Perishables: Encounters with the Ephemeral in the early East India Company Archive

28 May 2024In this blog, Mark Williams reflects on what a chance encounter with 350-year old pieces of cloth in an archive might tell us about the history of the English East India Company, material encounters with the past, and those histories that elude us

Every historian can point to a moment in the archive that prompted a sharp intake of breath: fleeting moments and chance encounters with traces of the past they never expected – or indeed, never hoped – to have. The ‘archive’ may mean any number of things in this sort of context: collections of manuscripts in vast libraries, but also letters and objects in private homes, material remains in museums, or oral testimonies recorded on a range of mediums. Wherever that archive might be, the past has a habit of suddenly making itself known to us suddenly, unexpectedly, and in forms we never thought we’d find.

For me, such a moment arose while reading through the surviving papers of an East India Company merchant named Nicholas Buckeridge. The English East India Company (EIC) which employed Buckeridge had been founded at the turn of the seventeenth century by royal charter to trade into the ‘East Indies’ – a term which at that time referred primarily to present-day Indonesia and its ‘Spice Islands’. Whether through diplomacy or, more often, by gunpoint, European traders hoped to extract fashionable and profitable spices such as nutmeg, mace, cinnamon, and pepper. English competition for this trade was driven both by the need to circumvent the control of eastward trade by the Ottoman Empire and to wrest some of the profit away from the Portuguese and Dutch empires. As English competition for dominance of this trade encountered opposition – both from other Europeans and indigenous powerholders across Asia – new routes to profit were sought out in present-day India, Thailand, Japan, Persia, and East Africa. What unfolded in the centuries that followed saw phases of both amicable and violent encounter, exploitation, the accumulation of vast wealth as well as instances of profound failure for all parties.

Nicholas Buckeridge’s life was one among thousands caught up in this emergent global trade. Unlike many EIC merchants, we know a fair amount of his origins. While his date of birth is unknown, he was from a branch of the Buckeridge family that had seen one of his uncles – John Buckeridge – elevated to the bishopric of Ely, and a founder of St John’s College at Oxford University. Nicholas was one of seven sons, and as such likely entered Company service to seek a fortune which would not be wholly dependent on family patrimony. He was not the only Buckeridge son to become a merchant: his brother, Edward, was also a well-established London merchant at the same time. Whatever Nicholas’s motives, he enters into Company correspondence in the early 1640s as Britain and Ireland descended into civil war, assisting in a voyage to Basra in present-day Iraq. In the coming years and decades, he would variously find himself travelling to Mocha, Aden, Bandar Abbas, Mozambique, Surat, Madras (Chennai), and many others before finally retiring in the 1670s. Unlike many of his Company contemporaries, he would die peacefully in England, either in 1688 or 1689.

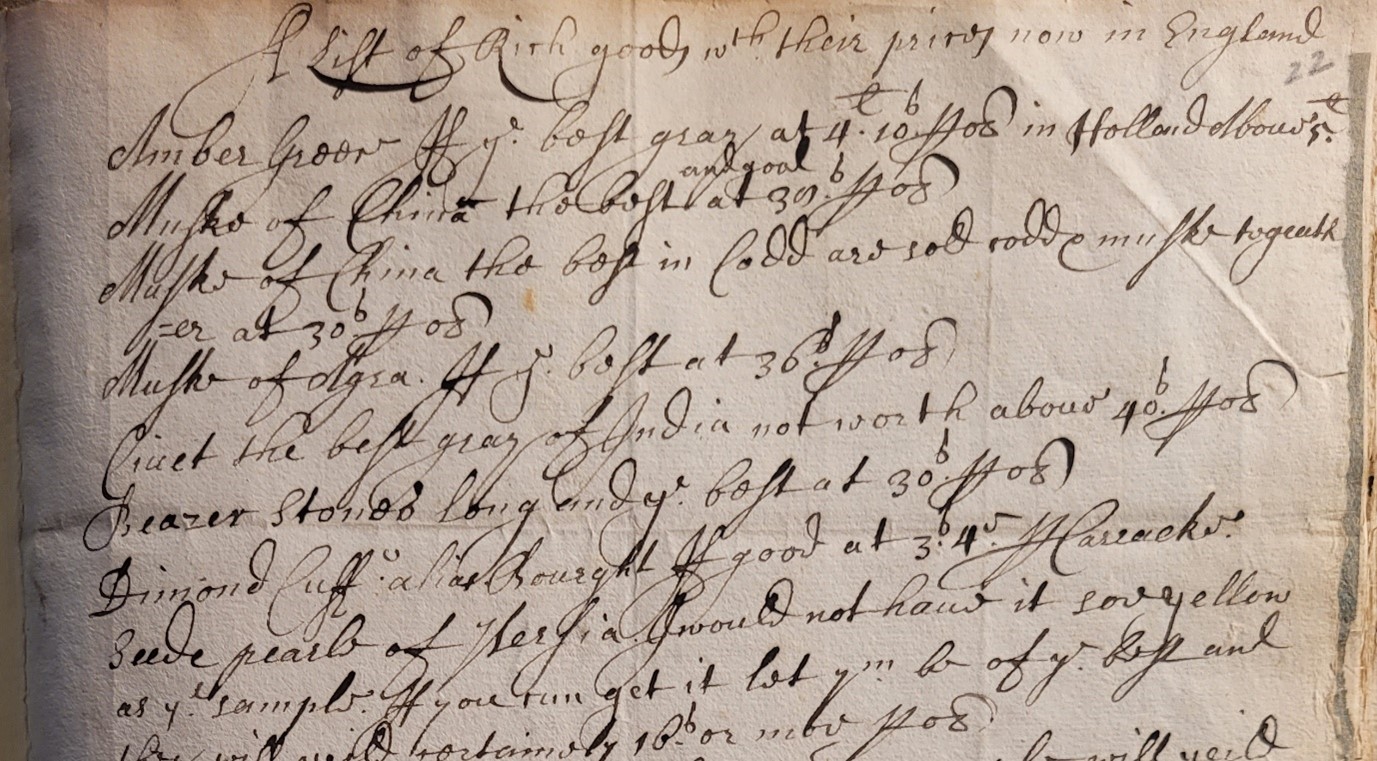

The papers of Nicholas Buckeridge – preserved in the Bodleian Library in Oxford – are primarily written manuscripts pertaining to his life as a merchant.[1] They are, more than anything else, a collection of lists, accounts, and descriptions of the goods Buckeridge sought to trade in while abroad, especially while resident in Bandar Abbas on the Persian Gulf. These letters – often written by his brother Edward rather than Nicholas himself – afford us valuable insights into how merchants in the mid-seventeenth century prioritised and assessed such goods. For instance, Buckeridge received and sought out advice on trading in ambergris – a solid, waxy, flammable substance produced in the digestive system of sperm whales and collected from coastlines – used to make perfumes and medicines); fresh rhubarb, which was native to Persia and used as a purgative; ‘China root’, which was employed both as an aphrodisiac and as a cure for its venereal consequences; and bezoar stones, otherworldly stones created in the stomachs of some herbivorous animals, thought to cure nervous disorders and as an antidote to some poisons. And, of course, with all of this, there remained the pursuit of spice: Nicholas traded in galangal, cardamom, turmeric, ginger, cloves, and many others. This connected Nicholas to a vast network of merchants across Asia, including Armenians in Isfahan, brahmins in Surat, and silk merchants in China.

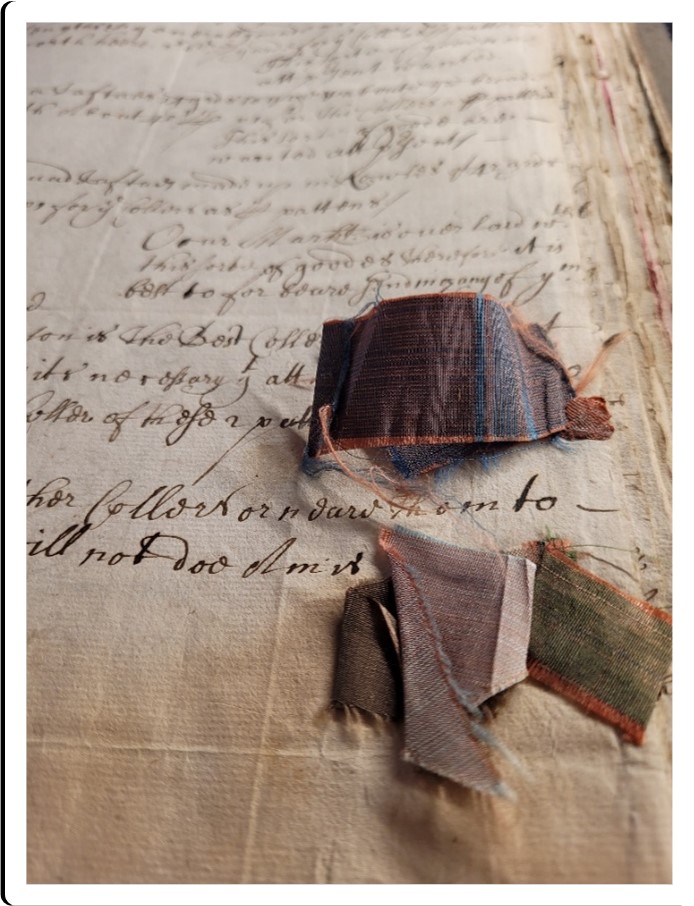

The photo at the beginning of his post, however, represents something different: simultaneously more tangible than these endless lists while also a startling reminder of the transient nature of much of the history we study.

The photo is of two pieces of taffeta, attached with melted wax to folio 29 recto of the Buckeridge papers, in a letter entitled ‘Directions for the buying of India taffetas’. It is a letter from Edward to Nicholas, where he advises his brother of what was, at that moment of writing, profitable in London for those trading in cloth such as this. This became a pattern in the brothers’ correspondence: Edward would take a snapshot of the London textile fashions and note the colours then in demand, the patterns which were selling well, and the origins being asked for by the fashionable elite. As Edward explains in the letter, textiles from Agra in Uttar Pradesh ‘are at present wanted’ as well as those in China, whereas those from Ahmedabad, because they were being shipped overland rather than by sea, were best avoided. What he wanted most of all, though, were the colours represented by these samples: ‘a deepe blew and crimson is the best coller yt can be sent for England’, like ‘these 2 patternes’. These, if sent, ‘will not doe amis’.

Samples such as these are extremely rare, often kept behind the glass of museums. They are not often there to be touched or seen. Where manuscripts are there for historians to touch and turn, to carefully manipulate and interrogate, these samples seemed to me – in that moment of surprise – a sudden intrusion of the past for which I was unprepared. They added a heft to the letter unfamiliar to historians, like me, who are used to flipping through dozens of letters in the course of an archive visit. They felt like outsiders.

Why was this the case?

In thinking about this moment for my current research – a book-length cultural history of the early EIC – it occurred to me that this encounter in the archive was so jarring because of the way it suddenly collapsed the distance between my time and that of Nicholas Buckeridge. As Nicholas’s lists suggest, much of what the EIC traded in was ephemeral in nature: spices meant to be eaten; plants and novelties that would rot, shatter, or degrade. Here, in front of me, were the literal threads of this trade for me to touch and feel, just as Edward and Nicholas would have done in the course of planning their trade across thousands of miles.

There were further threads of history woven into these samples, too. As historians, we are always led to think about how the material in our archives ‘got there’. This was no exception. Nicholas Buckeridge’s papers survive in the Bodleian Library because his son, Bainbridge Buckeridge (born in 1668 and named for his mother’s family), collected his father’s papers after the latter’s death in 1688/89. Bainbridge himself noted in the bindings to the papers that he collected them ‘without any regard had to method or the order in which they were wrote’, but knew they were from his father’s time in ‘Gombroon, called Bender or Bender Abassi’. This wasn’t the first time he had collected his father’s remaining papers, either: in 1691, Bainbridge donated his father’s notebook from the 1640s about ‘Divers[e] Precious Stones & Drugs’ to St John’s College, Oxford. This, then, affords the tantalising possibility that not only Nicholas and Edward Buckeridge encountered these samples of cloth while engaging in global trade in the 1640s and 1650s, but that Nicholas’s son might have run these samples through his fingers decades later while assembling the vestiges of his deceased father’s remaining papers. The fact is, we cannot really know.

Emily Robinson writes in her article ‘Touching the Void’ that the archive is the place where historians ‘can literally touch the past, but in doing so are simultaneously made aware of its unreachability’, that ‘concrete presence conveys unfathomable absence’. This encounter in the Buckeridge papers is another such moment of simultaneity: across not only thousands of miles but hundreds of years, the touching of an object and the sudden sparking of imagination can both make the past more immediate for us and remind us of what we cannot know. Reckoning with what has survived and what has perished is both the great privilege and the real burden of historical research.

[1] Bodleian Library, MS Eng Hist C 63.

Bibliography

Nandini Das, Courting India (London, 2023)

John R Jenson (ed.), Journal and Letter Book of Nicholas Buckeridge, 1651-1654 (Minneapolis, 1973)

Emily Robinson, ‘Touching the Void: Affective History and the Impossible’, Rethinking History, 14.4 (2010)

Edmond Smith, Merchants: The Community that Shaped England’s Trade and Empire (New Haven, 2021)

David Veevers, The Origins of the British Empire in Asia, 1600-1750 (Cambridge, 2020)

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’

- Collaboration across the pond: uniting histories of religious toleration in the American Revolution and European Enlightenment