Tubey or not tubey, that is the question…

5 February 2020‘There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.’ (Hamlet, Act 2 Scene 2)

Every object has its own story to tell. Some stories are happy, some are tragic, and some are simply a mystery. In this post, I will share details of an unusual object and reflect on my thoughts about its treatment.

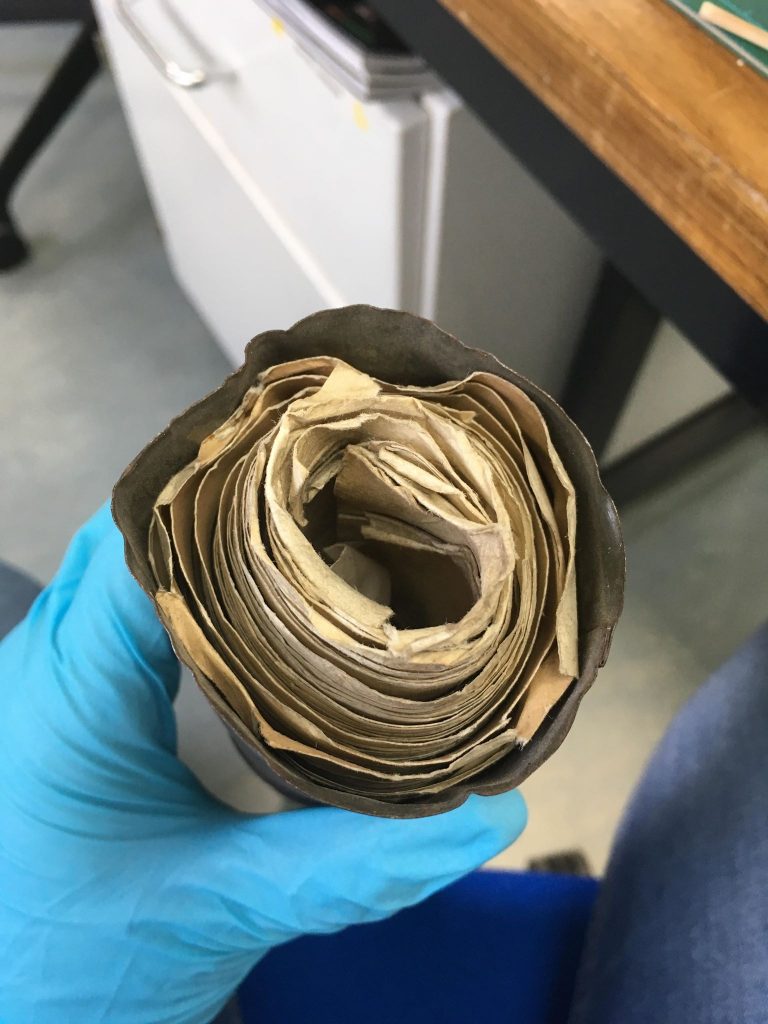

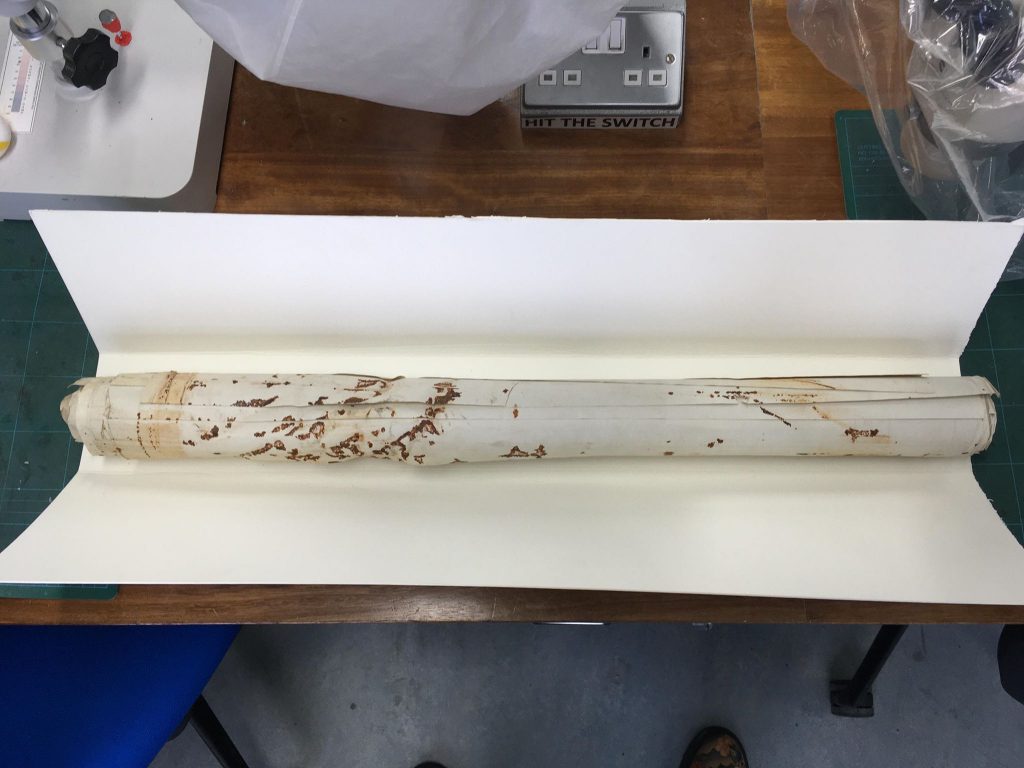

Last autumn I began work on a new object in the university lab – a tin-plated tube, about 80cm long, sealed at one end (the cap was missing). It was partially crushed, distorted and corroded. Visible from the open end was a large roll of paper wedged inside the tube.

The owner, Y Gaer (formerly Brecknock Museum), had no details about its history and no knowledge of its contents. A typewritten label stuck to the tube read ‘Plans and Correspondence’, but this offered little insight because its header was heavily stained and therefore unreadable. The museum’s curator requested that I find a way to remove and treat the paper contents as needed. The tube was regarded as a secondary concern – if it needed to be sacrificed to save the paper, it was instructed that this would be acceptable.

However, this did present something of an ethical dilemma. Conservation ideals typically require objects to be subjected to minimally interventive treatments. Is it right to permanently alter or ‘damage’ one component of an object in order to treat another? There was no prior knowledge of what was on the paper. The label seemed to be more than a hint that the contents were plans of some sort – however, this could not be relied upon as containers are often re-purposed for other uses. The tube might have been sacrificed only to discover that it contained merely a blank roll. Indeed, was it possible that the tube could in fact have more intrinsic historical value than its contents?

Peering inside the open end of the tube revealed what appeared to be a black border line printed on one layer of the paper roll and additionally, a glimpse of something metallic – possibly a paperclip or staple – on the innermost layer. At that juncture, it seemed more likely that the paper would be of further interest. Research into the tube’s manufacturer, as well as its form and size, added weight to the theory that the paper might indeed be technical blueprints of some sort.

The crushed section of the tube was badly damaged and there were small holes in the metal. While it was impossible to see very far inside it, there was some visible internal corrosion. This was concerning given that the paper roll was pressed very tightly against the metal. It was clear that the paper would need to be removed, but given that it was completely stuck – how?

As a first step, I tested out solutions that would involve minimal intervention. I experimented with inserting barriers between the paper and the tube to reduce friction, and also coiling the paper more tightly with a giant set of bamboo tongs in the hope of ‘easing’ it past the crushed section. Unfortunately, neither was successful – it could not be moved even a millimetre. Any attempt to manipulate tools in the crushed section to create space, or guide one past the damaged area proved fruitless. I realized that continuing along that path was likely to lead to the paper tearing. By now, it was obvious that Tubey would not be giving up its secrets without a fight!

There was nothing else for it… it was time for some surgery.

The most obvious solution was to cut through the tin. The thought filled me with dread. From the little I could see, there was no barrier between the paper roll and the metal, leaving hardly any room to work. This meant any cutting would have to be carried out partially blind and with a high risk of damaging the paper. However, switching my focus to the tube, I realized that it had been made from a flat sheet of metal formed into a cylinder with the two free ends locked together by means of a tight ‘Z’-shaped, folded seam. If I could find a way to prise this seam apart without cutting the metal, then potentially I could retrieve the paper and save the tube without causing irreversible damage.

The seam at the open end of the tube had been treated with solder that would need to be removed first. I considered melting it with a soldering iron. However, I could not be sure of the solder type used and the tube was quite thin. Again, there was a high risk of damaging the contents. The thought of ending up with some important historical documents perforated along one side like a paper doily was giving me nightmares.

I needed a hand tool with a with a broad but sharp blade. In the end I settled on a curved lead knife; a tool more commonly used to cut lead came for stained glass work. It took me several hours to gradually release the seam, working my way down to the crushed section with the knife and a mallet. I had hoped that once I had gone beyond that narrow point, I would simply be able to remove the roll. However, Tubey had other ideas and refused to let go of its precious cargo. There was no choice but to carry on down the entire length. Once I had reached the end, the reason for this stubbornness became clear. What I had not been able to see previously was the extensive corrosion affecting most of the inside. The outermost layer of the paper was firmly stuck to the metal and required gentle prising off with the help of a bone folder. Once released from the tube, it was then left to relax for several days until it could be gradually unrolled. After that, I took the paper to Glamorgan Archives to humidify and flatten it… but that’s another chapter in Tubey’s story.

Nearly there…

And it’s finally free. Phew!

…In the meantime, just what was written on that roll of paper?

It turned out to be twelve copies of architectural plans for Llanfaes Bridge in Brecon (which still exists) dating back to the 1940s, along with several paperclipped letters and telegrams which revealed that the plans had been posted to the local council offices by the county surveyor. From his correspondence, it appears that this was the second time he had dispatched them – the first set having gone astray. We will never know if this new set ever reached their intended recipient. How the tube came to be crushed, or how it found its way to Brecknock Museum also remains a mystery…

When I started working on the tube, it was very much an unknown entity. No one had any idea of its history or what the contents might be, and thus it was difficult to feel certain that I had decided on the right course of action. Although forcing the tube open did not initially sit well with my ‘conservator mindset’, in hindsight I came to realise that it was not a bad thing. It was done as a last resort because the plans could not have been safely retrieved in any other way; and therefore I am satisfied that it was ultimately a good decision for this object.

- March 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (6)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (8)

- March 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (3)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (4)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (5)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (2)

- March 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- August 2018 (2)

- July 2018 (5)

- June 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (3)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (3)

- May 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (4)