Pétain’s Silence

27 October 2025In his blog post, Professor Kevin Passmore draws on his new third-year module on Occupied France and on his experience as a former Registered Mental Nurse to explore Pétain and his silence.

As constituted, the High Court does not represent the French people. Consequently, the Marshal of France, Head of State, will address the people alone. I will make no other statement. I will answer no questions. I have entrusted my lawyers with the mission of responding to accusations that are intended to tarnish me, but which only tarnish the accusers.

These were the words of 89-year-old Marshal Philippe Pétain, chief of the dictatorial and collaborationist Vichy regime that governed France during the German occupation of 1940–45. He spoke them on the first day of his trial for ‘collusion with the enemy and endangering the internal security of the state’. Aside from the odd outburst, he sat silently through weeks of witness testimonies, sometimes dozing, occasionally agitated and flustered. On 15 August, the jury found him guilty, but recommended that, on account of his advanced years, the death sentence should not be carried out.[1]

The ostensible reason for Pétain’s silence was that as the legal head of state – a pretension dismissed by the Provisional Government of the restored Republic – he could only be tried by the Senate. The unspoken suspicion was that Pétain’s mental deterioration – an open secret – was too severe for him to respond coherently to cross questioning. Yet silence had marked Pétain’s entire life and being. Understanding it historically requires bringing legal, cultural and political history together with psychology and psychiatry.

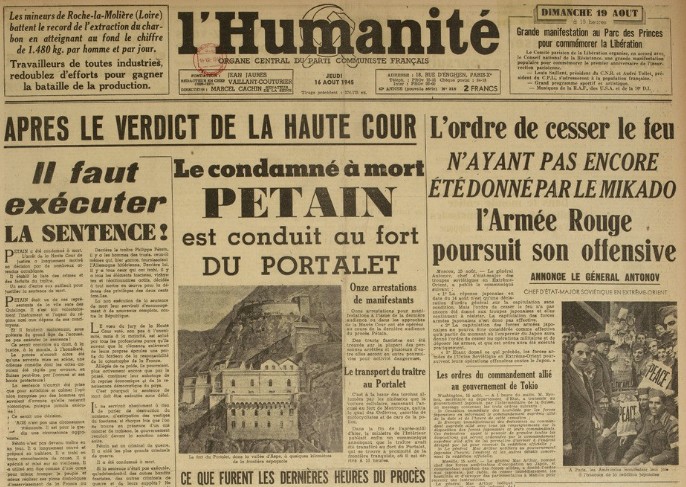

Legally, there was no chance that the court would consider Pétain unfit to stand trial, for there was no such possibility in French law. Quietly shelving prosecution was also impossible because the Provisional Government and public opinion demanded the punishment of collaborators. The Resistance press dismissed Pétain’s memory lapses and deafness as manipulation. The communist Humanité saw an old trickster, who ‘sometimes plays senile and deaf and sometimes demonstrates astonishing memory and extraordinary lucidity’.[2]

Pétain’s senior lawyer, Maître Fernand Payen, wanted to plead article 64 of the Penal Code: ‘There is no crime or offense if the defendant was in a state of insanity at the time of the act’. This defence was challenging: since the prosecution intended to show that Pétain had plotted since the 1930s to overthrow the Third Republic (1870-1940), it would be necessary to show ‘insanity’ dating back years. In 1945, defence counsel would not have thought of arguing that Pétain had long suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. Although this illness had been identified in the 1900s, it was thought to affect only young people, while senility was considered to be simply a possible consequence of old age and not the province of psychiatry. In any case, Pétain himself saw such a plea as humiliating. In French, pleading senility is known colloquially as ‘plaider gâteux’, and the adjective ‘gâteux’ derives etymologically from the verb ‘se souiller’, to soil oneself. Furthermore, the old marshal had returned voluntarily to France from exile in Switzerland to ‘defend his honour’ before the courts. During the proceedings, Payen’s euphemistic references to Pétain’s ‘tiredness’ and ‘vulnerability to manipulation’ visibly annoyed him.

The Marshal preferred the strategy of his younger counsel, Maître Jacques Isorni, who pleaded that apparent treason was in fact the clever and rational pursuit of a policy of lesser evil, which saved France from the fate of occupied Poland. This defence required Pétain’s silence, for his confusion, of which Isorni was well aware, might under questioning contradict the depiction of him as a highly skilled negotiator. During the trial, Isorni established his own status as a great lawyer and laid the foundations of what became the standard defence of Pétain, which his shrinking band of supporters maintain to this day. Understandably, academic historians have been more concerned with refuting this exculpatory myth than with the possibility that Pétain’s dementia was historically significant.

In 2019, two geriatricians provoked a minor media storm when they suggested that Pétain suffered from Alzheimer’s Disease, possibly complicated by vascular episodes.[3] They pointed to memory lapses, difficulty in assimilating new information, indecisiveness, apathy, tiredness, tendency to digression and an obsessive conviction that the head of the Provisional Government, General Charles de Gaulle, planned to free him. They could have added his liking for joining children’s games. The geriatricians recognized the absence of symptoms such as balance issues, hallucination and delusion.[4] Yet dementia covers multiple pathologies, manifesting in various ways. A contemporary doctor would probably also have suspected cognitive decline due to advanced syphilis, for the younger Pétain had been notoriously promiscuous; the disease was rife in the officer corps and secondary syphilis was then a major cause of confinement in psychiatric facilities. Retrospective diagnosis is intrinsically problematic, especially in cases such as this, which require physical tests. Yet there is ample evidence that Pétain suffered from mental impairment, whatever the precise aetiology.

His symptoms were plain during the war. However, cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s may begin ten to fifteen years before diagnosis. Mental difficulties due to syphilis would have appeared ten to thirty years after infection. In Pétain’s case, the first reports of problems dated back to 1922, when he was head of the army. The Chief of General Staff, General Edmond Buat, told his diary that ‘while at certain moments [Pétain’s] ideas remain clear, at others, everything is muddled and hard to follow’.[5] In the following years, Pétain frequently refused to decide, reversed his position, and obsessively repeated ideas that were not easily challenged, such as his dislike of school teachers. Dementia sufferers often use entrenched moral positions to disguise impairment, however inappropriate they are in particular situations, which they struggle to understand. Of course, in the absence of a patient, we cannot be certain about Pétain’s mental state.

We can be still less sure because Pétain had never been loquacious. He did not speak until the age of three, perhaps because he had been traumatised by the early loss of his mother and the indifference of his step-family. He was never comfortable in one-to-one encounters, and, as a senior officer, he was not used to being questioned. His most recent biographer, Bénédicte Vergez-Chaignon, shows that as Pétain’s popularity spread during the Great War, he deliberately used a strategy of ‘rare and precious speech’. Rarity compensated for social awkwardness yet gave his public utterances special importance, thus sustaining the illusion that he represented the nation as a whole, while confining his anti-republican utterances to the private sphere.[6] In 1945, the Resistance press was right that Pétain’s silence was a calculated defence strategy. Moreover, he had honed his use of silence over many years. Yet it is impossible to disentangle political calculation from compensation for cognitive impairment. It is nevertheless legitimate to say that In 1945, Pétain was not entirely unaware of his circumstances, even if he could not understand them. He was certainly impenitent.

For historians, the point is not to judge, still less excuse Pétain. In a democracy, penal responsibility is a question for the law and for courts advised by experts. Historians are interested in the reasons for his silence, its meaning and its consequences.

Silence had made Pétain strong and weak. Strong because it sustained the immense popularity that enabled him to be seen as a saviour amidst defeat in June 1940. Weak because it encouraged others to attempt to annexe his popularity for their own ends – Isorni was only the latest to do so. Weak also because maintaining popularity made him reluctant to decide and ready to compromise with the Nazis’ plan for the racial restructuring of Europe.

[1] For the trial see Julian Jackson, France on Trial (2023).

[2] ‘Pour gagner du temps Pétain-Bazaine fait appel aux témoignages d’outre-Atlantique’, L’Humanité, 26 May 1945.

[3] Jadwiga Attier-Zmudka and Jean-Marie Sérot, ‘A Particularly Tragic Case of Possible Alzheimer’s Disease, that of Marshal Pétain’, Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 71 (2019), pp. 399–404.

[4] A delusion derives from an abnormal process, such as ‘the green blanket on my bed proves that de Gaulle plans to free me’.

[5] Journal du général Edmond Buat : 1914-1923, ed. Frédéric Guelton (2015), 16 January 1922.

[6] Bénédicte Vergez-Chaignon, Pétain (2014), pp. 132–3, 211–12.

Further reading

AJ Larner, ‘Retrospective diagnosis: Pitfalls and purposes’, Journal of Medical Biography 27:3, (2019), pp. 127-128.

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- How Troubled Was My Valley? 1941’s How Green Was My Valley and Contemporary America

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’