Diabetes & Menopause: What Everyone Should Know (and Why Oestrogen Matters)

7 December 2025

It is Sunday 7th December as I write this, and given that last week, and next week, that is the last 2 weeks of teaching of 2025, I have been supporting Year 2 MBBCh students who are studying a diabetes case featuring a woman in her 60’s, I had wanted to share a resource that explores the link between diabetes and menopause. However, time has run away from me, so the best I can do is a blog post on the topic. To see this come to fruition, rather than it remain as an unfinished item on the wish list in my head, I have used both the Elicit tool and Copilot, made available to me by Cardiff Uni, to help draft this text (and draw the image). My aim is to provide a scientifically sound overview, with references to peer-reviewed research (which I confess I have not read with my usual vigour and critique), that connects what students are learning to real-world physiology and clinical implications. Feedback and comments are welcomed, if constructive and polite.

So why does menopause matter for diabetes risk?

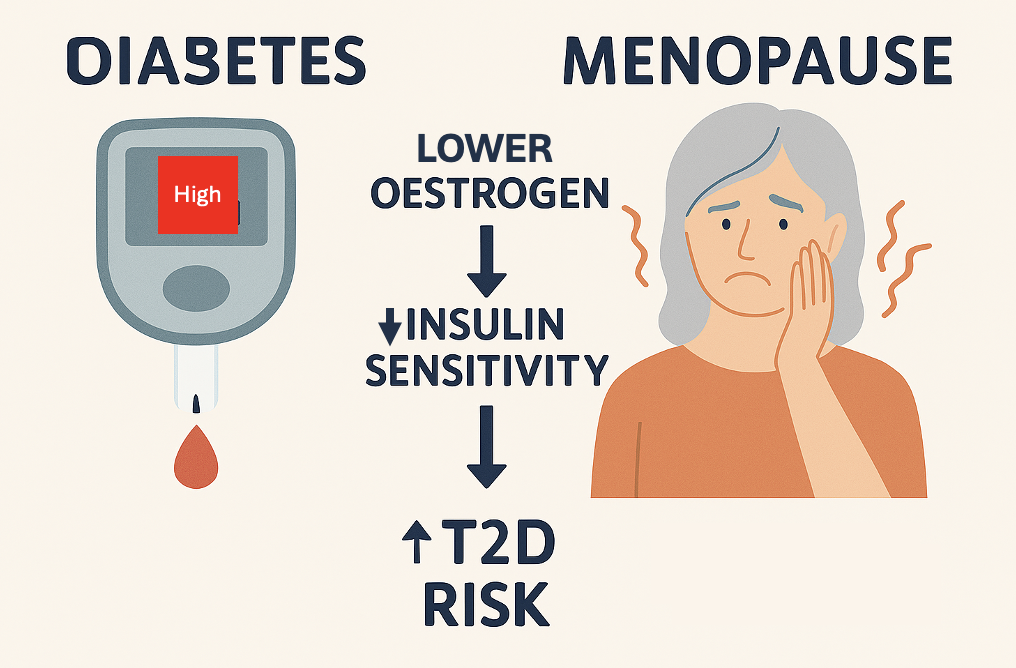

Menopause isn’t only about hot flushes and sleep disruption; it’s a metabolic turning point for many of us. One big question that I think it is important to ask is: does the drop in oestrogen change insulin sensitivity and raise the risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D)? The short answer appears to be YES.

Oestrogen is a key regulator of insulin action, and falling levels of oestrogen around menopause can tilt metabolism toward insulin resistance.

The longer answer (with the accompanying evidence) is below.

The link between oestrogen and insulin.

Oestrogen, especially 17β‑oestradiol (E2), supports how our bodies handle glucose. It does this through multiple receptors (ERα, ERβ and G‑protein‑coupled estrogen receptor, GPER), influencing pancreatic β‑cell function, glucose transporters such as GLUT4, hepatic glucose production, adipose tissue distribution, and inflammatory pathways that drive insulin resistance. In preclinical and translational work, oestrogen signalling via the ERα/PI3K/Akt pthway suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis and improves insulin sensitivity, which helps keep fasting glucose down (Meyer et al., 2011; Prossnitz & Barton, 2011; Yan et al., 2019).

As oestrogen levels decline during the menopause transition, insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance can worsen, increasing T2D risk beyond what we’d expect from ageing alone. Clinical reviews conclude that menopause is accompanied by central fat redistribution, reduced energy expenditure, and impairments in insulin secretion and sensitivity—a combination that predisposes to T2D (Lambrinoudaki et al., 2022; Paschou et al., 2019).

Is it “proven” that oestrogen alters insulin sensitivity?

YES! Both mechanistic and clinical evidence support this. Experimental studies show E2 improves insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism; blocking or losing oestrogen signalling pushes the system the other way (Yan et al., 2019).

Clinically, the most rigorous measure of insulin action (the hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp) demonstrates a timing effect between estradiol administration after menopause and the effect on insulin action: short‑term transdermal oestradiol increased insulin‑mediated glucose disposal in women ≤6 years post‑menopause but decreased it in women ≥10 years post‑menopause. This “timing hypothesis” suggests oestrogen’s metabolic benefits are more likely when therapy is initiated closer to menopause, and may be blunted or reversed later (Pereira et al., 2015).

At a population level, large, randomised trials and meta‑analyses show that menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) reduces the incidence of Type 2 diabetes and improves glycaemic indices—yet it’s not licensed solely to prevent diabetes because benefits must be weighed against individual risks (Mauvais‑Jarvis et al., 2017; Speksnijder et al., 2023).

The take home messages from reviews of the trials.

- Randomised trial evidence & systematic reviews: Multiple RCTs (including Women’s Health Initiative sub‑analyses) and synthesis papers report lower diabetes incidence in women assigned to oestrogen‑based MHT versus placebo, with improvements in insulin sensitivity and β‑cell function (Mauvais‑Jarvis et al., 2017).

- Glycaemic control in women with diabetes: A 2023 meta‑analysis of 19 RCTs found that postmenopausal HT reduced HbA1c (~0.56%) and fasting glucose (~1.15 mmol/L) in women with diabetes, indicating neutral‑to‑beneficial effects on glucose regulation when therapy is used for symptoms (Speksnijder et al., 2023).

- Insulin resistance in healthy postmenopausal women: Newer data (2024 meta‑analysis of 17 RCTs) presented at The Menopause Society reported significant reductions in insulin resistance with both oral and transdermal oestrogen, with a stronger effect for oestrogen alone compared to oestrogen plus progesterone.

- Safety and individualisation: Contemporary clinical guidance emphasises individual risk stratification (especially cardiovascular/thromboembolic risk), route (oral vs transdermal), and timing (preferably within 10 years of menopause), rather than blanket recommendations (Paschou et al., 2024).

So, does menopause itself cause insulin resistance and T2D?

It seems this is very nuanced. Many longitudinal and cross‑sectional datasets link menopause to rising central adiposity and metabolic changes that raise T2D risk. However, when insulin sensitivity is measured using the hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp methodology, differences between pre‑ and post‑menopausal women can be modest after adjusting for age and adiposity. Overall most evidence still favours a metabolic impact of oestrogen loss, especially via changes in fat distribution, hepatic glucose output, and inflammatory tone, that increases T2D risk in some women (Lambrinoudaki et al., 2022: Lovre & Mauvais‑Jarvis, 2025).

Emerging cohort data also suggest the risk profile isn’t static across the menopause transition: insulin sensitivity often declines first, with β‑cell function dropping later as diabetes approaches, underscoring the importance of early lifestyle and clinical interventions (Choi & Yu, 2025).

Where does GPER fit in?

Beyond ERα/ERβ, GPER (a membrane oestrogen receptor) appears to modulate body weight, inflammation, and glucose and lipid homeostasis. Animal models lacking GPER show greater adiposity and insulin resistance, while pharmacologic activation of GPER can improve metabolic outcomes. This points to additional receptor pathways through which oestrogen influences insulin sensitivity (Sharma & Prossnitz, 2017: Prossnitz & Barton, 2011).

Practical steps to protect metabolic health in midlife

- Know your numbers: Track fasting glucose, HbA1c, blood pressure, lipids, and waist circumference—changes in central fat are particularly relevant in menopause (Lambrinoudaki et al., 2022).

- Protein + resistance training: Preserve and build lean muscle (a major sink for glucose). Aim for 2–3 sessions/week (Lambrinoudaki et al., 2022).

- Fibre and high‑quality carbs: Emphasise minimally processed foods and soluble fibre to steady post‑meal glucose.

- Sleep & stress: Poor sleep and stress hormones (cortisol) nudge glucose upward; prioritise sleep hygiene and stress management.

- Speak with your healthcare provider: If you have menopausal symptoms, discuss MHT in the context of your personal cardiovascular and metabolic risk profile (Paschou et al., 2024).

Bottom line

- Oestrogen influences insulin sensitivity, and the fall in oestrogen at menopause can predispose to insulin resistance and T2D through receptor‑mediated effects on liver, muscle, adipose tissue, and pancreatic β‑cells (Yan et al., 2019)(Lambrinoudaki et al., 2022).

- MHT can improve glucose metabolism and lower diabetes incidence, particularly when started closer to menopause, but it’s not recommended solely to prevent T2D; decisions should be individualised (Mauvais‑Jarvis et al., 2017)(Pereira et al., 2015).

- Lifestyle remains foundational. If you’re noticing fluctuating glucose or new abdominal weight gain, it’s not “just you”—these are well‑described changes in menopause, and we have tools to address them (Lambrinoudaki et al., 2022).

References

- Diabetes & Menopause: What Everyone Should Know (and Why Oestrogen Matters)

- Personal Reflection: Initiating and Organising “Menopause in Focus” at Cardiff University

- Supporting introverted medical students.

- From Maternity Leave to EDI Lead: A Journey I Never Planned

- Resilience is a measure of privileged