Autumn Reeves: The 2024 Labour budget and its implications for Wales

31 October 2024

Ed Gareth Poole and Guto Ifan, Wales Fiscal Analysis

Following an election in which both main parties largely ignored the reality facing the UK’s public finances, yesterday’s budget provided something of a fiscal reckoning. It was always likely that public spending and taxes would have to increase – given the state of public services – and the budget delivered an historic increase in the planned size of the UK state.

This blog analyses some of the initial implications for the Welsh Government’s own budget, covering the additional funding through the Barnett formula, the implied choices to be made at December’s Draft Budget, and what the budget tells us about relations between the two Labour administrations.

A big increase in spending on public services

Alongside the spending “black hole” discovered by Labour on taking power, it was always likely that public spending would need to increase relative to the previous government’s implausibly tight spending plans.

To this end, the Chancellor announced £23 billion of additional current spending for 2024-25 and a further large increase in day-to-day spending plans in the following years. Capital spending plans have also been increased by £24 billion by 2028-29, funded through higher government borrowing.

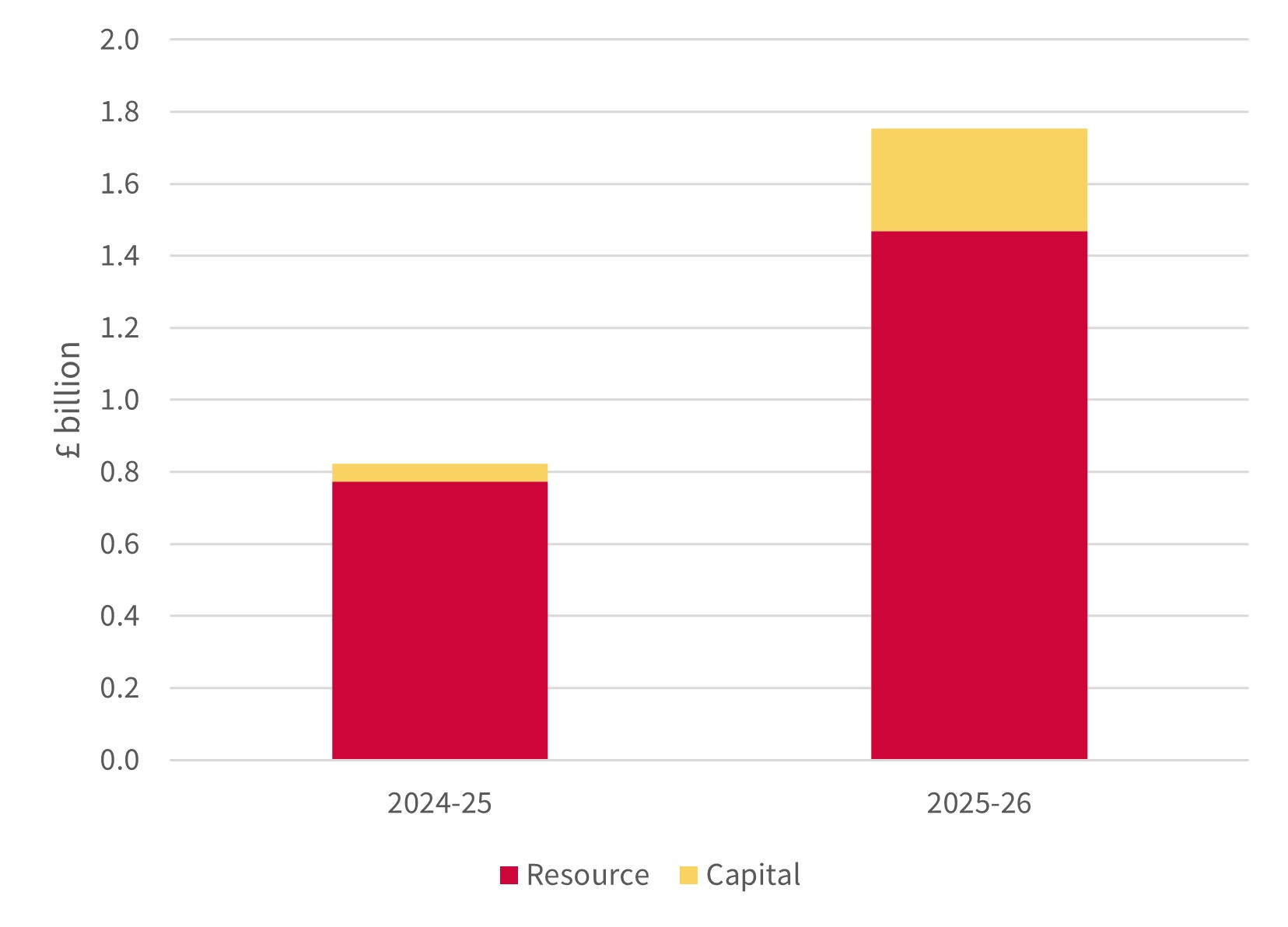

These announcements have a significant impact on the Welsh Government budget (as shown in Figure 1). First, for the current financial year (2024-25), the Welsh Government will receive an additional £774 million for day-to-day spending.[1] This restores the real terms value of the Welsh budget in 2024-25 to what would have been expected at the time of the 2021 Spending Review, when the block grant was originally set and before higher inflation eroded its value.

A large share of this spending will likely go towards the public sector pay deals already agreed for this year. The pay deals of between 4% and 6% across the public sector will likely cost approximately £360 million more than the 2% increases assumed when budgets were first set.

Secondly, the Welsh Government budget increases by a further £930 million in 2025-26 (£694 million of resource funding and £235 million of capital). These announcements have transformed what would have been an exceptionally tricky budget round.

Figure 1: Additional consequentials for Wales (on top of 2024-25 budget)

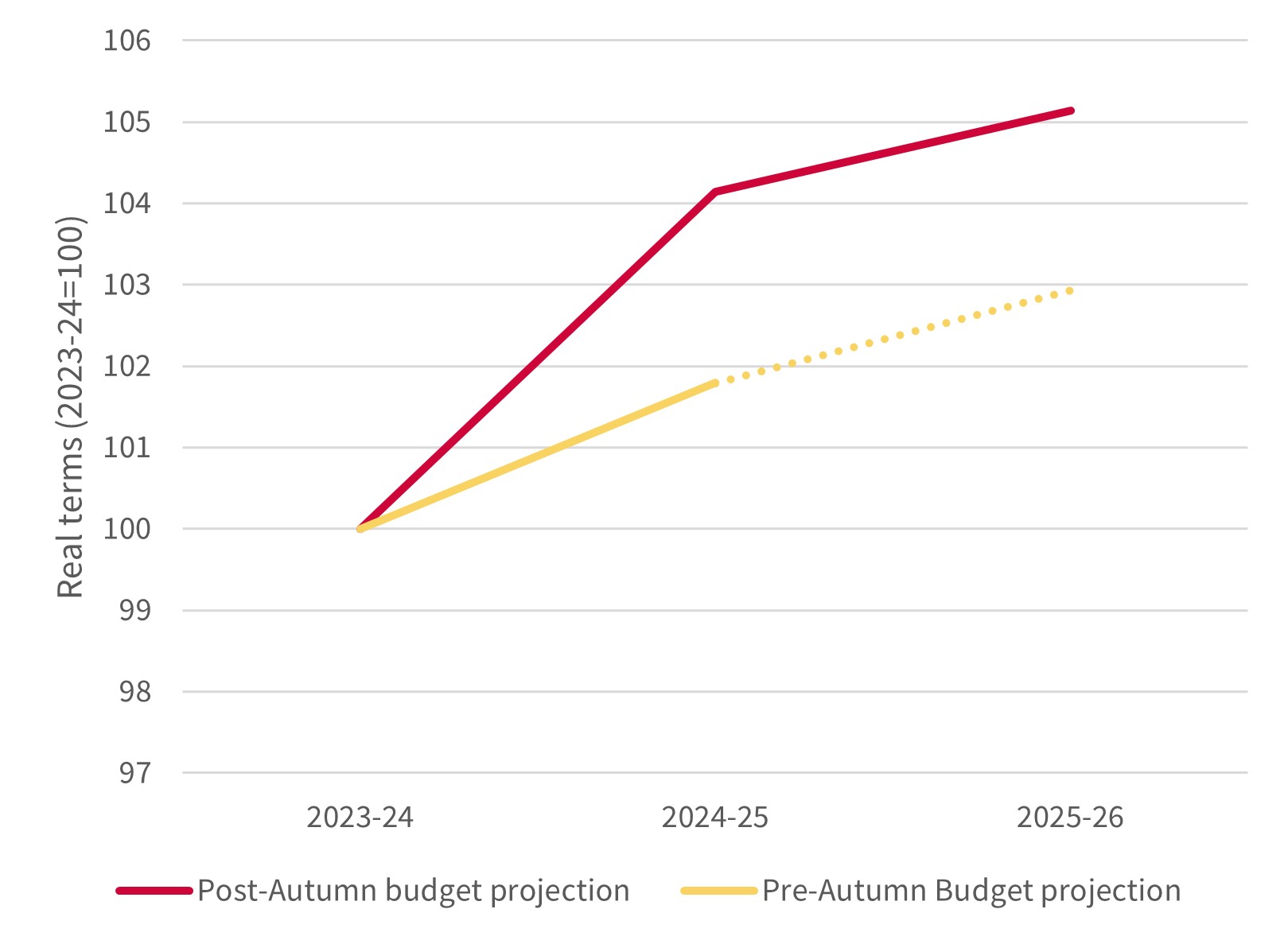

The scale of additional consequentials is remarkable relative to the pre-existing spending plans of the previous Conservative administration, as well as the modest amounts of additional spending promised by the Labour manifesto in the summer. We estimated that Labour’s manifesto implied funding for Welsh Government day-to-day spending would increase by £45 million relative to existing plans in 2025-26. Instead, additional spending in England has boosted resource funding by almost £1 billion relative to those pre-existing plans. As shown in Figure 2, funding for resource spending in 2025-26 will be over 2% higher in real terms than what was expected before this budget.

Figure 2: Real terms trends in Welsh Government resource block grant (before estimated Block Grant Adjustments)

The additional capital spending will also be warmly welcomed by the Welsh Government. During the election, we warned that, under both main parties’ plans, the capital budget would fall in real terms over coming years. Instead, there’s a sizeable increase in the real terms value of the capital budget next year, with some pencilled-in further increases to come. The promise to set capital budgets for five years in future will also provide far greater certainty for the Welsh Government to plan its investments.

Difficult choices remain for the Welsh budget

Despite the dramatically improved budget situation, there are some reasons for caution. Looking across the two years covered by this funding increase, the resource block grant (before Block Grant Adjustments) increases by 2.5% per year on average from 2023-24 to 2025-26. This increase exceeds post-pandemic trends and is far greater than the increases seen during the austerity budgets of the previous decade. However, it falls below the increases seen in block grant during the first decade of devolution, in the context of public services struggling with far greater demand and cost pressures.

The spending increases outlined in this budget are also massively front-loaded. Beyond 2025-26, departmental day-to-day spending growth falls back to a much more modest 1.3% per year, while capital spending starts to fall in real terms by the end of the forecast period. This borrows a trick deployed by previous Conservative chancellors over recent years – increasing spending in the short term at the same time as pencilling-in tighter budget plans in future. Given the perennial real terms increases to the NHS budget, it implies a return to a very difficult medium term outlook for most public services.

In the short term, the Welsh Government will now allocate the additional spending in the current financial year and will publish its Draft Budget for 2025-26 in December. The increase should allow the Welsh Government to provide a substantial boost to NHS spending, while avoiding cuts to most areas of the budget.

A key question, as ever, will be the size of the increase to the NHS budget. The Welsh Government’s Draft Budget for 2024-25 in December topped up NHS spending plans by 8%, with a further £330 million following in the 1st Supplementary Budget in early October. These plans were significantly above planned increases in the other countries of the UK at the time, made possible only because of deep cuts to other areas of the Welsh budget, such as Further and Higher Education, arts & culture, rural investment, and all non-rail transport spending.

Politically, with record high waiting lists and a Senedd election looming, the NHS will once again be front of the queue to receive the additional funding flowing from this budget. Given the context of last year’s Welsh Budget decisions, however, there will be legitimate calls for some of the areas slashed last year to be backfilled instead.

Implications from UK government tax policies

This budget will perhaps mainly be remembered for its historically large tax increases. Alongside the smaller tax increases mentioned in the Labour manifesto, the Chancellor raised a suite of taxes, the most prominent of which was the hike in employer National Insurance Contributions.

As well as allowing further spending on public services, this tax hike will have budgetary implications for the Welsh Government. Some additional UK government funding is yet to be allocated for the direct costs on public sector employers. The Welsh Government will also need to consider the impact on other publicly supported services that fall outside of public sector employment, such as social care, childcare and Welsh universities.

Elsewhere, the Chancellor decided to maintain the temporary Business Rates relief for the hospitality, leisure and retail sector, at a lower 40% rate next year – the level at which the Welsh Government set for this current year. The Welsh Government will need to decide whether to follow suit or remove the temporary reliefs altogether, as the Scottish Government did last year.

There were also increases announced to the higher residential rates of stamp duty (from 3% to 5%) in England and Northern Ireland. As this is a wholly devolved tax, the Welsh Government will consider its own higher rates of the Land Transaction Tax, which are currently set at 4%.

Two strong governments at both ends of the M4?

The additional consequentials deriving from the budget will be warmly welcomed by the Welsh Government. But the Barnett Formula is of course a reflexive tool linked to spending announcements for England. Beyond these automatic adjustments, there is little evidence of Welsh Government influence in Labour’s new corridors of power at Westminster.

The one major Wales-specific announcement was £25 million for coal tip safety – an important commitment for which campaigners have long worked. But given Welsh Government estimates that at least £500m-£600m would be needed over the next 10 to 15 years to prevent future landslips, the scale of the funding is modest in the least.

In fact, other than the HyBont green hydrogen project for Bridgend, Wales was conspicuous in its absence. There was no indication that the Treasury would loosen the Welsh Government’s extremely limited borrowing powers or its ability to carry funds from one year to the next – restrictions which cause extreme uncertainty in budget planning across the entire Welsh public sector.

In the accompanying budget documents, the government announced a much more generous settlement for Northern Ireland: a new 24% needs-based multiplier boost to NI’s Barnett Formula (compared with just 5% for Wales), alongside a £662 million Stormont Executive restoration financial package.

And in what could hardly be more indifferent to the longstanding Welsh rows over “England and Wales” rail infrastructure and HS2 projects, the Chancellor announced a string of electrification and rail infrastructure projects across England – the TransPennine Route Upgrade, Oxford-Cambridge rail, and confirming HS2 tunnelling to Euston – while neglecting to pledge even a platform repaving in Wales.

This further deterioration in Wales’ position on transport funding was revealed in the Statement of Funding Policy, where HS2 and rail infrastructure continued to squeeze the combined Welsh “comparability factor” for transport down from 80.9% in 2015, to 36.6% in 2021, and to 33.5% in 2024. At 95.6% Scotland and Northern Ireland continue to benefit from full Barnett population shares for transport funding that can be used for electrification, opening new lines, or to meet any other spending demand. This is a funding inequity that has long-term consequences yet continues to be ignored at the UK level – despite the change in management.

The Road (or Rail line?) to 2026

This was without doubt an historic budget. The first female Chancellor of the Exchequer, leading for an incoming Labour government, finally dealing with the deep malaise in UK public finances that had been conveniently ignored by both major parties at the general election in July. Huge short-term spending increases, large-scale borrowing and sharp tax hikes shifted the UK closer to European norms on the size of government as a share of the economy.

But with anaemic forecasts for economic growth, business investment and household incomes stagnating, and the OBR projecting very little fiscal ‘headroom’ against the new fiscal rules, governments at either end of the M4 will be hoping that the Chancellor’s investments in public services and public investment bear fruit. If not, the invidious decision on further tax rises or spending cuts will return in less than two short years – just as Welsh Labour face the electorate in 2026.

[1] As outlined in the Welsh Government’s written statement in response to the budget, available here: https://www.gov.wales/written-statement-welsh-government-response-uk-autumn-budget-2024

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- December 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Reform UK

- Rugby

- Senedd

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections