Now the clapping has stopped: it’s time for a new pay settlement for care workers

13 August 2020This Thursday marks 11 weeks since people across the UK last broke out into applause for key workers. It would be easy to dismiss this weekly display of appreciation as a largely symbolic gesture; but it did inspire mutual recognition of a key tenet of this pandemic: though the crisis affects us all, the burden is not equally shared across society. Some people have been – and continue to be – disproportionately affected by the virus.

The important role played by key workers is not in doubt. And yet, it is well-documented that many of these workers are employed in relatively low-paid occupations – this is particularly true in the social care sector.

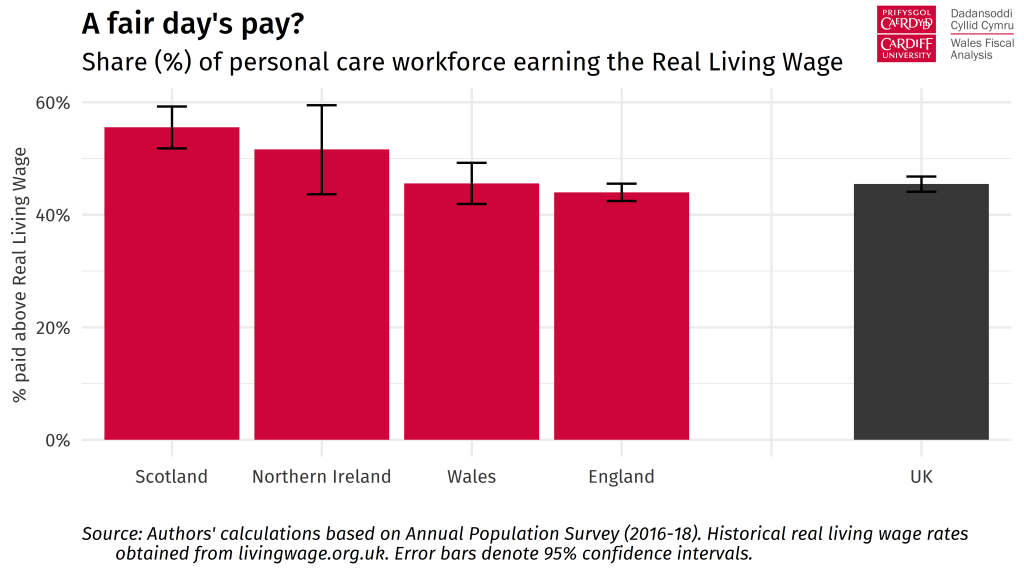

Fewer than half of the personal care workforce in Wales are paid the Real Living Wage. And carers in other parts of the UK do not fare much better. The Real Living Wage – not to be confused with the National Living Wage enshrined in legislation – is currently set at £9.30 an hour (£10.75 an hour in London). By contrast, the median pay for those working in Welsh care homes is only £8.89 an hour.

In light of the current public health crisis, it seems pertinent to ask whether the current level of remuneration for carers is commensurate with the critical role they play in society.

There is certainly room to doubt whether this is currently the case.

Back in May, the Welsh Government announced a one-off £500 bonus payment for staff working in social care settings. The First Minister described this pay award as recognition of an “under-valued and overlooked” workforce. And although there were significant delays in making these payments – which was likely not aided by the composition of the sector, with hundreds of employers and no single pay-determining body – they have started to be paid out this week.

But even once all eligible workers have received their bonus, the one-off nature of the payment means that it will not address the underlying problems associated with low pay in the sector. These were in place long before this crisis began.

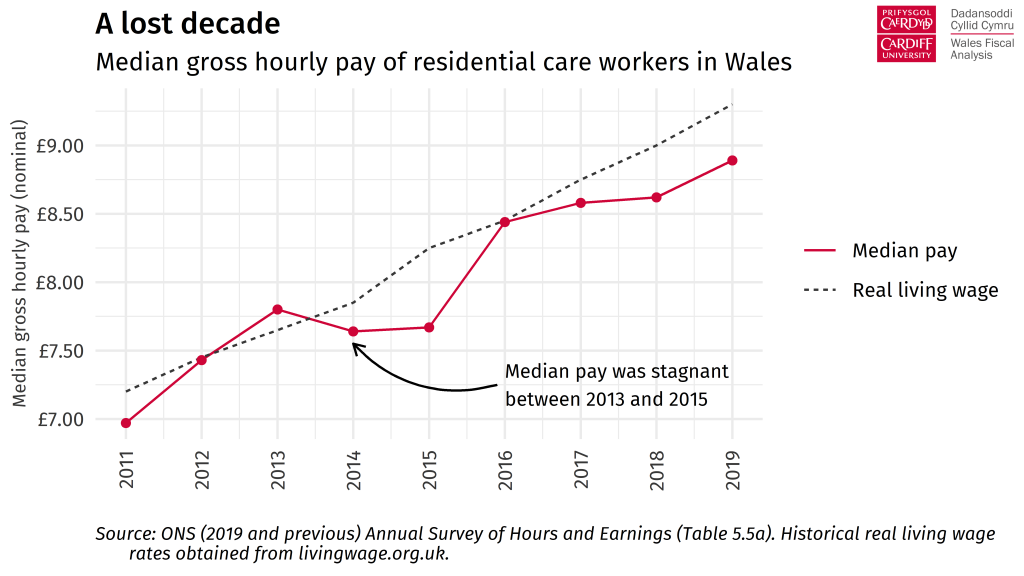

For almost a decade, there has been little improvement in the remuneration of care workers. Having accounted for inflation, median pay has remained stagnant, and has lagged even further behind the Real Living Wages in recent years.

This has, of course, coincided with a period of unprecedently weak earnings growth – particularly in the public sector. Although low earners were exempt from the public sector pay freeze, the median pay for care home workers remained stagnant between 2013 and 2015, which suggests that curbs on public sector pay – even when the lowest paid members of staff are explicitly made exempt – can still have a detrimental impact on wage growth. And this can also have a knock-on effect on wages in the private sector, where most care workers are employed.

This should act as a caution to policy-makers intent on making rash decisions to reign in public spending and introduce controls on public sector pay during the economic recovery.

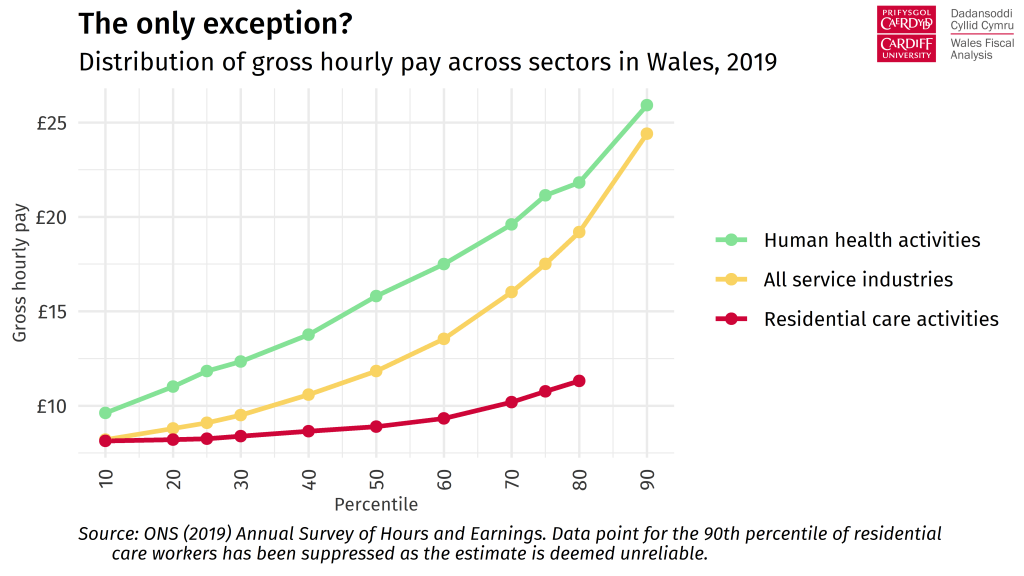

One of the reasons why low-pay in the social care sector is so pernicious is because the issue manifests itself across the earnings distribution. Nearly 70% of workers engaged in residential care activities in Wales are paid less than £10 an hour.

Earnings are substantially lower than for those engaged in human health activities (including NHS workers) across all percentiles. Of course, the higher levels of pay for NHS workers, especially at the higher percentiles, reflects the long periods of training required to be a specialised medical practitioner. But wages in the residential care sector are still much lower than the service industry average across the earnings distribution.

The need to address low pay within the sector is made even more urgent by the fact that it has a decidedly unequal impact. We know that around 80% of care workers are women. And previous research commissioned by the UK Women’s Budget Group suggests that the UK is an outlier in its relative remuneration of care workers compared to other developed countries.

The prevalence of low pay within the sector has its roots in the historical normalisation of caring as unpaid work – by and large performed by women. Even today, the notion of caring as an activity that largely takes place outside the labour market remains embedded in public perception.

In one sense, this closely reflects reality. Informal care provided by friends and relatives continues to be by far the largest source of adult care provision. The cost of purchasing this care at market price is estimated at £8 billion – a similar order of magnitude to the annual NHS budget in Wales.

But the pandemic has arguably created a space in public dialogue to reassess the social value of occupations like social care, and how that squares with the price currently paid for labour. It may yet force a rethink on the value of work performed by unpaid carers as well.

Of course, improving the remuneration of care workers would have substantial resource implications. Given the declining value of central government support to local authorities over the last decade, addressing this issue would require additional funding to be made available by the Welsh Government. This might involve reallocating existing budget lines, or raising additional revenue through devolved taxes.

The pressures of resourcing care for older adults extends beyond the workforce alone – our report takes a closer look at some of these other issues. Needless to say, it seems inevitable that Wales will have to spend more on social care over the next decade. A national conversation about what the future mix of care provision might be, and who should meet this cost is long overdue. Whatever the chosen direction, the remuneration of care workers ought to be a key part of that discussion.

The full report can be downloaded in PDF format here.

- March 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- December 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Reform UK

- Rugby

- Senedd

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections