Supporting Neurodivergent Students in Case-Based Learning.

17 March 2024Throughout 2023, I had the pleasure of hearing Rachel Carney, Cardiff University present at several events and workshops. These opportunities opened my eyes to the need to better support neurodivergent individuals within academia. Looking to apply this new knowledge to my teaching practice, and to support others to do the same, I drafted a “support guide” for Case Based Learning (CBL) facilitators. CBL is a student-centered learning approach, used within the medical school during years 1 and 2 of the MBBCh curriculum to promote learning through the application of knowledge to clinical cases and scenarios. I subsequently had the utter pleasure of working with Dr Andreia de Almeida to finesse this draft to create the following which we shared with colleagues 18-03-24 at the start of Neurodiversity Celebration Week 2024.

A guide for CBL facilitators v1.0 2024

Dr Karen Reed & Dr Andreia de Almeida

Neurodiversity describes the idea that everyone experiences and interacts with the world around them in many different ways. Neurodiversity provides a framework for understanding how the human brain functions, arguing that there is diversity in human cognition with no single “correct” way to think.

Neurodiversity is a normal range/variation in the population

Neurodivergent is a term used to describe people whose brains develop or work differently, meaning that they have different strengths and challenges from people whose brains develop or work more “typically”. The latter are often referred to as neurotypical individuals.

Neurodivergent is someone who is dyspraxic, autistic, dyslexic, etc.

Quote: Neurodivergent… means having a mind that functions in ways which diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of “normal”.

Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities book by Nick Walker, p.38

Note: Neurodiverse is often used to refer to neurodivergent groups or individuals. However, a certain group is only neurodiverse if it consists of neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals. A group that is composed only of neurodivergent people will not be neurodiverse. Similarly, one individual cannot be neurodiverse, as diversity relates to various characteristics within a group.

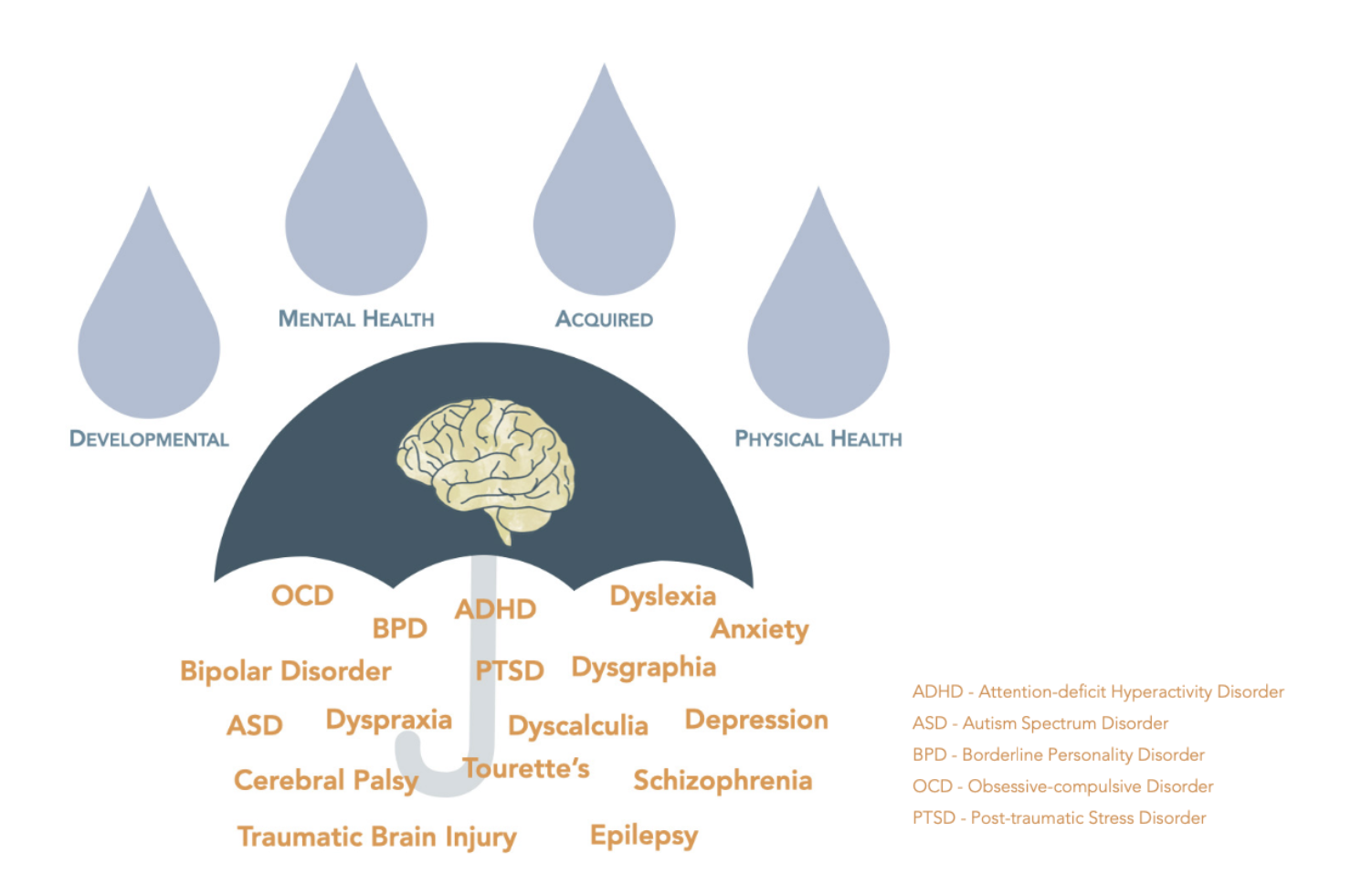

What falls within neurodiversity?

There is a broad range of medical conditions that contribute to neurodivergent traits, including but not limited to ADHD, autism, dyslexia, or dyspraxia (1). However, not everyone will have a diagnosis*, or may not wish to disclose that information with everyone. Therefore, creating an inclusive environment that benefits everyone in the community is important.

Remember, every neurodivergent individual is unique. They are likely to have just as many unique strengths as challenges. This will be different for every person, and as such, it may not be possible to generalise to meet everyone’s needs. An individualised approach is needed.

*While diagnoses are important, it is crucial to remember that, according to the Equality Act 2010, one does not require a formal diagnosis in order to be provided with support. It is also important to note that certain assessments, such as ASD and ADHD, in the U.K., currently have waiting lists that can vary from months to several years (up to 5-7 in certain parts of the country). It is possible for individuals to have a private diagnosis, but this is often very costly, and students might not be able to afford the cost of the diagnosis and medication via a private route.

This schematic is not an extensive list of list of conditions that fall under the “neurodivergent” umbrella term. It was created based on information from various sources, including charities, such as the ADHD Foundation. ADHD Foundation is the charity that founded the “neurodiversity umbrella project” that displays colourful umbrellas across the U.K..

Barriers to Learning

- Inaccessible learning materials:

Learning materials may not be accessible to neurodivergent students.

Examples include textbooks or lecture materials that are not available in accessible formats, videos without captions or screen-reader incompatible online learning platforms. For some, text-heavy learning materials can pose significant barriers to learning.

- Sensory overload:

Neurodivergent students may experience sensory overload in academic spaces. This can be due to loud noises, bright lights, or other environmental factors that can be overwhelming.

- Social isolation and stigma:

These students may feel socially isolated in academic spaces. This can be due to difficulties with social communication or a lack of understanding from peers. This isolation may also stem from stigma and discrimination from peers or faculty/staff.

- Lack of support:

Neurodivergent students may not receive the support they need to succeed in academic spaces. This can include a lack of accommodations, such as extended time on exams or note-taking assistance, or a lack of understanding from faculty and staff.

What can you do as a facilitator?

Follow the principles that are encompassed by the ideology of a universal design for learning (UDL) approach (2).

- Create an inclusive learning environment:

Ask group members what they need/don’t need to support effective learning. By conducting a sensory audit of the group (asking students what does and doesn’t work for them), you will be able to consider adapting the learning environment to cater to the unique needs of the group members, including neurodivergent individuals. For example, reducing visual or auditory distractions, normalising space for relaxing, and/or sensory deprivation (stepping out of the room for a few minutes) can help.

- Remember that everyone is different

Neurodivergent students may have different learning styles and may not learn in a linear and stepwise manner. Creating environments that optimise flexible learning approaches can help cater to individuals’ unique needs.

- Acknowledge the notion of academic ableism

Academic ableism describes the discrimination of disabled people in academic spaces. The educational system has many barriers for neurodivergent students, which are often invisible and unrecognised. Some examples are provided below, but recognizing the notion of academic ableism can help create a more inclusive learning environment for all students.

- Make things simple and structured:

Nobody likes things to be unnecessarily complicated, but remember, neurodivergent students may have particular difficulty understanding complex instructions. Therefore, it is important to provide clear and concise instructions that are easy to follow. Similarly, a structured learning environment can help neurodivergent students stay organized and focused. This can include providing a clear schedule, breaking down tasks into smaller steps, and using visual aids. Offering plenty of opportunities for personalised compassionate feedback (two-way feedback is best) can really help. The best practice is to work with individuals to meet their specific needs and build on their strengths.

- Be conscious of your communication

Everyone needs to be cognisant of the impact of unconscious biases and stereotypes, particularly when communicating with others. A lack of consideration can unwittingly result in signals that are counterproductive to providing an inclusive learning environment, e.g. annoyance at students being fidgety (see academic ableism above). If not appropriately considered, miscommunications can easily add to the burden of microaggressions that neurodivergent students are frequently exposed to.

Quote: Allowing a student with a hidden disability (ADHD, Anxiety, Dyslexia) to struggle academically or socially when all that is needed for success are appropriate accommodations and explicit instruction is no different than failing to provide a ramp for a person in a wheelchair.

Joe Becigneul, board chair at the Greater St. Albert Catholic Schools in Alberta, Canada

Content inspired by workshops provided by Rachel Carney, Cardiff University.

Providing Feedback on this resource

We appreciate any feedback, comments and suggestions on this resource. For any queries, please contact: Dr Karen Reed (reedkr@cardiff.ac.uk) or Dr Andreia de Almeida (deAlmeidaA@cardiff.ac.uk)

References

1 – NHS England (2022) A Guide to Practice-Based Learning (PBL) for Neurodivergent Students

2 – La, H., Dyjur, P., & Bair, H. (2018). Universal design for learning in higher education. Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning. Calgary: University of Calgary

Further reading and other resources

Blog – THE, How can we create accessible and inclusive learning environments for neurodivergent students?

Blog – Faculty Focus, Bridging the Gap: Overcoming Barriers in Higher Ed for Students with Disabilities including Neurodivergent Learners

Blog – Cardiff University, Diversity in STEM – Understanding the needs of neurodivergent students, including recording of online event.

Network – Cardiff University Neurodiversity and Inclusivity Staff Network

Journal Article – Hamilton, L. G. and Petty, S. (2023) Compassionate pedagogy for neurodiversity in higher education: A conceptual analysis, Frontiers in Psychology

Book – Brown, N (Ed) 2021. Lived Experiences of Ableism in Academia. Strategies for Inclusion in Higher Education Policy Press ISBN: 978-1447354116

- Diabetes & Menopause: What Everyone Should Know (and Why Oestrogen Matters)

- Personal Reflection: Initiating and Organising “Menopause in Focus” at Cardiff University

- Supporting introverted medical students.

- From Maternity Leave to EDI Lead: A Journey I Never Planned

- Resilience is a measure of privileged