The Polaris expedition and the problem of bias in Arctic exploration history

21 November 2022

By Nanna Kaalund

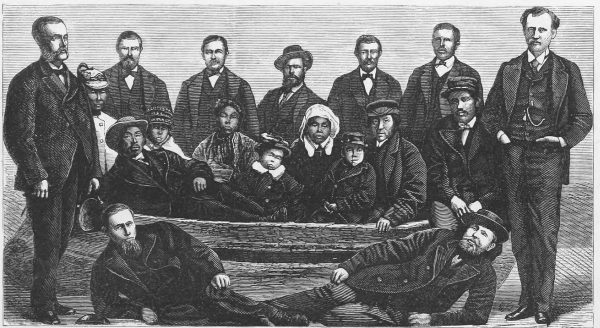

In April 1873, the whaling ship Tigress discovered twenty people drifting on an ice floe off the coast of Newfoundland. Those rescued were crewmembers from the Polaris expedition, which had left the United States in 1871 with the aim of reaching the North Pole. The ice-floe crew became an immediate media-sensation as soon as they landed in Newfoundland. It was an extraordinary story. Those rescued had survived 190 days on sheets of ice, drifting approximately 1500 miles during that time. That these people all survived was nearly as impossible, especially given that there were four young children among them. The local journalists interviewed several of the crew, and their articles were printed, and reprinted, in the national and international press. The survivors told of an expedition that had descended into chaos after the suspicious death of their commander Charles Francis Hall, and that the crew had become separated during a storm under equally suspicious circumstances. The ice-floe crew had only survived, the newspapers reported, due to the efforts of four Inuit explorers. They were Ipiirvik and Taqulittuq (known in the period as Joe and Hannah), a married couple from modern-day Canada, and Suersaq (known in the period as Hans Hendrik) and Mequ, a married couple from Greenland.

The Polaris expedition was the third time Suersaq had travelled as part of a North Pole venture, and Mequ’s second time. Ipiirvik and Taqulittuq were equally seasoned Arctic travellers and had worked with Hall for several years. Combined with the fact that the American newspapers documented the extraordinary efforts and abilities of the four Inuit explorers in 1873, it may seem surprising to contemporary readers that Ipiirvik, Taqulittuq, Suersaq and Mequ have not been memorialized in the history of Arctic travels in the same way as other explorers. In my article, “Erasure as a Tool of Arctic Exploration” published in the Historical Journal, I take the Polaris expedition as a starting point to ask questions about how and why master narratives about Arctic exploration have been written. When the Navy sought to manage public opinion regarding the Polaris expedition, they drew on strategies that were similar to those used by Hall.

When Hall first travelled to the Arctic in 1860, he had no experience or training to properly prepare him for Arctic exploration. Nevertheless, he convinced the whaling captain Sidney Buddington to let him travel on his ship to the Arctic. This was where Hall was introduced to Ipiirvik and Taqulittuq. The Inuit couple had previously visited England, and they both spoke English (1). Ipiirvik and Taqulittuq taught Hall to travel in the Arctic, but Hall succeeded in framing himself as an Arctic expert by rescripting and erasing their knowledge. As Hall wrote, “neither M’Clintock nor any other civilized person has yet been able to ascertain the facts. But, though no civilized persons knew the truth, it was clear to me that the Esquimaux were aware of it, only it required peculiar tact and much time to induce them to make it known.” (2). Inuit testimony was, Hall argued, only reliable when mediated by someone like him. This was the same argument used by the United States Navy when they sought to cover up the events of the Polaris expedition.

The rescue of the ice-floe crew was covered extensively in the press, as was the later investigation into Hall’s death and the misbehaviour of the crew. This coverage shows, in real time, how the Navy worked to rewrite history. As soon as the Navy were able to, they detained the ice-floe crew at the Navy Yard in Washington and forbade them from speaking to journalists. The early newspaper articles had drawn on interviews with the crew, including Ipiirvik. They had spoken of alcohol abuse, general bad behavior, and the possible murder of Hall. Those were difficult accusations to refute, especially given half the Polaris crew had been stranded on the ice-floe. It did not look good for the Polaris, and, by extension, the Navy. The venture had been sponsored by the United States government and was under the purview of the Navy, and charges of mutiny, poison, and drunkenness reflected badly on both the crew and the expedition organizers.

To sidestep these early newspaper reports, the Navy drew on a similar strategy as Hall. In their official report on the Polaris expedition, the Navy portrayed Ipiirvik as being unable to understand basic questions in English. Ipiirvik had lived in the United States for years, and spoke English fluently. But in making it seem as though Ipiirvik did not understand a simple yes or no question, the Navy portrayed Inuit testimony and Inuit knowledge as requiring translation by Europeans in order to be scientific or useful. With this line of argument in mind, the Navy contended that the journalists had failed to act as mediators in their interview with Ipiirvik. In the portrayal of his own work, Hall had portrayed himself as this kind of mediator. Thus, as the example of the Polaris expedition shows, the history of Arctic exploration has a built-in bias. It has centered the European and Euro-American explorers, and, in turn, has prioritized their representation of the Arctic. As the case of Tookoolito, Ipiirvik, and Hall shows, unpacking how the processes of nineteenth-century scientific knowledge-making were entrenched in imperialistic structures of epistemic and physical exploitation, allows us to unravel how these structures have continued to be reproduced in Arctic studies today.

If you want to read Nanna’s article on the “Erasure as a Tool of Nineteenth-Century European Exploration, and the Arctic Travels of Tookoolito and Ipiirvik” published in the Historical Journal, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X22000139.

(1) For more on the lives of Tookoolito and Ipiirvik, see: Sheila Nickerson (2002), Midnight to the North: The Untold Story of the Woman who Saved the Polaris Expedition, Putnam; Karen Routledge (2018), Do You See Ice?: Inuit and Americans at Home and Away, University of Chicago Press.

(2) Charles Francis Hall (1865), Life with the Esquimaux vol. I: 4.

Nanna Katrine Lüders Kaalund is a postdoctoral research associate at Aarhus University, Denmark, where she holds a Carlsberg Fellowship for the project “Economizing Science and National Identities: The Royal Greenland Trading Department and the Making of Modern Denmark and Greenland”. She previously worked at the University of Cambridge and the University of Leeds, and is the author of the book Explorations in the Icy North, which was published with the University of Pittsburg Press in 2021. Her research examines the intersection of Arctic exploration, race, print culture, science, religion, and medicine in the modern period with a focus on the British, North-American, and Danish imperial worlds.

- From the Floe Edge: Visualising Sea Ice in Kinngait, Nunavut

- Bridging Knowledge and Action: A Polish-Norwegian Perspective on Arctic Science-Policy Collaboration

- Unpacking the Motivation Behind Wintering at Polar Stations

- Working the Ocean’s White Gold: A Nutshell History of a Living Bering Strait Tradition

- Political Participation in the Arctic: Who is heard, when, and how?