Fire, News and Slate: The Story of the ‘Hamburg Bluchers’

26 October 2023

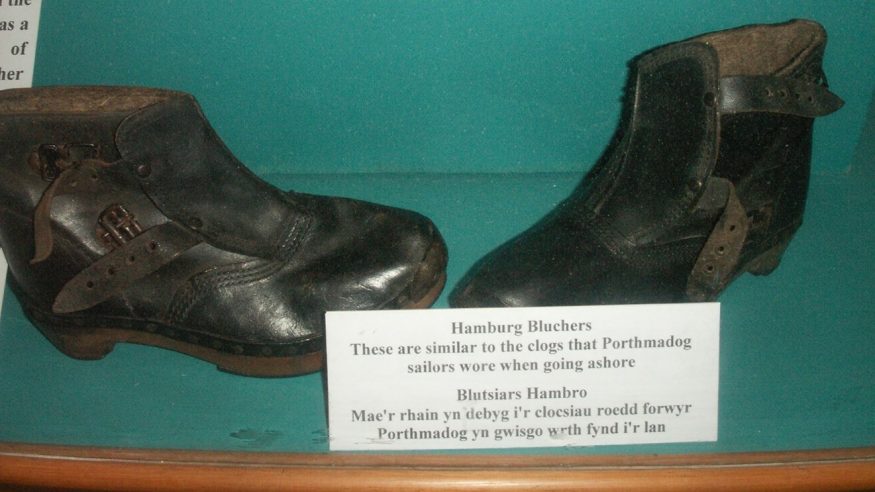

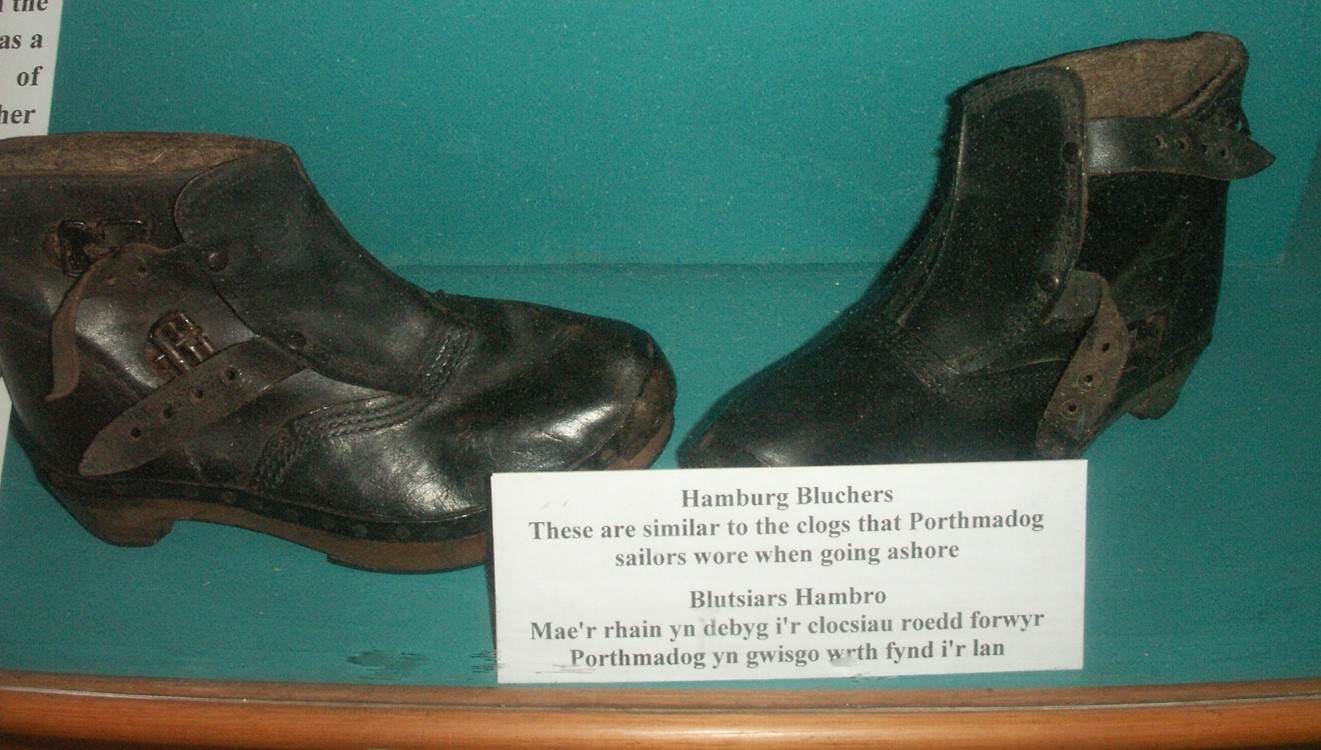

Porthmadog Museum in north Wales displays a pair of heavy work boots called ‘Blutsiars Hambro’ or ‘Hamburg Bluchers’, their heavy wooden soles matched with rough leather and metal buckles. The sign explains that they were ‘similar to the clogs that Porthmadog sailors wore when going ashore’. Fair enough, but what’s the story of the boot and its strange name?

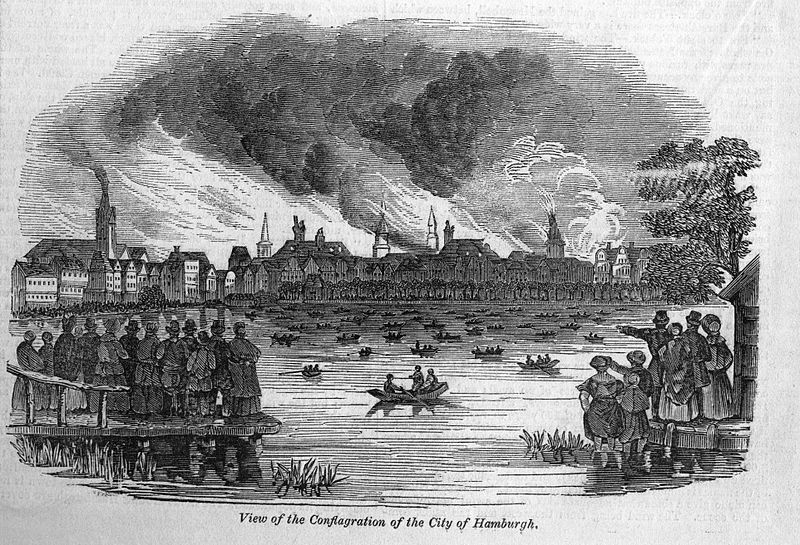

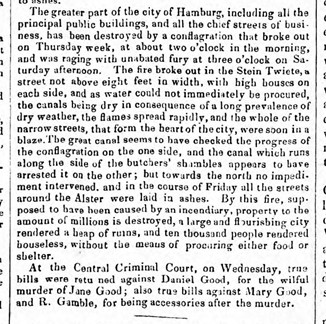

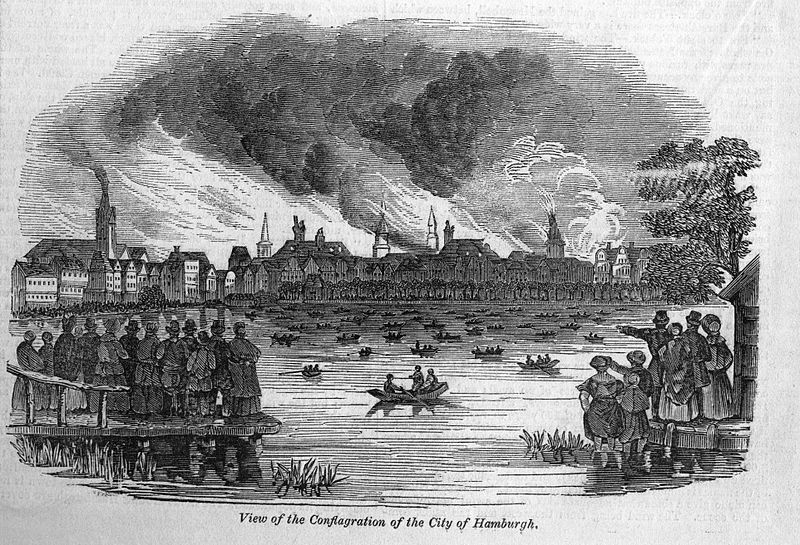

To explain, we are reaching back to the early 1840s. On 5 May 1842, a small factory in a narrow Hamburg lane was on fire, the strong winds blowing the sparks to the thatched roofs of adjoining houses and fanning the flames until the old quarter was all afire. The flames were so hot that they smelted the lead on church roofs, and by 8 May 1842, most of the 1,700 or so houses of Hamburg old town and its harbour had been destroyed, and over fifty people had died in the blaze.

By then, Europe was linked by a system of news and newspapers and the story, too, spread like wildfire. For the newly founded London Illustrated News a catastrophe of this dimension meant sales, and its very first number of 14 Mai 1842 featured a full report with illustrations.

Regional and local daily and weekly papers copied and reported the event as well, so that everybody who could read (and others who were told about the event) would soon have been familiar with the story. We cannot know what discussion went on in the Holland family, but Samuel Holland senior and junior, joint owners of the Rhiwbrydir slate quarry, soon made for Hamburg to convince the town elders that roofing townhouses with slate was the best way to avoid disasters of this dimension and that Welsh slate was the best in the world. Their visit rang in a period of close connections between the slate quarries and ports of north Wales, the city of Hamburg, and German railways. It was to last until the outbreak of the First World War.

Hamburg had to be rebuilt, but like most European countries at the time, Germany was also developing its railway system (like Poland and Ukraine, much of it with iron from the mighty Cyfarthfa and Dowlais ironworks in south Wales). The new stations and offices that dotted the railway routes also needed roofing, and here avoiding thatch was even more important. Steam trains were fired with coal, after all. The expansion of the Welsh slate quarrying and north-Walian ship-building industries in the second half of the nineteenth century are largely due to supplying that, slate for Hamburg and for German railway buildings. By 1875 more than 75% of north Welsh slate went to Germany. The main shipping route ran from Porthmadog, where the slates would be loaded, to Hamburg, from where they’d go on their way to their final destination.

Exporting goods and economic links lead to people moving and a host of other international connections. Ships built in north-Wales docks were soon named ‘Frau Minna Peterson’ or ‘Konsul Kästner’ after particularly good German customers and their wives. German seamen would start their life-long careers on Porthmadog ships, and Welsh dockers would unload the slate alongside their German mates in Hamburg. Towards the end of the century the Welsh presence there was so strong in Hamburg that according to Welsh maritime historian Aled Eames a shipping magnate even learnt Welsh:

At Hamburg the ship stores of the Marquard family were much patronised by Welsh seamen, who eventually made the Marquard warehouse their central meeting place, Caesar Marquard went out regularly to meet Welsh ships and learnt Welsh so well that the overlooker of the Liverpool ‘Cambrian’ ships claimed that Marquard ‘could speak Welsh like a native with a good Caernarvonshire accent’.

While some Germans picked up a different language, their Welsh counterparts liked their boots, the heavy ‘Blüchers’ devised for common soldiers during the Napoleonic Wars and named after the general who won the allied forces the final battle against Napoleon. On their return to Porthmadog, they’d wear these handy boots, the ‘Hambros’ of Hamburg, named after ‘Blutsiar’ – their rendering of ‘Blücher’.

Like so many other trade and friendly connection between Britain and Germany, these close links came to an end with the outbreak of war in 1914. Heart-rending stories tell of sweet-hearts prised apart in Hamburg, Welsh apprentices stuck on German ships, and Germans driven out as enemy aliens or interned on the Isle of Man. The slate industry never recovered after the war. However, the traces of this close connection can still be seen in the objects displayed in Welsh museums, and of course on top of many of the red-brick railway stations along the routes south from the North Sea to the remainder of Germany. ‘Marquard’ is still a Hamburg export company waiting to be researched by me.

Written by Dr Marion Loeffler is Reader in Welsh History and History at Cardiff University

If you want to know more about Dr Loeffler’s research, see Dr Marion Loeffler – People – Cardiff University

Ar Dân! Stori y ‘Blwtsiars Hambro’

Yn Amgueddfa Porthmadog, ceir pâr o sgidiau gwaith trwm o’r enw ‘Blwtsiars Hambro’ neu ‘Hamburg Bluchers’, esgidiau tebyg i glocsiau dawnsio gwerin trwm, â lledr weddol uchel gyda bwcl i’w gau. Mae’r arwydd yn esbonio bod nhw’n ‘debyg i’r clocsiau roedd morwyr Porthmadog yn gwisgo wrth fynd i’r lan’. Digon teg, ond o ble daethant a beth mae’r enw yn ei olgygu?

I esbonio, mae’n rhaid mynd yn ôl i’r 1840au cynnar. Ar 5 Mai 1842, dechreuodd tân mewn ffatri fach yn ninas Hamburg yng ngogledd yr Almaen a ledaenai’n gyflym, gwyntoedd cryfion yn chwythu’r gwreichion o un to gwellt i’r nesaf, o un tŷ i’r llall yn gyflym. Bu’r fflamau mor boeth eu bod yn toddi’r plwm ar do eglwysi’r ddinas. Erbyn 8 Mai, dinistriasid rhan fwyaf hen ddinas a phorthladd Hamburg, rhyw 1,700 o dai, a bu farw dros hanner cant o bobl.

Roedd system newyddion a phapurau newydd yn cysylltu Ewrop cyfan erbyn hyn, a’r London Illustrated News yn cychwyn, y rhifyn cyntaf yn ymddangos ar 14 Mai 1842 gydag adroddiad llawn a lluniau erchyll o’r galanas mawr. Yn ngogledd-orllewin Cymru, byddai’r sawl a fedrai darllen (a’r sawl byddai’n gwrando arnynt) yn cael yr holl stori echrydus i’w hystafelloedd byw yn Saesneg ac yn Gymraeg. Yn eu plith roedd perchnogion Chwarel Rhiwbrydir, Samuel Holland a’i fab. Gan weld cyfle arbennig, teithiant i Hamburg i hysbysebu arweinwyr y ddinas bod llechi yn ddeunydd llawer mwy diogel na gwellt, ac mai llechi o ogledd Gymru oedd y gorau yn y byd. A dyna sut dechreuodd cysylltiadau agos masnachol rhwng ardal llechi a phorthladdoedd gogledd Cymru a gogledd yr Almaen, a barhaodd tan y Rhyfel Byd Cyntaf.

Yn ogystal â gorfod ail-adeiladu Hamburg, roedd yr Almaen yn datblygu system o reilffyrdd, llawer ohono gydag haearn o Gyfarthfa a Dowlais yn ne Cymru. Byddai’r gorsafoedd rheilffordd angen to hefyd, a llechi oedd y dewis ar gyfer rhain i osgoi tân hap a damwain oddi ar y trenau ager. Amcangyfrir bod twf allforion llechi ail hanner y ganrif yn seiliedig ar y fasnach â’r Almaen, a bod dros 75% o lechi gogledd Cymru yn mynd yno erbyn 1875. Fel arfer byddai’r llongau llawn llechi yn hwylio o Borthmadog i Hamburg, a’r diwylliant adeiladau llongau a phorthladdoedd gogledd Cymru yn elwa a datblygu yn ogystal.

Mae masnachu, cludo nwyddau a mordwyo yn creu cysylltiadau rhwng pobl a chenhedloedd, ac felly y bu yn achos y llechi. Byddai llongau newydd yng ngogledd Cymru yn cael eu henwi yn ôl cwsmeriaid Almaeneg pwysig, megis ‘Frau Minna Peterson’ neu ‘Konsul Kästner’. Meddai Aled Eames fod llawer o fechgyn Almaeneg wedi cychwyn eu gyrfaoedd morwrol ar longau o Borthmadog ac wedi aros yno am flynyddoedd llawer, a’r si yn codi bod poblogaeth Porthmadog yn hanner-Almaeneg. Byddai prentisiaid o Gymru yn gweithio ym mhorthladd Hamburg ac ar longau Almaeneg yn ogystal. Wir, dywedir i gynifer o ddocwyr o Gymru weithio yn Hamburg, fel bod pennaeth cwmni cludo mwyaf y porthladd Caesar Marquard yn siarad Cymraeg yn rhugl ag acen ogleddol!

Ymddengys i weithwyr dociau gogledd yr Almaen wisgo sgidiau gwaith trwm o bren a lledr, a mabwysiadwyd y sgidiau gan y Cymry oedd yn dadlwytho’r llechi a nwyddau eraill ochr yn ochr â’u mêts Almaeneg. Pan ddychwelant i Borthmadog i ymofyn rhagor o lechi o’r chwareli, byddant yn gwisgo’r bŵts handi hwn. ‘Hambrôs’ oedd yr enw oherwydd eu bod yn dod o Hamburg, a ‘Blwtsiars’ neu ‘Bluchers’ am fod y gair Almaeneg ‘Blücher’ yn cyfeirio at esgid milwrol trwm a ddyfeisiwyd yn ystod Rhyfeloedd Napoleon.

Fel llawer o gysylltiadau eraill, daeth y cyfeillgarwch agos rhwng pobl gogledd Cymru a gogledd yr Almaen i ben ym 1914. Roedd y Cymry a fu’n byw a gweithio yn Hamburg yn dychwelyd adre ar hast, ac Almaenwyr Prydain yn cael eu hanfon i wersyll mawr ar Ynys Manaw. Ceir straeon am brentisiaid Cymreig yn sownd ar longau yn yr Almaen, a rhai torcalonnus o gariadon wedi eu gwahanu am byth. Ni adferwyd y diwydiant llechi na’r cysylltiadau agos wedi diwedd y Rhyfel Mawr, ond gwelir yr olion o hyd yn amgueddfeydd Cymru ac ar doeau adeiladau cyhoeddus yn yr Almaen, yn arwyddion o gysylltiadau rhyngwladol agos. Yn Hamburg, ceir o hyd cwmni allforio o’r enw ‘Marquard’, i’w ymchwilio gen i.

Os hoffech wybod mwy am ymchwil Dr Loeffler, gweler Dr Marion Loeffler – People – Cardiff University

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’

- Collaboration across the pond: uniting histories of religious toleration in the American Revolution and European Enlightenment