Two Czechoslovakias

18 November 2024Liz Kohn is an MPhil student working with Prof Mary Heimann and Dr Tetyana Pavlush on ‘Invisible Women in the Slánský Trial‘. In her blog, she explores two different sides of Czechoslovakia – one consigned to history, the other recreated through memory and the imagination.

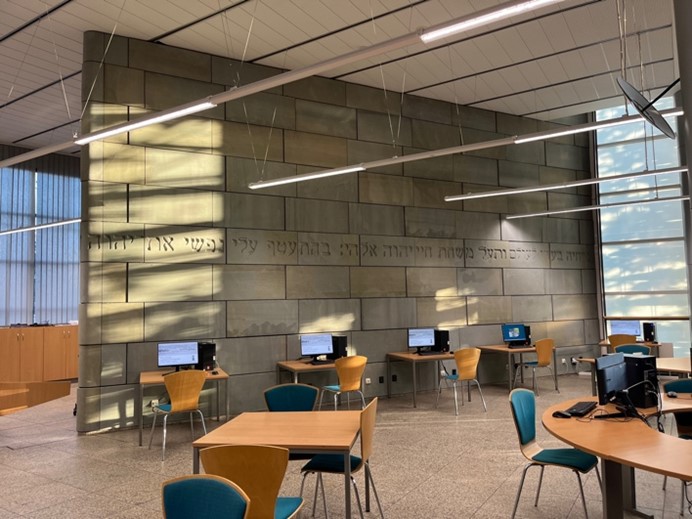

Liberec, a city in Northern Bohemia, boasts a stunning new library. Its huge atrium is filled with light from the enormous plate-glass walls. There is a welcome desk and a café at the entrance and a wide, open-tread staircase leading up to the library itself. Protruding into the vast entrance hall is a triangular wedge of dark grey stone walls, engraved with Hebrew lettering. The library has been built on the site of Liberec synagogue that was blown up in 1938 when the Germans occupied the Sudetenland.

The two grey walls are part of a small modern synagogue accessed from beside the library entrance. The first time we tried to visit, it was locked. The sign on the door said it was open from 9-12 every week-day morning. We returned one morning; it was still locked. I went to the library information desk and asked about it and whether it would be opened. I was told the synagogue was nothing to do with the library. Yet it was. Surely the architect had intended the presence of the synagogue to be a constant reminder to the citizens of Liberec. The site of their new library had originally belonged to the Jewish community. Why design two huge jutting walls into the very centre of the library, if not as a reminder of that?

Yet it seems that it is easy for the present citizens of Liberec to overlook these reminders.

I was in the Czech Republic, travelling beyond Prague to get to know more of the country and the countryside, but also to visit places connected to the story of Alice and of my father. Each time I go, I am closer to and further away from touching the world they inhabited – Czechoslovakia. That country is no more. It exists only as a historical fact, a state that was formed in 1918 and dissolved in 1992, when Czechia and Slovakia became two countries. Present day Czechs and Slovaks do not think of themselves as Czechoslovaks and if someone in Czechia asks me why I speak Czech and I say my father came from Žilina, their response is, “Oh, he was Slovak.” No, he wasn’t, he was Czechoslovak.

Czechoslovakia may have been consigned to the past by the Czechs and Slovaks who live in that former country, but some of us are still searching for it. We do not inhabit or belong to the new reality. In the memories of those who were forced to leave and in the imagination of those who were never there, yet are still connected through family and history, Czechoslovakia lives on. Linking across the globe from Canada and the US to Britain and Poland, Israel and Switzerland, the descendants of those who left are repairing ruptured links and revisiting the world that was lost. We are gathering the threads of memory and evidence to weave into a tapestry of the past, seeking to recreate the world we never knew.

This was brought home to me while I was there, when I received two emails from strangers within days of each other. The first was from the son of Vojtech Schlesinger, the lawyer in whose office Alice worked when she first moved to Žilina with Erwin and, I discovered, was the owner of the apartment and consulting rooms that they rented. The second was from the daughter of someone who had been in Auschwitz with Dora, Alice’s friend and co-defendant. This has happened so many times now, that emails from strangers reveal the connections between us, the close links and friendships of our parents. We are so pleased to have yet another strand to add to our ever-expanding understanding of the world they had inhabited in that small country which they had loved and been forced to leave.

When we visit the lands that once were part of Czechoslovakia, we search for what was lost, the buildings where our parents lived, worked, studied. Some remain, some have sunk into disrepair, others have been transformed or replaced. The new Liberec library with its small synagogue intruding into the atrium seems to be an effort to reconcile past and present. But so much of the past is absent. A few stumbling stones (stolpersteine) can be found, little brass squares with the names of those who emigrated or were killed, and I always stop and read them. They were not my relatives, but I hope somewhere some descendants of those lost families are forging new lives.

There are four stolpersteine outside Villa Tugendhat, which we visited in Brno. The stunning villa designed by Mies van de Rohe is now a tourist attraction, but the family for whom it was built, fled from the Nazis. I was expecting the guide to explain a little about the persecution Jewish families faced, but it was hardly mentioned, just in passing that they had emigrated because of the Nazi Protectorate. I thought too the guide might mention that the family’s textile factory was the one Schindler had used to save 1,200 Jews. But, no. There was an exhibition of pictures about the Schindler factory, but it was not drawn to our attention.

Later in the trip, we decided to try and find the Schindler factory, that had belonged to the Low-Beer family, for whose daughter Villa Tugendhat had been built. It was not easy to find, but eventually, having asked several people in the small town of Brnenec, we found it, deserted and almost derelict. It was a wet and cold day which intensified our sense of the desperate history that had been played out there. The real Czech Republic still bears the scars of its history, but those who live there today are just getting on with their lives, the past is in the past. For those, like me, who are searching for signs of that past, there are two countries, the one I am visiting as a tourist and the one in my imagination that I am trying to envisage and understand.

Many of those living in Czechia and Slovakia have their own tortured pasts, but they have survived into the new reality. Their focus is on the lives they lead now, and the younger generation can hardly remember the hardships of the Communist past. Only the very old remember the war, it is history, but history is written by people, and they choose which history to tell. Visiting the Modern Art Museum in the Veletržní palác, I was once again struck by what was absent. So many of the artists and patrons of the arts had been Jewish. Their possessions, including their art works, were confiscated. Why was this never mentioned? Why, when discussing the ‘the period’s multi-layered and internally conflicted art scene’ is there no mention of the ethnic and national diversity within Czechoslovakia? And why, in the epilogue to the exhibition, was the fact that, ‘Czechoslovakia sheltered approximately 10,000 officially registered refugees from Germany and Austria’, many of whom were artists, writers and intellectuals, foregrounded, yet there was no mention of the thousands of Jews deported and murdered from Czechoslovakia later in the war? I find myself searching for a recognition of the contribution our ancestors made to what was Czechoslovakia.

There are memorials, most recently the naming of a street in Prague after Nicholas Winton, but they are gestures. The history of the Jews of Czechoslovakia is not integrated into the history of Czechoslovakia, it is somehow separate, still in a metaphorical ghetto. It is in a locked synagogue that juts into Liberec library but that the citizens of Liberec ignore.

It seems that there are two Czechoslovakias, one consigned to history, the other being recreated fragment by fragment through the memories and imagination of the descendants of those forced to leave. I was going to distinguish between the two as one real and the other metaphorical, but in a way, neither ever existed in the material world. Nation is a concept and there are at least two concepts of Czechoslovakia, one which includes the Jews and one which ignores them.

Quotations are from the displays in the Modern Art Museum in the Veletržní palác.

Alice Glasner a.ka. Glasnerová (1905-1986) was a Czechoslovak lawyer and a Communist Party member. She volunteered in the Spanish Civil War and worked for the International Workers Order in New York during the Second World War. After the war she returned to Czechoslovakia and was imprisoned as part of the Slánský trial. She was my father’s first wife and I have been researching her life since 2015 and writing a regular blog about my research (https://lookingforalice.com).

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’

- Collaboration across the pond: uniting histories of religious toleration in the American Revolution and European Enlightenment