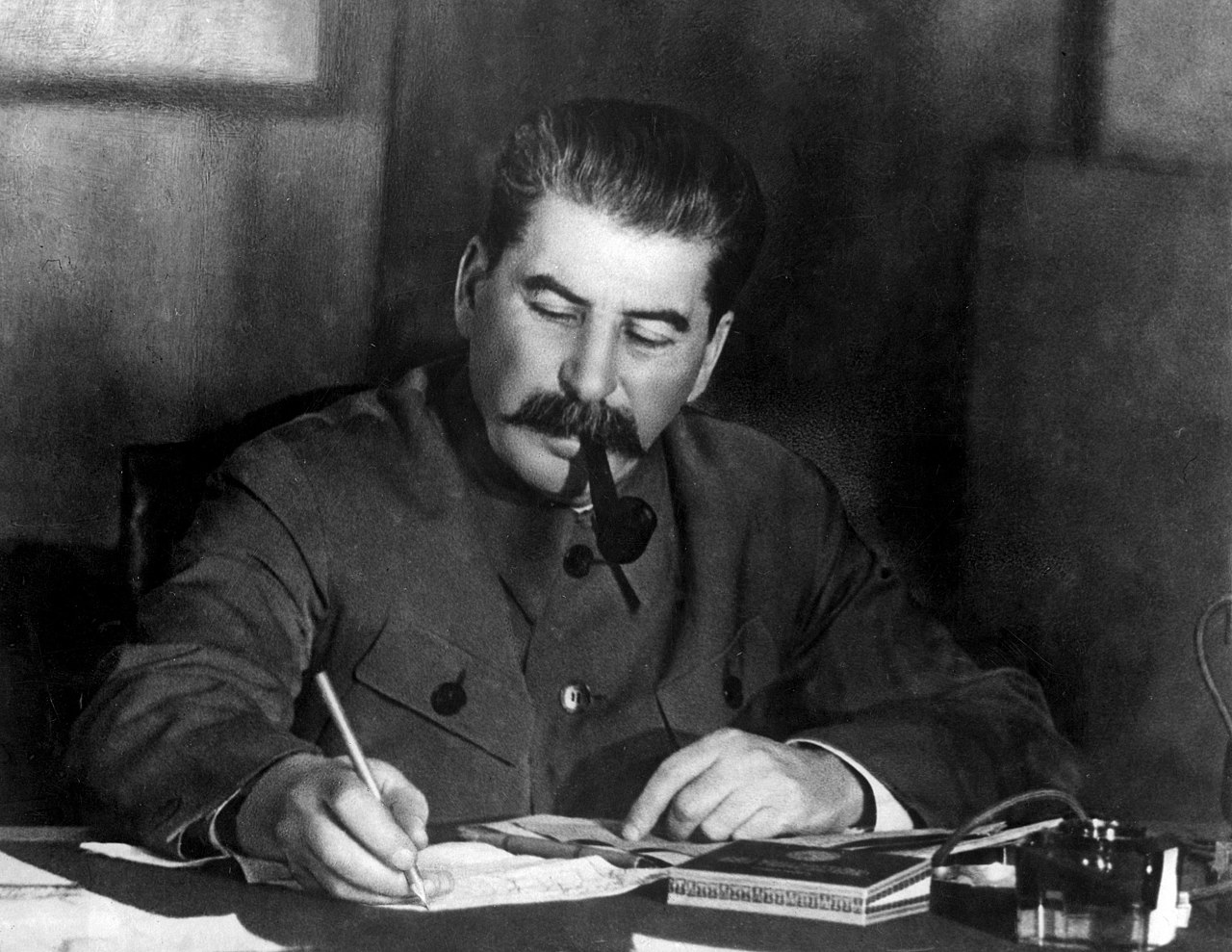

11 March 2024In his post, James Ryan, Senior Lecturer in Russian History, asks what is ‘real’ about Stalinism.

There once was a peasant whose worldly possessions, apart from his home, amounted to a bed, a little grain, and a mirror. His name we do not know, nor where he lived. But on the evening of 6 April 1928, this peasant was mentioned in a major speech in Moscow delivered at a joint plenary session of the Communist Party’s Central Committee and Central Control Commission (these sessions were a lot more interesting than they sound!). The speaker was Anastas Mikoian, the Soviet trade commissar from Armenia, one of Stalin’s loyal lieutenants. Mikoian was looking for an anecdote to illustrate what he and the Party saw as the regrettable ‘excesses and distortions’ then occurring in villages all over the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), as state agents pressured villages to deliver their grain and taxes. His mirror inventoried for confiscation, our unnamed peasant decided to smash the glass in protest: if he could no longer use it, then the state should not have it either.

The point of this anecdote is that mirrors serve as a symbolic shortcut to the very nature of Stalinism. Mirrors allow us to face ourselves. They help distinguish what is real and substantial from what is phantasmagorical or fantastic. Then again, because mirrors merely reflect, they do not allow us to see beyond our own mirror-image.

I am currently writing a book titled The Limits of Utopia: An Intellectual History of Soviet State Violence, 1917-1939. Recently, thanks to a scholarship funded by the Gerda Henkel Stiftung in Düsseldorf, I was able to turn my attention to the period in Soviet history known as the ‘Great Break’ (the великий перелом, in Stalin’s original Russian words), which I’ve widened slightly to the years 1928-1932. These are the years when Stalinism emerged in the USSR, when the Soviet economy and society were transformed by state-directed industrialization and the forcible collectivization of agriculture — all in the name of reaching socialism so rapidly that time itself seemed to compress.

Writing about this period, I have tried to make sense of how the ruling Communist Party made sense of these years of astonishing and violent upheaval. But as I read through the mass of secondary literature and the record of party thought — some of it published, some of it gleaned from previous archive trips to Moscow — I realised two things. First, we don’t have a very precise sense of what Stalinism actually was. As the historian Gábor Rittersporn puts it, most scholars ‘carefully avoid’ an exact description. And second, what it was may well hinge on its relationship with reality. In fact, I think the key to understanding Stalinism might be ontology, or the study of existence: Stalinism can be defined less by its actual policies (although those matter) and more by its frayed relationship to what is real, to what exists beyond its own reflection. This semester, as we offer a new undergraduate module at Cardiff specifically devoted to Stalinism, I’m looking forward to exploring what this might mean with my students.

My way of doing intellectual history — part instinctive, part deliberate — is to look at words and try to see patterns of meaning, those ‘key words’ that let us into the mindset and emotional disposition of those I write about. I noticed how ‘realism’ (реализм) and ‘reality’ (реальность) and variations thereof, such as ‘in reality/in fact’ (в действительности), and ‘unreal/unrealistic’ (нереальный), appeared consistently and centrally at critical moments during the ‘Great Break.’ The repetition of such works suggest how the emergence of Stalinism was rooted in the question of whether the party would remain tethered to reality, to ‘life itself.’ Stalinism required a disruption of conventional assumptions. But could the party achieve a socialist ‘break’ without entering the realm of fantasy? This question provided the linguistic register for inner-party discussion, debate, and dispute in 1928 and 1929 and beyond. And it was in these terms that Stalinism, as such, took shape — because of the Stalinists’ insistence that what they claimed was possible was, in fact, materialising. At the party’s pivotal Central Committee Plenum in November 1929, the various doubts about policy voiced by some party leaders were noted and each ritually countered with the same phrase, ‘in actual fact’ (на самом деле), which proclaimed that the party leadership’s unbounded optimism had been ‘verified by life itself.’

To see Stalinism through the lens of realism is both familiar and novel. It has long been recognised that Stalinist economic plans were utopian projections that bore little relation to reality. The most obvious association between Stalinism and realism is ‘Socialist Realism,’ formally adopted as the requisite Soviet literary (and broader artistic) form in 1934, which portrayed Soviet reality not so much as it was but as it was becoming. Socialist Realism, according to Evgeny Dobrenko, coloured all Stalinist discursive forms, not only artistic. But Stalinist realism tells us other things too.

The question of the real and the fantastical is a question about what is possible. It is about boundaries (whether to recognise or ignore them), and it is about the trope of sight and vision, which was central to the language of Stalinist transformation. Can you not see socialism emerging before your very eyes? If not, it wasn’t your eyes that were the problem but your lack of belief. And yet, like all utopian endeavours, Stalinism was characterized by a palpable tension between idealism and realism. As my research is exploring, the pre-war Stalin era in Soviet history was largely one of crisis brought on by a combination of unrealistic demands and weak governing infrastructure, resulting in brutal policies that were as much reactive as intentional. Many communist activists learned that the way to make the impossible real was through violence.

Contrary to what some might think, there has been no return to Stalinism in Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Nonetheless, if the historical phenomenon of Stalinism hinges on the question of reality, then its resonance in our own day is, in fact, only too real. Whether we think of the global climate crisis or ‘fake news’ or the potential of AI, or the nature of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or Israel’s military bombardment of the Gaza Strip, what is it that we see? What is obscured or unseen? What is really ‘real,’ and what do we do when others deny (our) reality?

The question of the real is already one of the great challenges that humanity confronts in the twenty-first century.

Works Mentioned:

- Gábor T. Rittersporn, Anguish, Anger, and Folkways in Soviet Russia (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014)

- Evgeny Dobrenko, Political Economy of Socialist Realism, trans. by Jesse M. Savage (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007)

- P. Danilov et al (comps), Kak lomali NEP: Stenogrammy plenumov TsK VKP(b), 1928-1929 gg., Vol.5: November 1929, Moscow: Materik, 2000.

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’

- Collaboration across the pond: uniting histories of religious toleration in the American Revolution and European Enlightenment