New Year, New Research

23 September 2024In his post, Dr Ian Rapley, Senior Lecturer in East Asian History at Cardiff, talks about the joys and the trepidations of starting a new research project.

The onset of autumn means a new school year, new pencil cases, blank notebooks ready to be filled, and for some, new research to be started – whether that be undergraduate dissertations, masters or doctoral research or, for more experienced academic staff, starting new books or articles. After many years working on the history of language in modern Japan, I’m one of those starting anew with a new idea and new project.

I’ve boxed up my old research materials, familiar sources and reference works, and filed them away, leaving me sat at my desk with a blank sheet of paper and a few ideas to pursue. Old, but familiar emotions have floated up that I’ve not felt since I was a doctoral student – exhilaration, but also nervousness. The potential of an unexplored subject is endless. I especially love the sense of creative possibility in the different ways I might explore and present my new research, but at the same time, there are doubts: what if it doesn’t pan out?

The topic that I’m going to be working on over the next year is a history of the board game of Go. Go is best known in the West for the moment in 2016 when Google Deep Mind’s AI AlphaGo finally beat human professionals for the first time. (For various reasons, Go is computationally more complex than Chess, despite simpler basic rules, and so took longer to crack). The game has a history of well over a thousand years of play in East Asia, but I am particularly interested in its history in twentieth-century Japan.

Between the start of the century and the Second World War, the game underwent radical changes both in terms of how it was organised and run institutionally and in how it was played on the board. The most striking moment was a time in the 1930s when two young players, Go Sei Gen and Kitani Minoru, revolutionised opening play, developing a style that was fast, ambitious, and challenging of old orthodoxies. Exploring this, and related events, offers me a chance to think in new ways about the history of Japan’s modernisation and its relationship to cultural traditions.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Beyond this. there are other themes that I have yet to get to grips with fully. For example, the highest quality white stones have historically been made of shell, but the clams from which they came have been harvested almost to extinction, so there is both environmental history and material culture to explore. Similarly, connecting the revolution in play in the 1930s to the twenty-first century AI boom may reveal something about human (and artificial) creativity. Thinking about all this, and aware that over the next month or two lots of students will be starting their own research projects, I thought I’d offer a few simple things to think about when starting off a new piece of research:

Point One: Enjoy it

This is the most important piece of advice. Research is a voyage of intellectual discovery, and although there will be highs and lows, try to always keep in mind the sense of excitement at chasing down leads, discovering new things, and developing your ideas.

Although I’m just getting started on my research now, I had a chance to do a first archival visit earlier this year, when I visited the Kyoto branch Japanese national library. Walking down the stairs into the reading room for the first time was exciting, but it was also a little nerve wracking – I’d had a bit of a chance to look into the catalogue, but this was the first time I could really explore what sources there were. What if I discovered nothing?

The National Diet Library. No photos in the reading room…

It’s a truth of archival research that, while you’ll probably not find everything you expect to find and some of what you find will turn out to be not as interesting or as useful as you hoped, you will find something if you persevere. The real skills are working out what to make of what you find, keeping track of what you have found (and where, in case you need to revisit), and prioritisation. The list of things to read will grow faster than your capacity to read it all, and so good research involves a lot of organisation. In my case I’ve found a surprising amount about Go in early modern Japan. That’s potentially fascinating, but for now it’s something to put to one side as I concentrate on the mid 20th century.

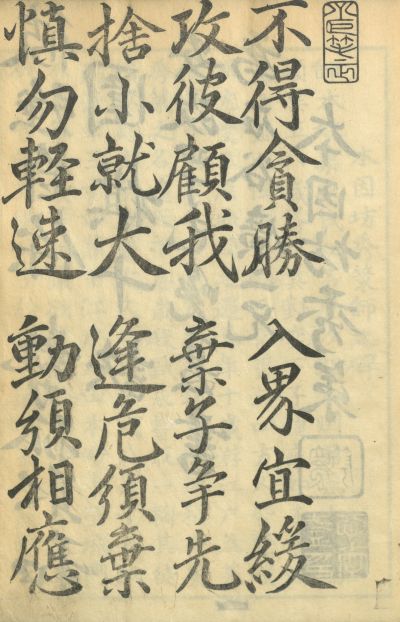

Some sources are easier to read than others.

Source: Japanese Go, Kaleidoscope of Books, National Diet Library (https://www.ndl.go.jp/kaleido/)

Point Two: Think about where your work fits in

There are different ways of thinking about a new project – some people suggest you have a research ‘question’ – something you’d like to know, or some existing debate on which you’d like to provide a new perspective. I have to confess I have a less sophisticated approach to identifying a topic. I’ve typically started with a subject that sounds interesting to me, and a faith that historical significance and meaning will emerge from digging into to it. So far, this approach has always born fruit, so fingers crossed.

That said, all research connects to work that’s gone before. Yes we’re generating new knowledge, but we do so best by building up from what has already been written.

This can take a variety of forms – taking methods applied in one field and transferring them elsewhere, re-examining known sources in the light of new insights or models, changing the time frame, or any number of other ways of thinking about your work in relation to what is already out there. However you do it, connecting your research to existing scholarship is one of the ways you turn antiquarianism (facts about the past) into real history (adding interpretation, insight, and meaning).

For my part, there is a growing body of work on boardgame studies on one hand and histories of other cultural traditions such as the tea ceremony or martial arts. My research is going to involve bringing these into contact with one another. There is also some scholarship on Go in the Japanese language (albeit most focusing on the early modern period), so I’ll be building on that as well.

Point Three: Make sure your project is the right size

My final piece of advice is to think about how much you’re biting off. Depending on what you’re doing, you may have a tightly defined timeline to work to. It is important to make sure that the scale of the research project matches the time and space you have to devote to it. It is very easy to pose questions that are fascinating but require a lifetime’s work to really answer. All of us, from undergraduate to professor, face deadlines of one form or another, but even if you have the luxury of time to do your research, at some point the research process has to come to a conclusion. It is important as a result to give a little thought about what you can reasonably do. That doesn’t mean that you can’t ask big questions, but it means that it is important to think about how to tackle them; for example for smaller projects, a case study based approach can be a good way of setting up a well-defined piece of research that nevertheless connects to big themes and questions.

One final thought: most historical research works towards a final written form – an article, a dissertation, a book, but there are also a lot of other ways that you can realise your research in addition to this. Presentations, posters, social media, digital resources, digital games, and more besides are all great opportunities for really creative and imaginative ways of presenting your work to a wider audience. For my part, I’m starting with the assumption that my research will take the form of a book, but I’ve been really inspired by works such as Anna Tsing’s The Mushroom At The End Of The World to think about how even as conventional a format as the academic monograph can be a space for innovation and creativity.

Whatever you’re working on, in whatever setting, I wish you all the best in the months to come.

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’

- Collaboration across the pond: uniting histories of religious toleration in the American Revolution and European Enlightenment